Abstract

Background: Comparative data of durable polymer (DP) versus biodegradable polymer (BP) drug-eluting stents (DES) are limited in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Aims: We sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of DP-DES and BP-DES in ACS patients receiving complex PCI.

Methods: This study was a post hoc analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial. ACS patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to DP-DES or BP-DES in the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial. Complex PCI was defined as having at least 1 of the following features: ≥3 stents implanted, ≥3 lesions treated, total stent length ≥60 mm, bifurcation PCI with 2 stents, left main PCI, or heavy calcification. Patient-oriented (POCO, a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and any repeat revascularisation) and device-oriented composite outcomes (DOCO, a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, or target lesion revascularisation) were evaluated at 12 months.

Results: Among 3,301 patients for whom full procedural data were available, 1,140 patients received complex PCI. Complex PCI was associated with higher risks of POCO and DOCO. The risks of POCO were comparable between DP-DES and BP-DES in both the complex (HR 0.87, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.57-1.33; p=0.522) and non-complex (HR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.56-1.24; p=0.368; p for interaction=0.884) PCI groups. DOCO was also not significantly different between DP-DES and BP-DES in both the complex (HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.43-1.27; p=0.278) and non-complex (HR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.38-1.19; p=0.175; p for interaction=0.814) PCI groups.

Conclusions: In ACS patients, DP-DES and BP-DES showed similar clinical outcomes irrespective of PCI complexity.

Introduction

Polymer technology is an important component that determines drug-eluting stent (DES) performance after implantation. Polymers used in the first-generation DES were associated with chronic inflammation and delayed endothelisation12, and thus, subsequent development has focused on biocompatible durable polymers and biodegradable polymers. Although biodegradable polymer DES (BP-DES) may seem, in theory, to be advantageous compared with durable polymer DES (DP-DES), previous studies reported comparable clinical outcomes between DP-DES and BP-DES, with both types of stents showing excellent efficacy and safety3456789. We also reported the results from a large-scale randomised trial that showed the non-inferiority of DP-DES with regard to patient-oriented outcomes in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients10. However, their comparative outcomes have not been thoroughly investigated in those receiving complex procedures. Therefore, we sought to investigate the safety and efficacy of the two polymer technologies in ACS patients undergoing complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods

Study design and study population

This analysis was not prespecified and was a post hoc analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS (Harmonizing Optimal Strategy for Treatment of coronary artery diseases – comparison of REDUCtion of prasugrEl dose or POLYmer TECHnology in ACS patients) trial. The HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial was an investigator-initiated, randomised, parallel-group, open-label, adjudicator-blinded, multicentre trial performed at 35 centres in the Republic of Korea and with a 2x2 factorial design testing two independent hypotheses. One explored the non-inferiority of the prasugrel dose de-escalation therapy after 1 month from the index PCI compared to the maintenance of a conventional dose of prasugrel in ACS patients, and the other evaluated the non-inferiority of DP-DES to BP-DES for patient-oriented clinical outcomes (POCO). As this trial included ACS patients, dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended for at least 1 year post-PCI. The trial design and main results have already been published101112. The current results are from a post hoc analysis of the stent randomisation arm. ACS patients with at least 1 culprit coronary artery lesion were eligible for the trial. After coronary angiography, patients aged 19 years or older were screened and randomised to receive DP-DES (PROMUS Premier, Boston Scientific; XIENCE Alpine, Abbott; Resolute Onyx, Medtronic; DESyne or DESyneX2, Elixir) or BP-DES (Biomatrix, Biomatrix Flex, Biosensors; Nobori, Ultimaster, Terumo; or Orsiro, Biotronik). Patients with hypersensitivity or a contraindication to heparin, aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor or contrast media, or had any major or active bleeding, childbearing potential, or a life expectancy of less than 1 year were excluded. Patients who were not expected to be compliant with the protocol were also excluded. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating centre and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Definition of complex PCI and outcomes

Complex PCI was defined as a high-risk procedure with at least 1 of the following features: ≥3 stents implanted, ≥3 lesions treated, bifurcation PCI with 2 stents, total stent length ≥60 mm, left main PCI, or heavy calcification131415161718192021. Heavy calcification was based on qualitative assessment. It was defined as vascular wall radiopacities noted during the cardiac cycle before contrast injection at the stenosed segments, where the stents were implanted, by independent technicians from each hospital who were trained in qualitative and quantitative coronary angioraphy analysis.1822. Clinical outcomes were also evaluated according to the individual features of complex PCI and the degree of PCI complexity, which was defined as the number of complex PCI features.

The primary outcome was a patient-oriented composite outcome (POCO) at 12 months. The POCO was a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), and any repeat revascularisation. The secondary outcome was a device-oriented composite outcome (DOCO) at 12 months, including cardiac death, target vessel MI, and target lesion revascularisation (TLR). The individual outcomes of the composite outcomes, stent thrombosis, target vessel revascularisation (TVR), and non-TVR were also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were described as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, according to the distributions of variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test, while continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Kaplan-Meier estimates were calculated to present the cumulative incidence of clinical outcomes at 12 months, and group differences were evaluated using the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the effect of PCI complexity on clinical outcomes. The following variables were included for adjustment: age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, stroke, ejection fraction, current smoking, and clinical diagnosis. The consistency of the polymer effects between complex and non-complex PCI was assessed with a formal interaction test using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat analysis. All p-values were 2-sided, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical package R, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline patient and lesion characteristics

