Abstract

Management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in India essentially rests on the established reperfusion strategies with unique adaptations compelled by the socioeconomic structure of the country. Due to limited availability of trained interventionists coupled with financial limitations, thrombolysis remains the most utilised reperfusion therapy for AMI. Patient education through the active participation of physicians concerning the early detection of symptoms suggestive of AMI can enhance the impact of thrombolysis on the outcomes by narrowing the door-to-needle time. This article discusses some of these unique issues and possible solutions in the emerging economies to optimise outcomes in AMI.

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the most devastating presentations of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. With the rising incidence of diabetes and hypertension, the population of India is exposed to a significant risk of AMI. The medical system in India is likely to be overburdened with an increasing number of cases of coronary artery disease, one third of which will be presenting as AMI. Currently the exact figures of people suffering from AMI in India every year are lacking. The treatment strategies applied to patients presenting in India remain the same as the standard evidence-based therapies given by ACC/AHA and ESC1-3. However, the medical system in India poses significant challenges in applying of these strategies. The medical system in India largely comprises private hospitals which include small nursing homes, larger hospitals run by individual specialists, and corporate hospitals. Government institutions are available in most of the cities but are generally used by underprivileged patients. The percentage of people with medical insurance is relatively small and hence most patients are paying from their own pockets for the medical facilities they use.

Management of AMI – Indian scenario

The AMI management scenario in India has been documented in very few studies. The largest comprehensive data come from the CREATE registry4 and the recently presented Kerala ACS registry5,6. The CREATE registry studied more than 20,000 patients presenting with AMI to 89 hospitals in 50 cities of India spread across 10 regions. During the four-year period ending in 2005, the registry collected data on 20,937 patients presenting to 40 teaching and 40 non-teaching hospitals, out of which 41 hospitals were equipped with a catheterisation laboratory. The registry noted that, of the total number of patients, 60.6% patients presented with STEMI and 39.4% with non-STEMI. The patients presenting with STEMI presented to hospital about an hour earlier than those with non-STEMI with median time to presentation being five hours. However, only two fifths of these presented within four hours of symptom onset and almost one third presented after 12 hours. About 60% of patients received thrombolysis and median time for thrombolysis was 50 minutes. Only a minority of patients (8%) was subjected to PTCA during hospitalisation or the first 30 days, and 1.9% underwent bypass surgery. The 30-day mortality reported for STEMI in the registry was 8.6% with 0.7% patients developing stroke and 0.3% patients needing blood transfusions. Treatment analysis according to socioeconomic strata showed that, although antiplatelets were prescribed to practically everyone, other evidence-based therapy was significantly underutilised in lower socioeconomic strata. The mortality analysis based on socioeconomic strata showed a significantly lower mortality in the higher income group at 30 days as compared to the lower socioeconomic group. This difference disappeared after adjusting the treatment difference and treatment-related factors. The registry also reports very interesting observations on other aspects of management. Only 5.5% patients of STEMI used an ambulance service to reach hospital, whereas 84% of them reached hospital using a taxi or private transport, and one tenth actually used public transport to reach hospital. Similarly, observations on modes of payment are very interesting. Seventy-four per cent of patients paid from their own pockets for the treatment while only 12.9% were treated with either insurance or government funding and 0.4% received free treatment. The Kerala ACS registry included 25,748 patients presenting with ACS to 125 hospitals between 2007 and 2009. Of these, 37% of patients presented with STEMI and only 13% underwent angioplasty during the hospital stay. Although the details about primary PCI are not available, it can be concluded that thrombolysis was the primary modality of reperfusion. Interestingly, admission diagnosis of STEMI was more frequent in rural hospitals and rates of thrombolysis were also higher in rural hospitals.

