Abstract

Aims: Carotid artery stenting (CAS) has been suggested by some clinicians as an alternative to endarterectomy (CEA), especially in some specific subgroups of the population. The aim of this study is to evaluate the costs of these two procedures.

Methods and results: A review of costs was performed on all patients who underwent elective treatment of carotid artery stenosis between January and December 2006 (184 CAS vs 97 CEA). Clinical data had been prospectively gathered from both the CAS and the CEA groups, while financial data was obtained retrospectively to match hospital admissions with the generated charge from the hospital business office. In this series there was one major event in CEA and one transient ischaemic attacks (TIA) in CAS. One death procedure-related event occurred in CEA. The mean total cost associated with a single CEA was € 3,897.86, whereas the cost associated with CAS was € 3,806.66. It was apparent that the increasing costs involved in purchasing material for CAS, were balanced by the lower spending for hospital stay.

Conclusions: Costs for CAS and CEA are comparable. In our experience, the choice between CAS and CEA is based on the comorbidity of the patient, the type of the lesion and the preferences of the patient, without economic criteria being important.

Introduction

Stroke is a common condition and today represents the third most common cause of mortality in western countries1. A stenosis of the internal carotid artery may be responsible for 10% to 20% of all strokes or transient ischaemic attacks (TIA), conditions that are a source of increased costs in our society.

Specifically, in Italy today the National Health Service requires that treatments demonstrate that they offer an improved quality of life as well as life-expectancy, while showing that the practice is cost-effective within a range deemed acceptable to society.

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) is still the gold standard procedure for severe carotid stenosis, displacing optimal medical management alone2-7. However, during the last several years, the performance of carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) has been suggested by some clinicians as an alternative to CEA, especially in some specific subgroups of the population8-15.

Today we deal with patients who are increasingly better informed informed, thanks to the internet and television, patients who become interested on their own for a minimally invasive treatment, such as an endovascular approach which requires no incision that would leave the neck with an inevitable scar. As for medical specialists themselves, neurologists frequently cite cranial nerve injury as one reason for avoiding surgery (up to 50% of patients may suffer some degree of cranial nerve injury)16, not to mention the fact that CAS offers a shorter recovery time and diminished morbidity.

In the past it has been difficult to justify CAS on the basis of economic considerations17, and some concerns have arisen regarding the high cost of stents and neuroprotection devices which may inflate the overall procedural costs relative to a CEA18-20. The idea that cost consideration should influence the care of individual patients is foreign to many physicians, who were taught to select the best management independent of cost. Rapidly rising health care expenditures, however, have forced society in general and physicians in particular, to examine their practice in terms of cost-effectiveness.

The aim of this study was to compare the economic impact of CEA and CAS in a single vascular and endovascular surgery unit during the course of one year.

Methods

A review of cost was performed on all patients who underwent elective treatment of carotid artery stenosis between January and December of 2006 at the vascular and endovascular surgery unit of University of Siena. We performed all carotid procedures in an operative theatre: 182 successful CAS procedures (out of 184 attempted: 98.91% success rate) and 99 successful CEA (out of 97 attempted procedures: 100%; including two converted CAS). The two failed CAS were immediately converted to CEA at the same time, the costs of these two conversions were calculated into the CAS group based on intention-to-treat.

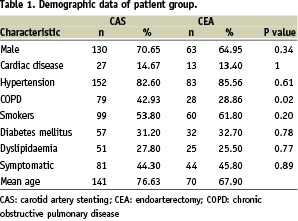

The demographic data and neurological history of the two study groups are summarised in Table 1.

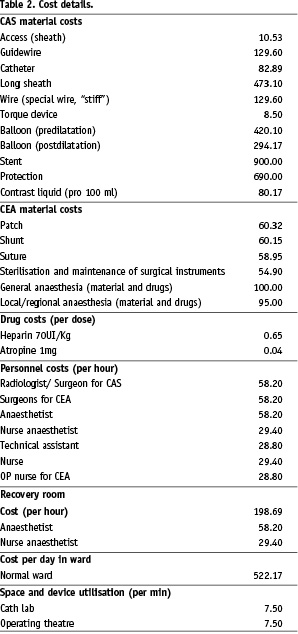

Demographic variables, clinical and intraoperative data were collected by the operative team in an apposite database, while financial data was obtained retrospectively to match hospital admission records based on the generated charge from the hospital business office. The hospital charges were then subsequently reviewed and categorised according to pertinent groups for these patients: CAS material costs, CEA material costs, drug costs (per dose), personnel costs (per hour), recovery room costs (per hour), in ward (per day) and space utilisation (per min).

A specific cost breakdown was also performed to determine the source of any cost disparities (Table 2).