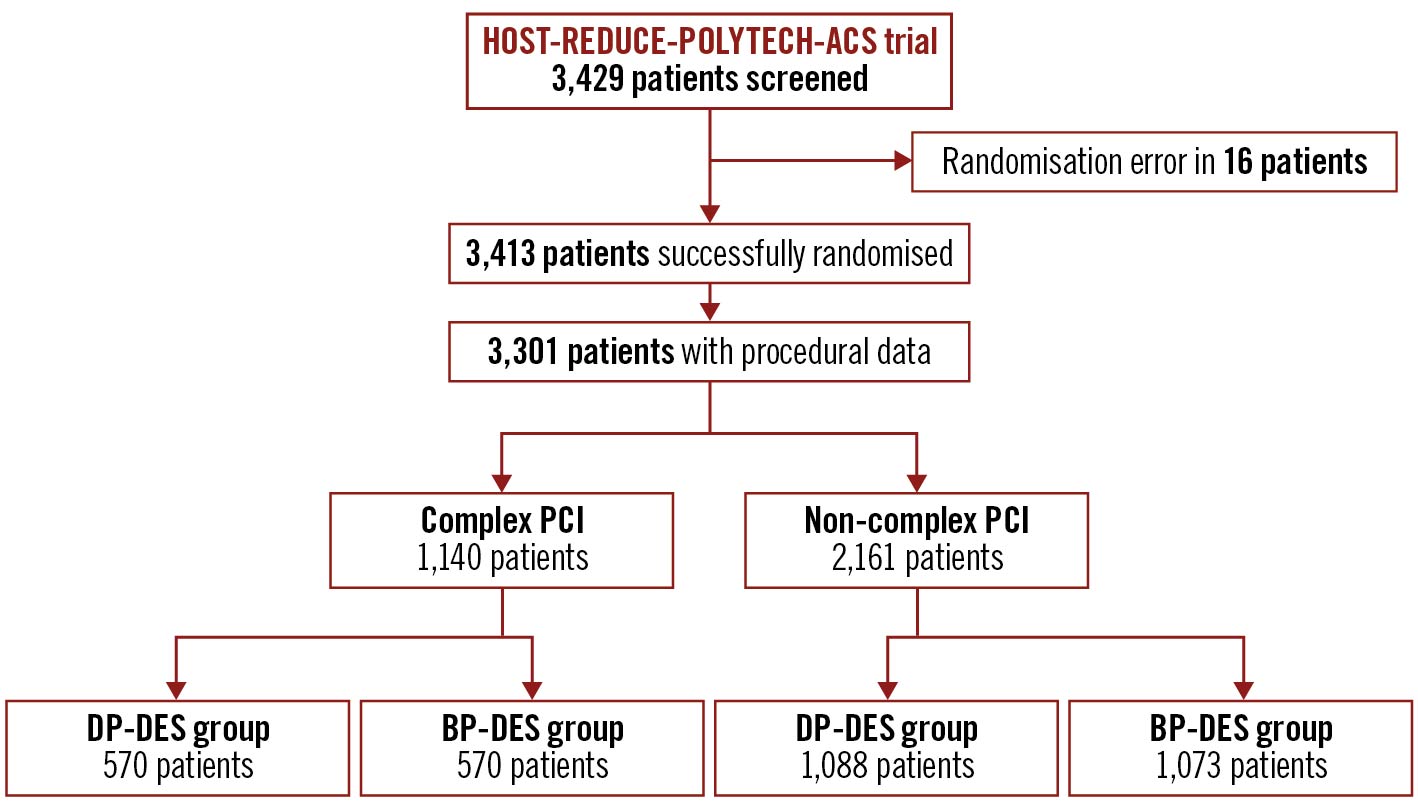

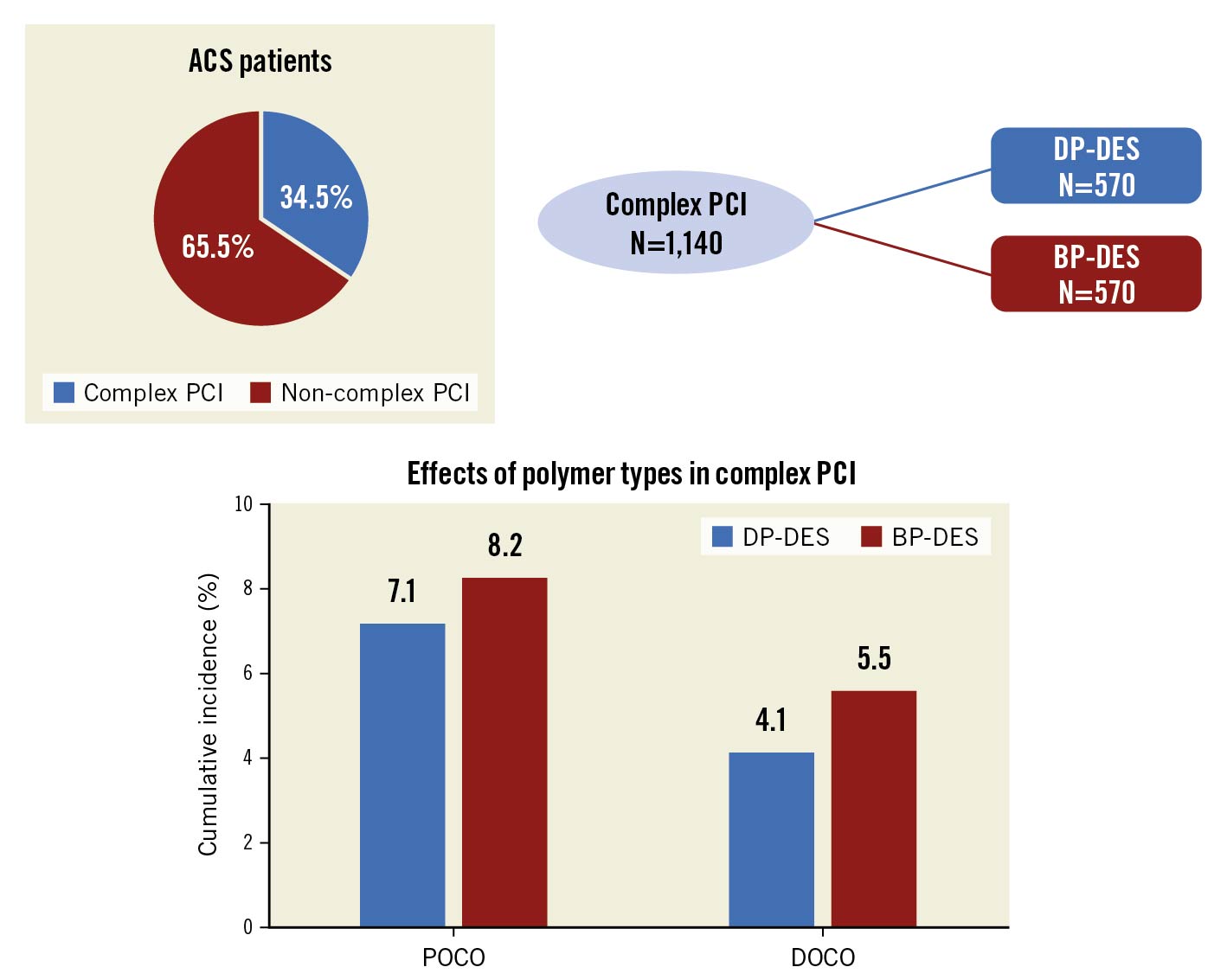

Among 3,413 ACS patients who were successfully randomised to receive DP-DES or BP-DES in the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial, complete procedural data were available in 3,301 patients and 72 patients were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). Based on the procedural data, patients were categorised into those who received complex PCI (1,140 patients, 34.5%) and those who received non-complex PCI (2,161 patients, 65.5%). Supplementary Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics between the complex and non-complex PCI groups. Among patients in the complex PCI group, 675 patients (59.2%) had a total stent length of 60 mm or longer, 518 patients (45.4%) had heavily calcified lesions, 514 patients (45.1%) had 3 or more stents, 259 patients (22.7%) had 3 or more lesions treated, 224 patients (19.6%) underwent bifurcation PCI with 2 stents, and 158 patients (13.9%) underwent left main PCI. Patients in the complex PCI group were older, more likely to present with unstable angina and had a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, stroke, and lower ejection fraction. The number of stents implanted was higher and intracoronary ultrasound was more often performed in those who received complex PCI.

Among patients in the complex PCI group, 570 patients (50.0%) were allocated to the DP-DES group and 570 patients (50.0%) to the BP-DES group (Figure 1, Table 1). In those who received non-complex PCI, 1,088 patients (50.3%) were assigned to the DP-DES group and 1,073 patients (49.7%) to the BP-DES group (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the 2 groups, except for family history of coronary artery disease in the complex PCI group (Table 1, Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1. Rates of BARC bleeding at 1 year after randomisation by prior CABG status and treatment arm. Kaplan-Meier curves with bleeding rates at 1 year of (A) BARC 2, 3 or 5 bleeding, and (B) BARC 3 or 5 bleeding for ticagrelor plus placebo versus ticagrelor plus aspirin in patients with and without prior CABG. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; Tica: ticagrelor

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of complex PCI patients.