Thrombolysis in AMI

Of the two available modalities of reperfusion – thrombolysis and primary PCI, thrombolysis has the upper hand in terms of availability of the required infrastructure. In India today, there are at least 10,000 nursing homes, small hospitals which can administer thrombolysis as opposed to about 625 cathlabs required to do PCI. Thus the chances of patients reaching a non-PCI centre are very high in the Indian scenario. This unique delivery system is built into the societal structure in India by the entrepreneurial spirit of the doctor, who invests his own money (often also takes a substantial bank loan) to set up his nursing home. In many cases, the hospital and residence site (of the owner doctor) are one, so an admitted patient gets immediate attention and treatment.

Patients normally report to a hospital or nursing home in the close vicinity of his residence and/or workplace. The doctor has the following choices:

– Thrombolytic reperfusion therapy is administered by the doctor and the patient is stabilised

– The doctor takes a decision to move the patient to a nearby hospital for primary PCI if PCI is available in that city

– In the event of that particular town or city having no facility for PCI, the doctor has no option but to use thrombolytic therapy as the first choice of treatment, and then, if possible, to transfer the patient to another city where PCI is available.

It is not uncommon for the patient to reach a nearby nursing home within a short period of time, 30-40 minutes, early diagnosis is made, and thrombolysis is delivered in the “golden hour”. The unique set-up of a small nursing home with a physician available round the clock makes it possible to avoid the time delays in India. This can be compared to pre-hospital thrombolysis (PHT). PHT was introduced in the western world to minimise the time delay for TT, such that the patient is diagnosed and administered TT in the ambulance. Experience from CAPTIM7 and PRAGUE-28 studies show equivalent outcomes in terms of in-hospital mortality with thrombolysis and PPCI when treated within two to three hours of symptom onset, whereas PPCI is a superior strategy for patients presenting after three hours9. In that respect, PHT (administration of TT during transport) is not possible in India for several reasons, including non-availability of ambulances10 equipped with trained paramedical staff and availability of small nursing homes and ICCUs in the vicinity. In fact, the majority of patients with chest pain reach hospitals in India by private or public transport as seen from the CREATE data. The unique system of care in India at the level of the small hospital(s) allows equivalent outcomes to pre-hospital thrombolysis for patients presenting early.

The usual options of thrombolytic agents include streptokinase (SK) and tenecteplase (TNKTPA). Use of SK has been extensive until recently, i.e., until indigenous cost-effective TNKTPA was made available to Indian physicians11. SK requires a bolus push followed by a continuous infusion for a period of 60 minutes, under close monitoring. Antigenic reactions to SK are also a problem especially for small nursing homes. TNKTPA offers the advantage of single bolus push. A recently published post-marketing registry of TNKTPA of 10,120 patients from India12 shows very good efficacy of this agent with low rates of IC bleeding. Overall, 94.42% of patients had clinically successful thrombolysis, and the rates were highest at 95.62% for patients receiving TT within the first three hours. The mortality reported in this large data was 2.15% which is comparable to published international literature. Availability of indigenously manufactured TNKTPA at one third of the cost of international brands has helped Indian patients and physicians to achieve rapid reperfusion using this single bolus drug.

Primary PCI

Primary PCI had generated significant interest in India in the early days. The first randomised feasibility trial of intravenous thrombolysis and primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction was conducted at Sion Hospital, Mumbai, with the name of Sion Thrombolysis trial (STAT)13. Patients of AMI were randomised to thrombolytic therapy or PTCA. The procedural success rate was 100% with no procedural mortality. In-hospital mortality was 10%. Recurrence of angina occurred in 10% of patients. Realising the importance of recurrent ischaemic events, our group14 published experience with coronary artery stenting in acute myocardial infarction in 1997 for the first time in Asia. In this feasibility study coronary stents were deployed in 16 AMI patients who received stents in an infarct-related artery for suboptimal results of plain balloon angioplasty. One patient died in the hospital on day eight due to subacute stent thrombosis. All patients underwent exercise stress testing at one month and at three months, and coronary angiography at four months or earlier if indicated. At the end of six months follow-up, four patients had a positive exercise test and coronary angiography revealed angiographic restenosis in three, and progression of disease in other vessels in one patient. These results were published well before the famous PAMI trial15 which showed that a strategy of routine stent implantation during mechanical reperfusion of AMI is safe and is associated with favourable event-free survival and low rates of restenosis compared with primary PTCA alone.

