Introduction

The purpose of this article is to propose a checklist of key steps to follow during percutaneous coronary intervention in order to minimise human error and to prevent complications. The concept is derived from checklist airline pilots use to minimise the risk of accidents. This check list could later also serve as a scientific tool to determine the importance of each of these steps. Many steps of the checklist are deliberately not detailed in this article because they depend on institutional policy, for instance antithrombotic therapy, or local legislation. Several of these topics are in fact addressed by other articles in this journal. The idea is to help each institution create their proper list, that is kept with the patient and in which each step should be followed, filling out information or ticking – checking – a preset box.

A separate checklist could be proposed for the non-emergent procedures, these are elective PCI’s in patients in whom the coronary anatomy is already known; or “ad hoc” procedures. Another checklist would be used in case of emergent procedures. “Ad hoc” procedures should be avoided in a number of cases, depending on patient characteristics such as renal failure, severe heart failure or issues concerning patient information and consent. Lesion characteristics such as left main disease, chronic total occlusions, complex or diffuse lesions, the lack of proof of ischaemia and the impossibility to identify the ischaemia or symptom related lesion should also lead operators to consider elective PCI.

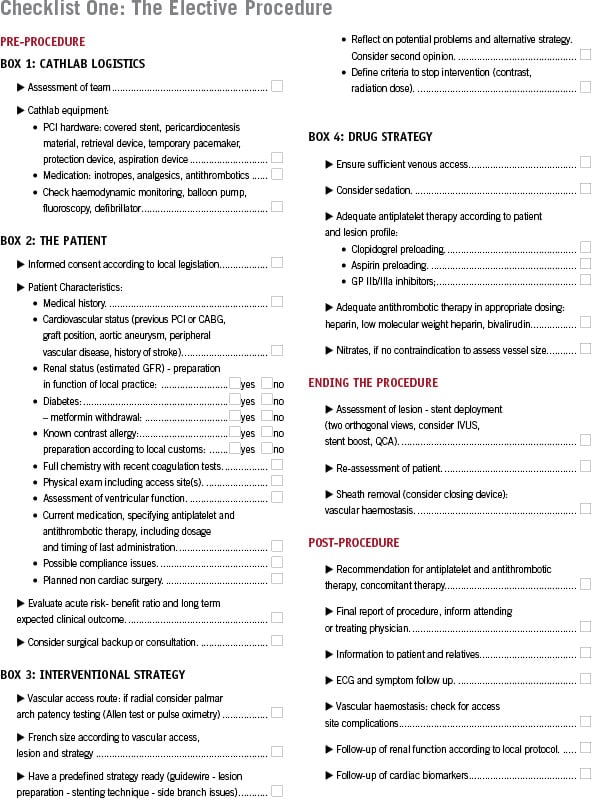

Elective procedures

The pre-procedure part of the check list deals with cathlab logistics, patient characteristics and interventional and drug strategy. Assessment of a team can include the availability of more experienced operators, as well as sufficient and competent nursing and technical staffs. The cathlab equipment box deals with the availability and functionality of tools necessary for complication management. The patient box includes several patient characteristics that help in evaluating the risk benefit ratio of the procedure and the impact on clinical outcome, which in turn is needed for informed consent (the form of which can depend on local legislation) and may lead to the need for surgical consultation or backup. We recommend filling in crucial lab values such as renal function and coagulation tests as well as specifying medication such as antithrombotics in the list, with dosing and timing of last dose if appropriate. Possible problems with compliance or planned non-cardiac surgery may influence the choice between drug-eluting or bare-metal stents. Defining stopping criteria in relation to contrast or radiation dose can especially be useful in treating chronic occlusions. A new concept of a practical radiation exposure clinical management score (RCME) was already suggested and elaborated by Locca et al.1