| DP-DES (N=570) | BP-DES (N=570) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.6±11.3 | 64.6±11.0 | 0.998 | |

| Male | 447 (78.4%) | 431 (75.6%) | 0.291 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.6±3.2 | 24.7±3.3 | 0.829 | |

| Hypertension | 386 (67.7%) | 390 (68.5%) | 0.815 | |

| Diabetes | 292 (51.2%) | 276 (48.4%) | 0.374 | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 414 (72.6%) | 415 (72.8%) | 1.000 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 42 (7.4%) | 41 (7.2%) | 1.000 | |

| Peripheral vessel disease | 8 (1.4%) | 11 (1.9%) | 0.644 | |

| Never smoked | 306 (53.7%) | 313 (54.9%) | 0.114 | |

| Current smoker | 154 (27.0%) | 127 (22.3%) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 110 (19.3%) | 130 (22.8%) | ||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 21 (3.7%) | 23 (4.0%) | 0.878 | |

| Prior revascularisation | 72 (12.6%) | 83 (14.6%) | 0.388 | |

| Prior stroke | 46 (8.1%) | 46 (8.1%) | 1.000 | |

| Family history of CAD | 31 (5.4%) | 56 (9.8%) | 0.007 | |

| LVEF, % | 57.6±10.6 | 57.4±10.8 | 0.790 | |

| Presentations | STEMI | 55 (9.6%) | 55 (9.6%) | 0.998 |

| NSTEMI | 150 (26.3%) | 149 (26.1%) | ||

| Unstable angina | 365 (64.0%) | 366 (64.2%) | ||

| Treated vessel | Left main | 83/1,078 (7.7%) | 79/1,059 (7.5%) | 0.955 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 419/1,078 (38.9%) | 419/1,059 (39.6%) | ||

| Left circumflex artery | 243/1,078 (22.5%) | 244/1,059 (23.0%) | ||

| Right coronary artery | 333/1,078 (30.9%) | 317/1,059 (29.9%) | ||

| Lesion complexity | Heavy calcification | 253 (44.4%) | 265 (46.5%) | 0.513 |

| Bifurcation lesion | 116 (20.4%) | 108 (18.9%) | 0.602 | |

| Thrombotic lesion | 59 (10.4%) | 55 (9.6%) | 0.760 | |

| ACC/AHA Type B2/C lesion | 370 (65.0%) | 373 (65.4%) | 0.933 | |

| ISR lesion | 22 (3.9%) | 17 (3.0%) | 0.507 | |

| Multilesion intervention | 341 (59.8%) | 331 (58.1%) | 0.588 | |

| Left main PCI | 80 (14.0%) | 78 (13.7%) | 0.932 | |

| Treated lesion per person | 1.9±0.9 | 1.8±0.9 | 0.559 | |

| Stent number per person | 2.5±1.3 | 2.6±1.3 | 0.982 | |

| Total stent length, mm | 67.4±37.4 | 69.6±39.9 | 0.346 | |

| Stent thickness >100 µm | 0 (0.0%) | 198 (34.8%) | <0.001 | |

| IVUS use | 231 (40.5%) | 241 (42.3%) | 0.588 | |

| Medication at discharge | Aspirin | 554 (97.2%) | 552 (96.8%) | 0.862 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor* | ||||