The strategy of primary PCI, however, is offered to a very small number of patients in India due to a number of factors. In the event that the doctor takes a decision to transfer the patient for primary PCI, a number of other factors out of the control of the doctor come into play, broadly comprising the following:

Pre-hospital transportation delay

Decision delay. Multiple factors including the financial capacity of the patient influence the doctor’s decision in choosing thrombolysis and/or PCI as the first line of treatment. In a majority cases in the Indian family structure, the treatment decision for the patient is taken by the patient’s family. If the decision is to be taken by a senior member of the family, valuable time is lost in bringing that relative to the site and into the picture so that he may take the “right” decision from the family perspective16.

In-hospital delay, resulting in a door-to-balloon time of up to two hours in non-specialised hospitals with basic facilities. Most of the hospitals in India are equipped with a single cathlab. The cathlab and the consultant need to be available to accept the patient for primary PCI.

For transfer of a patient to a PCI facility in another city, the transportation time can be as much as two and a half to three hours. Transportation delays within metro cities like Mumbai or Delhi with heavy traffic congestion could be similar. These are real-life considerations in India and therefore thrombolytic therapy has greater applicability and relevance in the small hospital set-up.

In the smaller cities in India however, other challenges come to the fore. For transporting the patient for either thrombolytic therapy to a critical care facility or transferring to another city with a PCI facility, the availability of adequately equipped ambulances is a major problem. In many cases, an appropriately equipped ambulance is called from a nearby bigger city to transport the patient to a better facility in a bigger city. In these cases the patient loses the time advantage. Unlike the Western set-ups, air ambulance facilities are very limited and extremely expensive in India.

Time of admission has been observed to make a difference to patient outcome. Very few cathlabs in India have dedicated teams to conduct PPCI round the clock. The availability of cathlab staff and of the consultant is a major issue for patients admitted in the late hours in most of the centres. Even in the Western world PPCI during off hours (generally after 5 pm) is a matter of concern and various guidelines and protocols have been implemented to minimise the delays during off hours. Data from the national registry of myocardial infarction17 show that patients presenting during off hours (5 pm to 7 am) on weekdays and anytime during weekends have higher door-to-balloon times and higher 30-day mortality. Further, the myocardial infarction data acquisition system registry of New Jersey18 showed that patients admitted at weekends with myocardial infarction were less likely to undergo catheterisation and had higher 30-day mortality as compared to patients admitted on weekdays. When PPCI is performed during the off hours, the percentage of failed PCI increased significantly. Specific efforts directed towards minimising the delay in treatment during off hours, like the Mayo Clinic Protocol, have helped to minimise the difference between outcome measures in the United States19. Implementing these types of protocol has numerous limitations in India. In India most of the catheterisation laboratories are managed by a single team comprising two or three interventional cardiologists, technicians and staff nurses. With no alternative being available to the single team, mobilisation of a team during off-duty hours is a herculean task. Thus, most of the hospitals with catheterisation laboratories work on the principle of daytime PCI and night-time thrombolysis.

Despite these limitations most cathlabs offer primary PCI to suitable patients if the logistics permit. The national PTCA registry of India shows a steady growth in the number of primary PCIs performed across the country. The number of PPCIs has increased from 2,956 in 200520 to 14,271 in 2010 which constituted 12% of the total coronary angioplasties performed (data presented at National Intervention Council Meeting, 2011). Interestingly, PPCI was the reperfusion therapy for 40% to 50% of patients admitted with acute MI to moderate volume centres (200 to 1,000 PTCA per year). Use of DES and BMS was equally distributed with 49.3% of patients receiving DES for acute MI in 2010. The use of GpIIb/IIIa inhibitors is also very common with 76% of patients receiving these agents. Of the three available agents, tirofiban is the most preferred agent with 65% of the PPCI patients receiving tirofiban for PPCI in 2010. Other common adjuncts include thrombosuction, especially after publication of the TAPAS trial, and intra-aortic balloon pump in a small number of patients. Other LV assist devices like Impella are extremely uncommon in the Indian setting.