It is not possible to follow a checklist while performing the procedure. However, a big part of the complications do happen in this phase and one should always consider and reconsider the basic principles of PCI, as a mental checklist. This begins with correct vascular access, proper alignment of guiding catheter and curve selection. To avoid distal perforations, one should keep control of the distal wire at all times (keeping your eyes on the ball). It includes reassessing the need for further preparation of the lesion (predilatation, rotablation) or postdilatation. In case of a failed strategy or complications, the second opinion of a colleague can also be very helpful. During the intervention it is necessary to keep checking patient symptoms, blood pressure, saturation and ECG as well as keeping constant track of contrast usage (contrast countdown) and radiation dose to be able to stop the procedure if predefined criteria are met. The procedure will be ended if a satisfactory result is obtained, again re-evaluating the patient and proceeding, if possible, with sheath withdrawal and haemostasis.

Post-procedure follow-up should include patient and colleague information, recommendations on medical therapy and organised follow-up of renal function, access site, ECG and cardiac biomarkers.

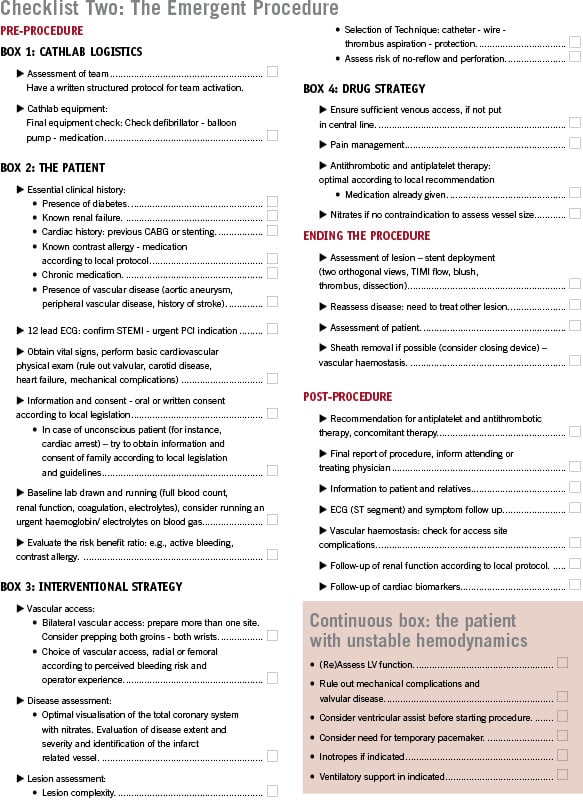

Emergent procedures

The checklist for an emergent procedure should include roughly the same steps as an non-emergent procedure. However, due to time shortage and sometimes lack of information, some steps can be simplified. Frequently full lab tests are not available while performing primary PCI. In case of suspected bleeding or electrolyte imbalances, a blood gas analysis can, however, provide useful information. At the same time there are other steps that are quite specific for the emergent procedure, such as the need for bilateral vascular access preparation or reflection on the need for thrombus aspiration. Clinical follow-up of the patient – with stabilisation of the haemodynamically unstable patient – is a constant obligation during emergent PCI. It is advisable to start with a complete visualisation with nitrate(s) of the coronary system to assess disease severity instead of concentrating immediately on the (presumed) culprit lesion. Assessing the risk of perforation should include the use of Gp IIbIIIa inhibitors and can lead the operator to avoid hydrophilic wires. Finally, the operator will be more often confronted with the problem of no-reflow than in a non-emergent procedures, which is dealt with in detail in this journal, and he or she will have to decide if the patient would benefit from the treatment of other, non-culprit lesions.

Conclusion

Some steps in this proposed checklist might seem trivial or simply logical. However, not following these steps can lead to complications. A physical checklist might prevent “cutting corners” or experiencing problems related to misunderstandings or bad communication between members of the PCI team, and thus help to prevent complications. As we already mentioned above, this checklist is not a cookbook list, but is “in construction” and should be further concretized by an individual institution according to its own policy and legislation.

Reference