| Clopidogrel | 178 (31.2%) | 172 (30.2%) | 0.748 | |

| Prasugrel | 334 (58.6%) | 322 (56.5%) | 0.510 | |

| Ticagrelor | 50 (8.8%) | 66 (11.6%) | 0.142 | |

| Beta blocker | 294 (52.1%) | 321 (56.9%) | 0.120 | |

| ACEi/ARB | 313 (55.6%) | 324 (57.4%) | 0.571 | |

| Calcium channel blocker | 146 (25.9%) | 138 (24.5%) | 0.631 | |

| Statin | 522 (92.6%) | 515 (91.3%) | 0.512 | |

| DAPT duration, days | 365 (85-365) | 365 (16-365) | 0.138 | |

| *DAPT was recommended to be maintained for one year. Values are mean with standard deviation or median with interquartile range. ACEi/ARB: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; BP: biodegradable polymer; CAD: coronary artery disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DES: drug-eluting stent; DP: durable polymer; ISR: in-stent restenosis; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction | ||||

PCI complexity and clinical outcomes

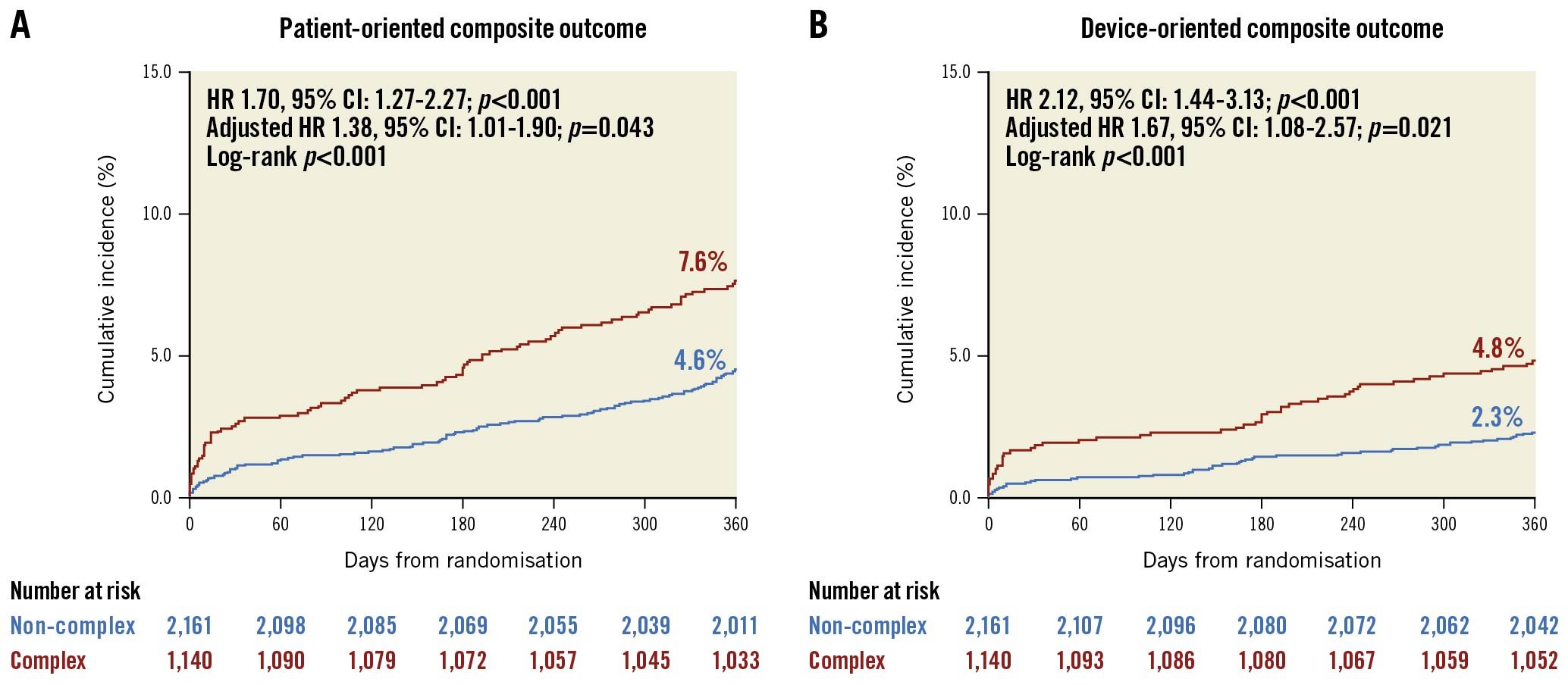

Patients who underwent complex PCI had a higher risk of POCO at 12 months compared to those who underwent non-complex PCI (7.6% vs 4.6%, HR 1.70, 95% CI: 1.27-2.27; p<0.001; adjusted HR 1.38, 95% CI: 1.01-1.90; p=0.043) (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3). These results were mainly driven by the increased risk of target vessel MI (adjusted HR 6.22, 95% CI: 1.33-29.04; p=0.020) and TVR (adjusted HR 1.94, 95% CI: 1.11-3.37; p=0.019) in the complex PCI group (Supplementary Table 3). The risk of DOCO at 12 months was also higher in the complex PCI group than in the non-complex PCI group (4.8% vs 2.3%, HR 2.12, 95% CI: 1.44-3.13; p<0.001; adjusted HR 1.67, 95% CI: 1.08-2.57; p=0.021), mainly driven by target vessel MI (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3).