Pharmaco-invasive strategy – best suited for the Indian scenario

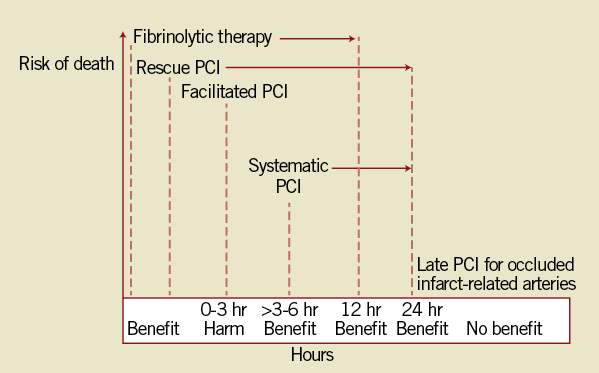

The coupling of fibrinolytic therapy with PCI with the intention of improving the patency of infarct-related artery and clinical outcomes failed to show any benefit over PPCI – rather it was more harmful as shown by the ASSENT-4 PCI21 and FINESSE22 trials. A number of recent trials have helped to clarify the optimal timing of systematic PCI after fibrinolysis23 (Figure 1). The data from the French Registry on Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI)24 also show that PCI within 24 hours of thrombolysis improves outcomes by reducing mortality significantly and helps to bridge the outcome gap between TT and PPCI. There seems to be a window between three and six hours when there is a likely benefit, as indicated by the Combined Abciximab Reteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS)25 and Trial of Routine Angioplasty and Stenting After Fibrinolysis to Enhance Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TRANSFER AMI)26. This pharmaco-invasive strategy is very important in the Indian perspective where thrombolytic therapy can be administered immediately by a local physician and then the patient can be transferred for PCI to the nearest PCI facility within 24 hours to optimise the gains of thrombolytic therapy.

Figure 1. Impact of PCI with fibrinolytic therapy. Fibrinolytic therapy reduces mortality up to 12 hours after symptom onset. Rescue PCI is also beneficial for on-going symptoms or failure of resolution of ST-elevation by 50%. Facilitated PCI within three hours of administration of fibrinolytic therapy is harmful. Systematic PCI between three and six hours after fibrinolysis appears to be beneficial. After six hours, there may be benefit. Opening an occluded infarct artery after 24 hours from symptom onset provides no patient benefit23.

Cost implications of reperfusion therapy

While the penetration of medical insurance in India is slowly increasing, the modality of delivery of compensation comes with more than its fair share of problems. In India there is no system of blanket permission by the insurance agencies to hospitals to treat the patient first and fulfil the documentation requirements subsequently. This is particularly pertinent in the case of AMI where immediate treatment is the need of the moment. Even those in government jobs where the government takes care of the medical compensation in cases of illness and hospitalisation, documentation hassles play a major role in delaying the decision taken for appropriate and timely management of AMI. The documentation process itself takes three to four hours and hence the PCI-eligible patients may end up with TT. The only remedy for these non-medical illnesses is for the government, the insurance sector and all the other players to understand that timely treatment can make the difference between life and death of the patient and put regulated systems in place that will address these very important and relevant issues.

Improving outcomes in India

Symptom recognition by the patient is still not optimal and significant numbers of patients do not seek immediate attention after developing chest pain. Public education is the key to early reporting for chest pain. Physicians can play a very important role in increasing awareness about the symptoms of myocardial infarction and need to take an active part in disseminating the knowledge at the community level. Physicians need to be educated and motivated to participate in community-level activities especially in semi-educated and uneducated classes of the society so that patients do not waste the “golden hour”.