In all CEA we consider the charge for sutures and ordinary maintenance and sterilisation of surgical instruments.

Recovery room was not useful for patients who underwent CAS, whereas the patients who were enrolled for CEA stayed routinely after procedure.

Written informed consent for intervention was obtained from all patients.

Data analysis included minor, major or fatal strokes and deaths (procedure-related, at discharge, at 30 days, and MI at 30 days. A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) was defined as a focal, retinal or hemispheric event from which the patient made a complete recovery within 24 hours. A minor stroke was defined as a new neurological deficit that either resolved completely between 14 and 30 days or increased on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale by < 3, an Italian prospective registry has adopted this definition, in order to allow for the stabilisation of ischaemic lesions before revascularisation*. A major stroke was defined as a new neurological deficit that persisted > 30 days and increased on the NIH Stroke Scale by > 4. A fatal stroke was defined as death attributed to an ischaemic stroke or intra-cerebral haemorrhagic stroke. MI was defined as new evidence of myocardial damage as indicated by elevation of either creatine kinase or CK-MB to more than two times the upper limit of normal and troponin T > 0.1 ng/mL, usually in the setting of chest pain or electrocardiogram changes.

Our indications for treatment were the presence of a symptomatic carotid-artery stenosis > 70% or an asymptomatic stenosis of at least 80%.

The decision to undertake CAS or CEA was made on the basis of patient preference and overall evaluation by the vascular surgeon. Initially, in our experience, we decided to treat only on the basis of historical indications to CAS according to the Veith Consensus21: 1) high risk patients with symptoms 2) recurrent stenosis 3) previous radical neck dissection or cervical irradiation 4) high bifurcation or extent of the carotid lesions 4) indication for CEA but patient unfit for surgery. In addition, the prevailing opinion (8 of the 12 present at the consensus conference) was that CAS was also justified in patients with indications for CEA in the presence of a contralateral internal carotid occlusion. Today we chose the best surgical treatment on the basis of patients comorbidities (so called “high risk”), plaque characteristics and fully informed patient preferences. At the moment CAS, in our opinion, is relatively contraindicated to the following categories of patients:

– Patients with floating thrombus in internal carotid artery or common carotid artery .

– Very young patients (< 50 years) if they are at standard risk for CEA (ASA < 2. Score of the American Society of Anaesthesiologists).

We had a therapeutical shift from CEA to CAS in the last year and CEA became less common treatment in our department. This was justified at first by the good results from the CAS procedure in the last few years.

Patient assessment, medical treatment and description of the CAS procedure have been previously published12. CEAs were performed using a standard medial approach and, usually, a longitudinal arteriotomy.

In CAS procedures the personnel involved were two surgeons, one anaesthetist and one nurse. In the CEA procedure the personnel involved were three surgeons, one anaesthetist, one nurse anaesthetist, one OP nurse and one nurse. The differences in terms of surgeons involved in CEA (3) and in CAS (2) are mainly due to the necessity of a correct vision of the operating field in the CEA group.

Statistical analysis

All results were analysed using SPSS statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). All values were expressed as mean±SD. The Fisher exact test was used to compare the rates between the two study groups (CEA vs CAS) for categorical variables, and all probability values were two-tailed, with a value of p<0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

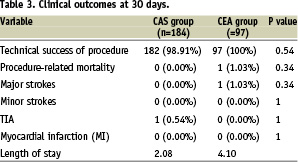

Technical success was achieved in all CEA and in 98.91% of CAS procedures, there was only one procedure related mortality in the CEA group and there was none in the CAS group (1.03% vs 0%, p=NS). This mortality was attributed to a fatal haemorrhagic stroke on the fifth post-operative day, after discharge.

The rate of major adverse events was one (1.03%) in the CEA group (a major stroke in – and probably due to – the presence of vulnerable plaque, to an embolisation during the exposure of the carotid bifurcation. The patient made a gradual improvement from the stroke and was discharged on the eight day after the surgical procedure) and zero in the CAS group (p=NS). There was only one case of TIA in the CAS group in a symptomatic patient (a retinal event from which made a complete recovery within 24 hours), and there was none in the CEA group (0.54% vs 0%, p=NS). In both groups, no MI was observed. Clinical outcomes at 30 days are illustrated in Table 3.

Patients who were enrolled for CEA stayed on average for 2.05 (1-3) hours in the recovery room, in our department we have a para-intensive care unit with continuous cardiopulmonary monitoring so the CEA patients are transferred to the recovery room only to monitor for early local complications like latero-cervical haematomas.

The average time for CAS was 31 minutes in operative theatre, and 85 minutes for CEA.