The effects of complex PCI features on clinical outcomes are presented in Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4. All features showed an increasing trend for POCO and DOCO at 12 months. Among the individual complex PCI features, ≥3 stents implanted was associated with a significantly increased risk of POCO at 12 months, and ≥3 stents implanted, ≥3 lesions treated, and the total stent length ≥60 mm were associated with a significantly increased risk of DOCO at 12 months.

Figure 2. Bleeding events by prior CABG status at 1 year after randomisation. Forest plot illustrating outcomes of ticagrelor plus placebo versus ticagrelor plus aspirin according to prior CABG status. The interaction p-value is for the interaction test between randomised treatment assignment and prior CABG status. *Bleeding events were analysed in intention-to-treat cohort.ASA: aspirin; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CI: confidence interval; GUSTO: Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Arteries; HR: hazard ratio; ISTH: International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; Tica: ticagrelor; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TPA: tissue plasminogen activator

Polymer type and clinical outcomes according to PCI complexity

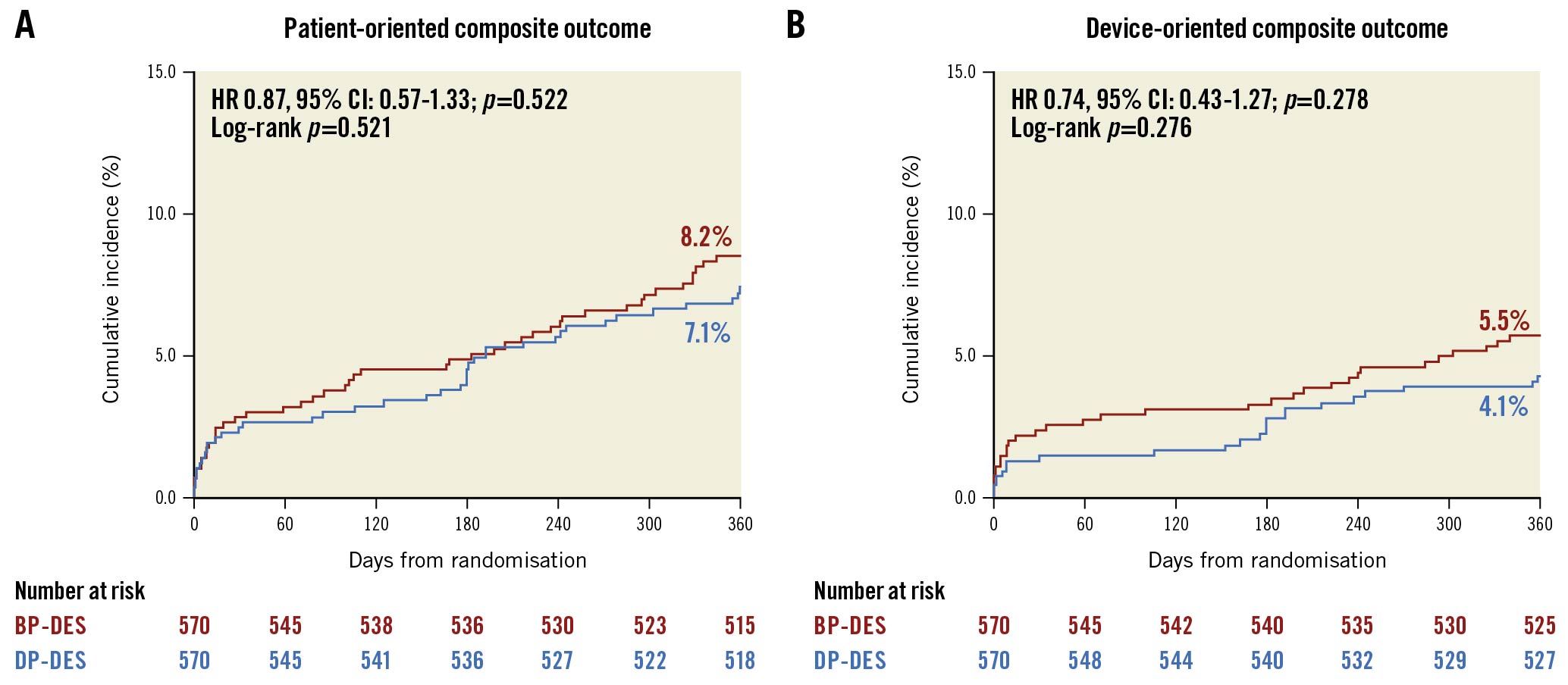

The outcomes according to the polymer type in the complex and non-complex PCI groups are presented in Figure 3, Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 2 . In the complex PCI group, there was no significant difference in the rates of POCO at 12 months between patients receiving DP-DES and BP-DES (7.1% vs 8.2%, HR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.57-1.33; p=0.522) (Figure 3, Table 2). The rates of DOCO at 12 months also did not significantly differ between patients receiving DP-DES and BP-DES (4.1% vs 5.5%, HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.43-1.27; p=0.278) (Figure 3, Table 2). The individual components of the clinical outcomes were also comparable between the 2 groups. These results were also consistent in the non-complex PCI group. The rates of POCO at 12 months were 4.2% in the DP-DES group and 5.0% in the BP-DES group (HR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.56-1.24; p=0.368) (Table 2, Supplementary Figure 2). The risks of DOCO at 12 months were also not significantly different between the 2 groups (HR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.38-1.19; p=0.175) (Table 2, Supplementary Figure 2). The effects of the polymer type on clinical outcomes were consistent in all clinical outcomes without significant interaction between complex and non-complex PCI (Table 2). Sensitivity analysis, excluding stents with thick struts, also showed similar results (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 3. Rates of all-cause death, MI or stroke, and cardiovascular death, MI or ischaemic stroke at 1 year after randomisation by prior CABG status and treatment arm. Kaplan-Meier curves with ischaemic rates at 1 year of (A) death, MI, or ischaemic stroke, and (B) cardiovascular death, MI, or ischaemic stroke for ticagrelor plus placebo versus ticagrelor plus aspirin in patients with and without prior CABG. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction; Tica: ticagrelor