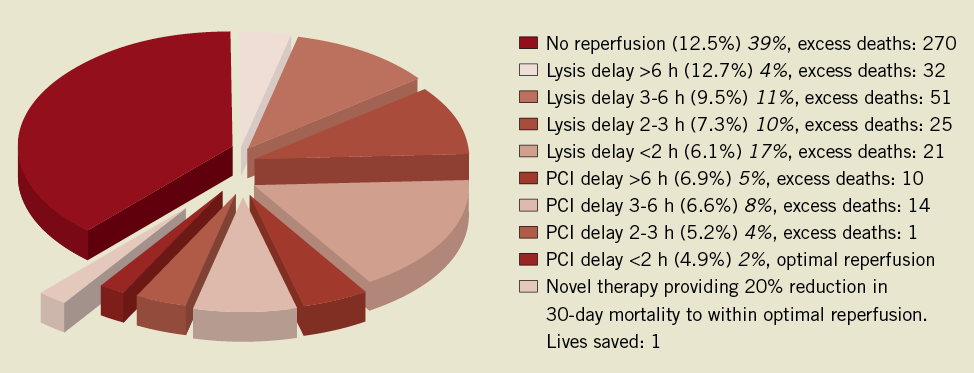

The advances in the technologies of reperfusion therapy are occurring at a very rapid pace. Since availability of cathlab facilities and required finances for PPCI are scarce, TT is the best option when it comes to on-the-ground reality that 40% of STEMI patients do not receive any reperfusion therapy in STEMI. This is the most important missed opportunity when it comes to improving the outcomes of STEMI27 (Figure 2). The potential for greater improvements in patient outcome can be achieved with improved care delivery rather than the potential gains from therapeutic innovations. Recognition of this fact can help everyone in the chain from patient to healthcare delivery provider to shorten the time to reperfusion, thus maximising myocardial salvage. Round-the-clock availability of a cathlab facility is limited to very few centres in bigger cities. Necessary efforts to have at least one team competent to perform PPCI, possibly per city or per locality, can solve the problem. However, this is easier said than done considering the current medical practice. Recognition of failed thrombolysis is equally important and should prompt the physician to consider transfer of the patient to the nearest PCI facility for an early intervention.

Figure 2. Missed opportunities in reperfusion for STEMI. Estimates of the proportion of all STEMI patients receiving either fibrinolysis or catheter-based reperfusion (the percentage in italics) at various degrees of delay, combined with literature-based estimates of mortality observed with the reperfusion modality and associated delay (the percentage in parentheses). Excess deaths estimated by multiplying the excess mortality rate above primary PCI undertaken within two hours of onset of symptoms by the proportion of patients at risk in a cohort of 10,000 patients presenting with STEMI27.

Reimbursement agencies (through insurance or employer, including government offices) must have blanket permission for their beneficiaries to obtain suitable treatment for AMI without pre-authorisation. All these agencies need to develop systems to pay the treating hospitals directly for the treatment of their beneficiaries. This will allow the small set-up to concentrate on medical management of the AMI patient rather than worrying about the cost of the therapy.

The scenario is rapidly changing in India. The current number of cathlabs in India is expected to double, passing the 1,000 mark in the next couple of years. This would mean the availability of cathlabs in most of the medium-sized cities and the possibility of offering PPCI to many, more deserving patients. Various agencies such as government, cardiology societies and doctors have to come together to develop a national strategy. The Kovai Erode STEMI initiative28 in the state of Tamilnadu is one such example which aims at improving the STEMI care in India through the collaboration of various hospitals and government agencies. We also need to train a younger generation of interventional cardiologists who can perform PPCI safely. Availability of PPCI in close proximity to the patient and the availability of a cardiac ambulance in every city, coupled with an increase in health insurance, can pave the way for most patients to get suitable reperfusion in AMI, thus translating scientific evidence into the “Stent for Life” reality.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.