The average medium length of stay for the CAS group was 2.08 (2-7) days and for the CEA group 4.10 (4-9) days. About 70% of the CEA patients comes from remote regions, and the preference is to keep this patient in a protected environment in order to monitor for adverse events related to the surgical approach.

Concerning CAS material, we used in all procedures: One sheath (100%), one guidewire (100%), one special “stiff” wire (100%), one catheter (100%). For predilatation we used a balloon in two cases (1.09%), and in all cases we used a balloon for postdilatation (100%), one stent (99.45%), and one filter for neuroprotection (100%). One hundred ml of radiographic contrast agent was used for each procedure. In one case we used two stents in the same patient (0.55%).

In the CEA group, we performed general anaesthesia (GA) in 21 cases (21.2%) with the routine use of intraluminal shunting, a local-regional anaesthesia (LA) in 78 cases (78.8%) with selective shunting (9 cases - 11.53%), over-patching in 83 procedures (83.84%) and direct suture or eversion technique in 16 cases (16.16%). We observed no important differences between the LA and GA groups in terms of procedural costs or effectiveness of the treatment.

Our analysis of these two procedures produces the following results: the mean total cost associated with a single CEA was € 3,897.86, whereas the cost associated with CAS was € 3,806.66.

An analysis of the costs has also been carried out, allowing us to estimate how material expenditures compare to the cost of a longer hospital stay.

What has emerged is that the more increased costs involved in purchasing CAS materials (€ 2,323.52 vs € 278.70 for CEA) are balanced out when we take into account the lesser cost for hospitalisation necessitated by CAS (€ 1,044.34 for CAS vs € 2,088.68 for CEA).

Discussion

In the last few years, many in the scientific world have been studying CAS. The experience of many single centres has been collected, with revealing data about the efficacy of CAS, but only few randomised trials comparing CAS vs CEA have been published.

The Cochrane database22 reports a total of 1,269 patients with carotid artery stenosis that were treated in five different randomised trials (Leicester 2001, Wallstent 2001, Cavatas 2001, Kentucky 2001, Sapphire 2004). This database reports a heterogeneity of outcome, no significant difference in the major risks of treatment, and wide confidence intervals which indicate that it is not possible to see conclusive differences that favour one treatment over another. Currently, there is much interest in the results of on-going trials, and two of these, EVA-3S23 and SPACE24, have just published their data.

On the basis of this current evidence, CAS with cerebral protection, in the hands of an experienced operator, should be considered equal if not superior to CEA in high-risk patients. The major difficulty that needed to be justified today is whether this procedure costs more than CEA, which was a well proven technique for carotid bifurcation stenosis25.

Only a few studies have investigated the cost differences between the CEA and CAS. In contrast, three additional studies did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in cost, but these studies did not include the routine use of distal embolic protection devices26-28.

In the USA there are currently only two approved stents and three neuroprotection devices18, for this reason the costs of CAS compared with CEA are higher than in the EU, or specifically in Italy. And while older literature29 emphasises the clear difference in terms of expense between these two procedures, it is much to the disadvantage of the endovascular ones. This difference has now, fortunately, disappeared, reduced in the last few years by the steady introduction within Europe of new devices, creating a truly competitive marketplace, which has played a key role in lowering the prices of individual equipment and supplies. Moreover, the Italian National Health Service allows the use of only the least expensive devices, which has further lowered their cost.

From the analysis of existing data, it appears that CAS is not inferior to CEA in terms of clinical outcomes, and now the cost differences between the two procedures, traditional and endovascular, has been shown to not substantially modify the budget of a vascular surgery centre.

There are several limitations inherent, however, to this study. First, and foremost, is the non-randomisation of the patient selection. We believe though, that the efficacy of CAS techniques, allows for greater inclusion of surgically high-risk patients within the CAS group.

Conclusions

With the question of economic considerations here laid to rest, modern vascular surgeons have before them two absolutely effective techniques, each of which can be adapted to suit individual patient needs, confident in the knowledge that overall costs between these two procedures will be minimal.

From our experience, the choice between CAS and CEA is exclusively one based on the comorbidity of the patient, the type and the place of the lesion30 and the specific preferences of the patient, without considerations of an administrative, economic character.

We know that our outcome is difficult to compare with the results at other institutions – we are here merely explaining our own single centre experience. However, we hope that the diffusion of this study will allow others to reflect on the costs of endovascular procedures, rendering them more accessible for other institutions as well.

* “Plaque Stabilisation and the SUBMARINE results; Serum and Urinary plaque vulneraBility bioMARkers detectIoN before and after carotid stEnt implantation”, presented at the TCT, 2006 in Washington.