Table 2. Clinical outcomes according to polymer types in complex and non-complex PCI.

| Complex PCI | Non-complex PCI | Interaction p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP-DES (N=570) | BP-DES (N=570) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | DP-DES (N=1,088) | BP-DES (N=1,073) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| POCO | 40 (7.1%) | 46 (8.2%) | 0.87 (0.57-1.33) | 0.522 | 45 (4.2%) | 53 (5.0%) | 0.83 (0.56-1.24) | 0.368 | 0.884 |

| DOCO | 23 (4.1%) | 31 (5.5%) | 0.74 (0.43-1.27) | 0.278 | 20 (1.9%) | 29 (2.8%) | 0.67 (0.38-1.19) | 0.175 | 0.814 |

| All-cause death | 20 (3.6%) | 25 (4.4%) | 0.80 (0.44-1.44) | 0.460 | 22 (2.1%) | 21 (2.0%) | 1.03 (0.57-1.87) | 0.928 | 0.561 |

| Cardiac death | 13 (2.3%) | 20 (3.6%) | 0.65 (0.32-1.31) | 0.229 | 14 (1.3%) | 14 (1.3%) | 0.98 (0.47-2.06) | 0.959 | 0.430 |

| Non-fatal MI | 6 (1.1%) | 8 (1.5%) | 0.75 (0.26-2.16) | 0.593 | 4 (0.4%) | 5 (0.5%) | 0.79 (0.21-2.93) | 0.722 | 0.955 |

| Target vessel MI | 5 (0.9%) | 6 (1.1%) | 0.83 (0.25-2.73) | 0.764 | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.2%) | NA | NA | 0.997 |

| Stent thrombosis | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (0.7%) | 0.25 (0.03-2.24) | 0.216 | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) | 0.49 (0.04-5.43) | 0.563 | 0.684 |

| Repeat revascularisation | 21 (3.9%) | 24 (4.4%) | 0.88 (0.49-1.57) | 0.658 | 26 (2.5%) | 31 (3.0%) | 0.82 (0.49-1.39) | 0.462 | 0.875 |

| TVR | 12 (2.2%) | 18 (3.3%) | 0.67 (0.32-1.38) | 0.275 | 8 (0.8%) | 18 (1.7%) | 0.43 (0.19-0.99) | 0.049 | 0.452 |

| TLR | 8 (1.5%) | 13 (2.4%) | 0.62 (0.26-1.48) | 0.280 | 7 (0.7%) | 15 (1.5%) | 0.46 (0.19-1.12) | 0.086 | 0.642 |

| Non-TVR | 11 (2.0%) | 9 (1.7%) | 1.23 (0.51-2.96) | 0.648 | 21 (2.0%) | 16 (1.6%) | 1.29 (0.67-2.48) | 0.440 | 0.928 |

| BP: biodegradable polymer; CI: confidence interval; DES: drug-eluting stent; DOCO: device-oriented composite outcome; DP: durable polymer; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; POCO: patient-oriented composite outcome; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVR: target vessel revascularisation | |||||||||

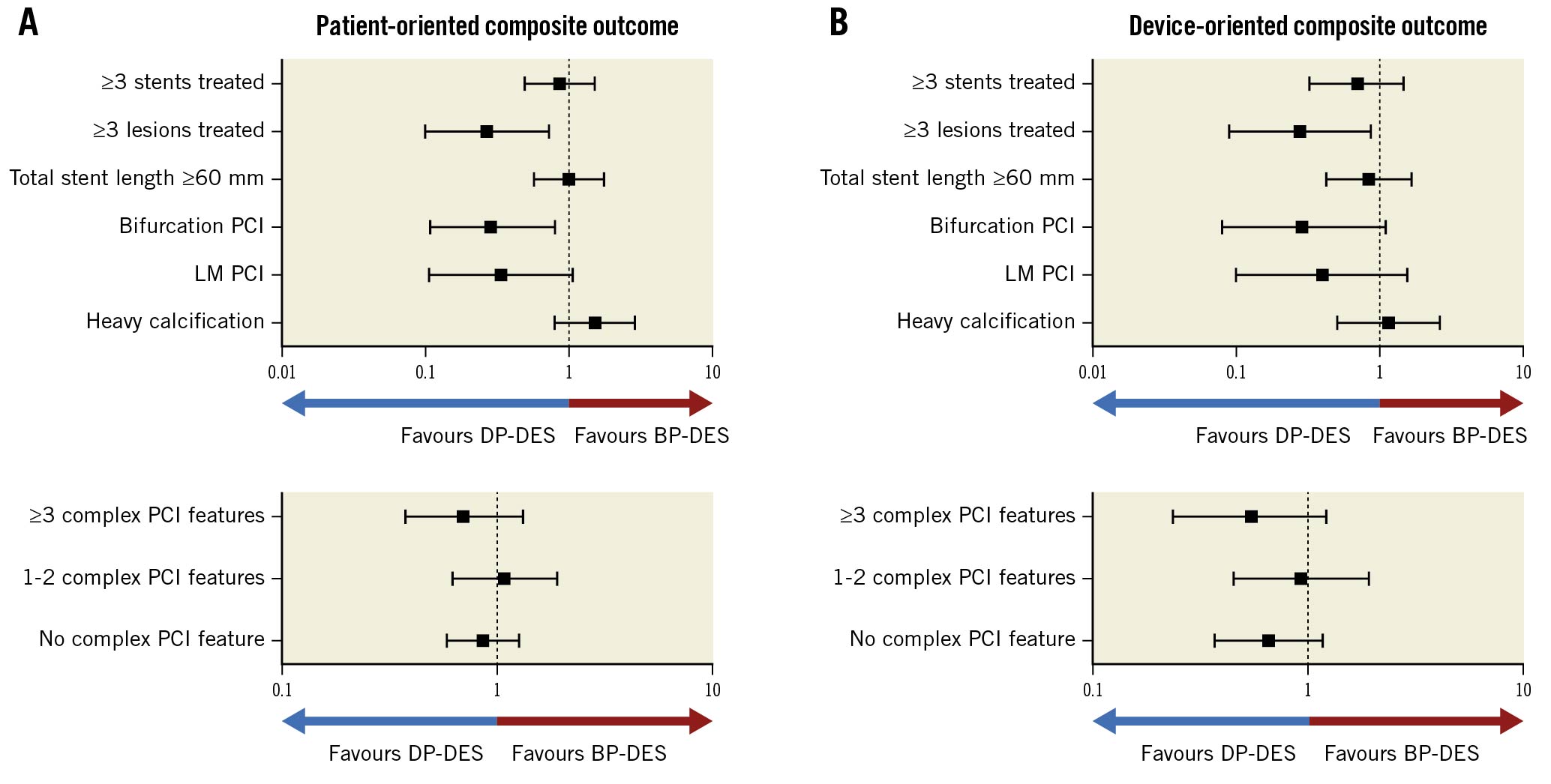

Effect of polymers according to type and degree of PCI complexity

Among the individual complex PCI features, DP-DES was associated with a trend toward better outcomes than BP-DES in patients with ≥3 lesions treated and bifurcation PCI with 2 stents, although the confidence intervals were wide (Figure 4, Supplementary Table 6). The number of complex PCI features was not associated with the risks of POCO or DOCO at 12 months (Figure 4, Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 4. Ischaemic events by prior CABG status at 1 year after randomisation. Forest plot illustrating outcomes of ticagrelor plus placebo versus ticagrelor plus aspirin according to prior CABG status. The interaction p-value is for the interaction test between randomised treatment assignment and prior CABG status. *Ischaemic events were analysed in per-protocol cohort. ASA: aspirin; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CI: confidence interval; CV: cardiovascular; HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction; ST: stent thrombosis; Tica: ticagrelor

Discussion

The current post hoc analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial is the first study that compared the efficacy and safety of DP-DES and BP-DES in ACS patients receiving complex PCI (Central Illustration). The principal findings were as follows: first, patients with complex PCI had higher risks of POCO and DOCO at 12 months. These results were mainly driven by target vessel MI and target vessel revascularisation. Second, the rates of POCO and DOCO at 12 months were comparable between DP-DES and BP-DES, irrespective of PCI complexity. Third, patients with ≥3 lesions treated and who underwent bifurcation PCI with 2 stents showed more favourable outcomes with DP-DES than BP-DES, but the confidence intervals were wide. The number of complex PCI features was not associated with the risks of clinical outcomes. These results suggest that both DP-DES and BP-DES have excellent clinical outcomes in complex PCI and non-complex PCI in ACS patients, but certain features of PCI complexity may be associated with better outcomes with DP-DES.

The HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial, in a 2x2 factorial design, evaluated the efficacy and safety of prasugrel dose de-escalation therapy and compared clinical outcomes between DP-DES and BP-DES in ACS patients1011. The main trial reported that prasugrel dose de-escalation therapy improved net adverse clinical events after ACS. We also reported that DP-DES were non-inferior to BP-DES regarding patient-oriented outcomes, and there was a decreased risk of device-oriented outcomes in the DP-DES group compared with the BP-DES group. However, whether such results are sustained in those receiving complex PCI has not been published previously. ACS patients have a heightened thrombotic milieu to begin with, and PCI complexity may complicate the thrombotic risk after PCI131415161718. Previously, we reported that even with the heightened thrombotic risk after complex PCI, prasugrel dose de-escalation therapy was not associated with an increased risk of ischaemic events but reduced the risk of bleeding events23. In the current study, complex PCI was associated with a 1.7-fold higher risk of POCO and a 2.1-fold higher risk of DOCO at 12 months of follow-up in ACS patients. These results were mainly driven by the increased risks of target vessel MI and target vessel revascularisation in the complex PCI group. Although patients in the complex PCI group were older and had more comorbidities, PCI complexity was still associated with increased risks of clinical outcomes even after adjustment for such factors. These different thrombotic risks in complex PCI in ACS patients might affect the efficacy and safety of DES according to different polymers. However, limited data are available for comparisons between DP-DES and BP-DES in such high thrombotic risk patients (ACS risk+complex PCI risk). Only 1 previous study reported comparable results between DP-DES and BP-DES after complex PCI24. However, the previous study was not based on dedicated ACS patients, and the results were based on an observational registry and not randomised data.

The current post hoc analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial demonstrated consistent results with those of the main trial. DP-DES and BP-DES had comparable risks of POCO at 12 months in both the complex PCI and non-complex PCI subgroups without significant interactions with PCI complexity. The risk of DOCO at 12 months was not significantly different between the DP-DES group and the BP-DES group in both the complex and non-complex PCI subgroups. Looking more closely, however, the device-oriented outcomes were numerically lower, although statistically insignificant in the DP-DES group in both the complex and non-complex PCI subgroups. In the main trial, the DP-DES group had a lower rate of DOCO at 12 months than the BP-DES group (2.6% vs 3.9%, HR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.46-0.98; p=0.038). Furthermore, DP-DES showed a trend toward favourable outcomes in patients with ≥3 lesions treated and those who underwent bifurcation PCI with 2 stents, although the confidence intervals were wide. These results suggest that there are no significant differences in clinical performance between the 2 stent types, but if there were any, device-oriented outcomes may favour DP-DES, even in complex PCI.

There may be several explanations for why the device-oriented outcomes were numerically lower in the DP-DES group. First, the stent strut thickness of early-generation BP-DES in the current study could have affected the results. A thick stent strut is associated with delayed endothelisation and thrombogenicity due to areas of blood recirculation and low shear stress, which may be more influential in complex PCI252627. As the current study included BP-DES with thick stent struts (more than 100 μm), this may have tipped the balance towards DP-DES. However, when we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the thick strut stents, the results were the same. A second possible explanation could be the excellent antithrombogenicity of the fluoropolymer and the BioLinx (Medtronic) polymer used in the contemporary DP-DES12. Ex vivo shunt studies reported lower thrombogenicity of fluoropolymer compared to other polymers used in BP-DES2829. Third, the polymer coating design can also affect the results. Most BP-DES have an abluminal polymer coating design. Abluminally coated DES have advantages in faster endothelisation. However, bare metal struts at the luminal area are also associated with a higher thrombogenicity compared to circumferentially coated polymer DES, and this effect can be more potentiated in complex PCI1.

Interestingly, the number of complex PCI features, reflecting the degree of PCI complexity, was not associated with any differences in clinical outcomes between DP-DES and BP-DES, while DP-DES showed a trend toward better outcomes in patients with ≥3 lesions treated and in those who underwent bifurcation PCI with 2 stents. We can infer that not all complex PCI features are associated with outcome differences between DP-DES and BP-DES. Although the overall efficacy and safety of DP-DES and BP-DES are very much comparable and excellent in ACS patients receiving complex PCI, our results suggest that there can be certain specific procedural features that may favour the use of DP-DES. Further studies, including long-term outcomes, are warranted to confirm this observation.

Central Illustration. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin after PCI in patients with a previous CABG surgery. Prior CABG patients who were event-free after 3 months after PCI with DES and adherent to DAPT with ticagrelor were randomised to ticagrelor plus placebo or ticagrelor plus aspirin. At 12 months after randomisation, prior CABG patients suffered significantly more bleeding and ischaemic events. However, patients receiving ticagrelor monotherapy, compared with ticagrelor plus aspirin, significantly reduced clinically relevant Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding outcomes without increasing ischaemic events of all-cause death, MI, or stroke. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CI: confidence interval; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DES: drug-eluting stent(s); HR: hazard ratio; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Limitations

There are several limitations to be considered in the current study. First, this was a post hoc analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial, and thus, there is a possibility of a type 1 error. The current findings should only be considered as hypothesis-generating. Second, this analysis was not prespecified, and PCI complexity was not stratified during randomisation. Therefore, both complex and non-complex PCI groups were not powered to give conclusive results between DP-DES and BP-DES. However, the findings from the current analysis were largely consistent with the previous overall trial results. Third, the current study was performed in a dedicated Asian population. As the risk of thrombogenicity and P2Y12 inhibition may be different between Asians and non-Asians, the study results should not be extrapolated to other ethnicities30. Fourth, the randomisation was only based on polymer type. Therefore, various other factors that contribute to the clinical performance of the stent, including stent design, strut thickness, antiproliferative drug, and its release kinetics, could be potential confounders. Fifth, as the presence of heavy calcification was based on visual estimation from coronary angiography, this could be a source of bias due to the low sensitivity and high interobserver variability of calcium. However, the assessment was performed by independent technicians trained in qualitative and quantitative coronary angiographic analysis, and we tried to minimise such risk by using a standardised definition. Sixth, the utilisation of intracoronary imaging during complex PCI was relatively low. Finally, the current study was based on 12 months of follow-up. Therefore, this study does not provide insight into the longer-term results of the different polymer technologies.

Conclusions

In patients with ACS, PCI complexity was associated with an increased risk of patient- and device-oriented outcomes, and DP-DES and BP-DES showed similar outcomes irrespective of PCI complexity. Our results suggest that current-age polymer technology, whether durable but biocompatible or biodegradable, shows excellent efficacy and safety with similar outcomes between the two technologies regardless of PCI complexity. Further randomised data are necessary to confirm these findings.

Impact on daily practice

The current post hoc analysis of the HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS trial is the first study to report outcomes of DP-DES vs BP-DES in ACS patients receiving complex PCI. Although patient-oriented and device-oriented outcomes were worse in patients with ACS receiving complex PCI, DP-DES and BP-DES showed comparable patient-oriented outcomes irrespective of PCI complexity. However, the trend of a lower risk of device-oriented outcomes in the DP-DES group was maintained irrespective of PCI complexity, like in the main trial, and some features of PCI complexity may be associated with slightly favourable outcomes with DP-DES.

Funding

This research was supported by Daiichi Sankyo, Boston Scientific, Terumo, Biotronik, Qualitech Korea, and Dio; and it was partially supported by a grant from Seoul National University Hospital (Research ID: 30-2021-0030). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02193971.

Conflict of interest statement

H-S. Kim has received research grants or speaker's fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Boston Scientific, Terumo, Biotronik, and Dio, as well as Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Edwards Lifesciences, Amgen, and Boehringer Ingelheim. B-K. Koo has received institutional research grants from Abbott Vascular and Philips. K. W. Park reports speaker’s fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Pfizer, InnoN Pharmaceutical, DaeWoong Pharmaceutical, and JW Pharmaceutical, outside of the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to the submitted work.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.