Abstract

Acute initial management of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is based on a precise clinical and electrocardiographic diagnosis. Initial risk stratification in the pre-hospital phase is the key step. The last step, adequate patient routing, is decided based on emergency level and reperfusion strategies, considered right from the pre-hospital phase. The management of a patient with an ACS requires close collaboration between emergency physicians and cardiologists, according to simplified protocols for easier access to catheterisation. The next challenges for the pre-hospital management of ACS are based on:

– precise knowledge of new antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs by the emergency physicians, in order to adjust their prescriptions to the patient profile;

– developing co-operation between hospitals, according to regional specificities (geographic considerations and distribution of PCI centres) in order to reduce access time to catheterisation rooms;

– organising the healthcare network, where the SAMU has an essential role in coordinating the different medical actors;

– regular analysis of the evolution of our professional practices, considering, e.g., the guidelines of the “HAS” (French official healthcare guidelines institute);

– integrating pre-hospital medicine in health prevention programmes;

– improving our understanding of the population’s presentations of coronary artery disease, in order to encourage the patients and their families to call the EMS as soon as possible.

The challenge of the emergency physician is to adapt the strategies to the patient’s needs.

Introduction

Cardiological activity represents on average 20% to 40% of the activity of the French Mobile Intensive Care Unit (MICU), of which 30% is acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This activity is not limited to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Indeed, the incidence of STEMI has decreased1, but proactive strategies for management of ACS without ST-elevation (NSTEMI) are now a major issue. ACS care is constantly changing and evolving, due to better understanding of the pathophysiology and major therapeutics over recent years2. Many studies have led to changes in the diagnostic and prognostic approach by comparing the efficacy and safety of drug therapies and/or interventional therapies. Paradoxically, the growing number of clinical trials has sometimes made the choice more difficult for practitioners dealing with coronary emergencies. European and American guidelines have clarified the situation for STEMI, and stressed the essential role of the MICU3. Early administration of a combination of antiplatelet therapy before reperfusion (thrombolysis or angioplasty) has demonstrated its effectiveness43,44. The pre-hospital therapy for NSTEMI is far more complex. In these patients the balance between reperfusion quality and haemorrhagic risk is very delicate. The use of a risk score (GRACE, CRUSADE) in the pre-hospital setting cannot be done easily.

In this highly innovative context, a major challenge for the emergency physician is to adapt his strategies to the international guidelines and to stay as close as possible to the patient’s needs, before sending him to the cardiologist, as soon as possible and in an adapted structure. STEMI patients and high-risk non-STEMI patients must be sent directly to an institution with cathlab facilities available 24 hours per day avoiding inter-hospital transfers45,46.

First challenge: act fast

Apart from the choice of reperfusion technique, giving early treatment and activating the coronary emergency network’s actors (emergency physicians and cardiologists) as soon as possible is a key factor in the success of reperfusion4. It is therefore essential for the MICU teams to intervene as soon as the patient calls. However, up to 2010, delays before support were often still unacceptable, and very few patients received all recommended treatments timeously5. Only 15% of patients referred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were treated within two hours6,7.

Second challenge: recognising and identifying patients at risk

THE DOCTOR’S PERSPECTIVE

To adapt the means and avoid sending unnecessary MICU teams, the ideal system for sorting calls must have a high sensitivity and high specificity. Some data are needed after the first call to get through to the medical dispatching centre or emergency medical system (EMS) call centre (personal and family history, characteristics of pain, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and current medications). So far, however, the decision support software (algorithms) is disappointing: excellent sensitivity (99%) but low specificity (2%), and no data is in favour of a system based on estimation and subjectivity of experts to determine the sending of a MICU8.

THE PATIENT’S PERSPECTIVE: DO NOT WAIT

The time taken for a patient to decide is usually the most critical period. Part of the delay in treatment occurs before the first medical contact and is often attributable to the patient himself. Patients calling late have certain individual characteristics: they are more often elderly, female, diabetics, they have atypical symptoms, or have a lower social status. Things are changing positively through public initiatives undertaken in the United States9 and Europe4. Repeated information campaigns, delivering an easy-to-understand message on the characteristics of symptoms and the importance of time to “save the heart”, are effective10. They encourage calling the emergency number of the local EMS directly in case of chest pain to shorten time to reperfusion11. Their impact led to an increased use of the EMS. Unfortunately, the effects of public campaigns are temporary. Despite mixed results, other methods to raise public awareness and to motivate an earlier call in coronary patients are tested in prevention programmes12. Indeed, a better understanding of how patients and families make the decision to alert the emergency services is essential. Awareness of the population’s presentations and beliefs of coronary disease is useful to assess the individual risk perception, and thus to understanding better the severe underestimation by the patient especially in the elderly and women. These patients wait a long time after onset of pain before calling and the first call is often to their GP and not to the local EMS.

Third challenge: quick diagnosis

In France and many other European countries, the decision to initiate treatment relies on early diagnosis by the pre-hospital emergency physician, based on physical examination and ECG.

The qualifying ECG is the key to the diagnosis, regardless of where it is performed13. Its interpretation by an experienced physician will allow the diagnosis of STEMI or NSTEMI. It is the key determinant of a time for reperfusion of STEMI, either by pre-hospital thrombolysis (PHT) and/or by primary angioplasty. We can consider the first ECG as the first medical contact, and the delay between first medical contact and reperfusion according to the guidelines determines the choice of reperfusion3. If the delay is more than 120 minutes, lytic therapy must be administered as soon as possible, and PHT in these conditions seems to be the best option. Telemedicine offers new perspectives. For hospitals far away from specialised centres, tele-expertise can be performed by a specialist remotely, and a quick transfer by a medical team to the catheterisation laboratory can be organised.

THE USE OF A BIOLOGICAL DIAGNOSTIC TEST

As far as STEMI is concerned, the revascularisation decision must be immediate, because waiting for any biological blood test would delay reperfusion. Started in the MICU before reaching the hospital thanks to an on-board laboratory, and repeated in hospital, troponin measurement is an important diagnostic element. It influences the therapeutic strategy for NSTEMI but requires more than two hours after symptom onset before the markers can be detected2. A biomarker rising almost immediately could be useful to detect “high-risk” NSTEMI patients. The ultrasensitive troponins available in the emergency department cannot be exported to the pre-hospital setting14. Copeptin, the vasopressin prohormone, could improve early diagnosis of NSTEMI (within the first four hours). Combining troponin and copeptin may eliminate the diagnosis of infarction with greater security15.

Fourth challenge: ischaemic and haemorrhagic risk stratification

Risk stratification is the cornerstone of the therapeutic management of NSTEMI13. Accurate stratification of the ischaemic risk (death and acute thrombotic complications) predictive scores (TIMI, PURSUIT, GRACE) is recommended16. However, they remain difficult to use in the pre-hospital environment. Also, the validation of a clinical risk score remains a challenge: not only ischaemic risk but also haemorrhagic risk (inherent to choosing appropriate antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs) should be evaluated in the pre-hospital phase2,13. Indeed, bleeding is steadily leading to increased mortality in a “dose-dependent” way17. The good regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy in the pre-hospital setting is balanced between two options: a simple choice for all patients, or a more complex strategy adapted to the age, weight and clinical history of the patients.

Fifth challenge: deciding on the optimal reperfusion strategy

IN STEMI

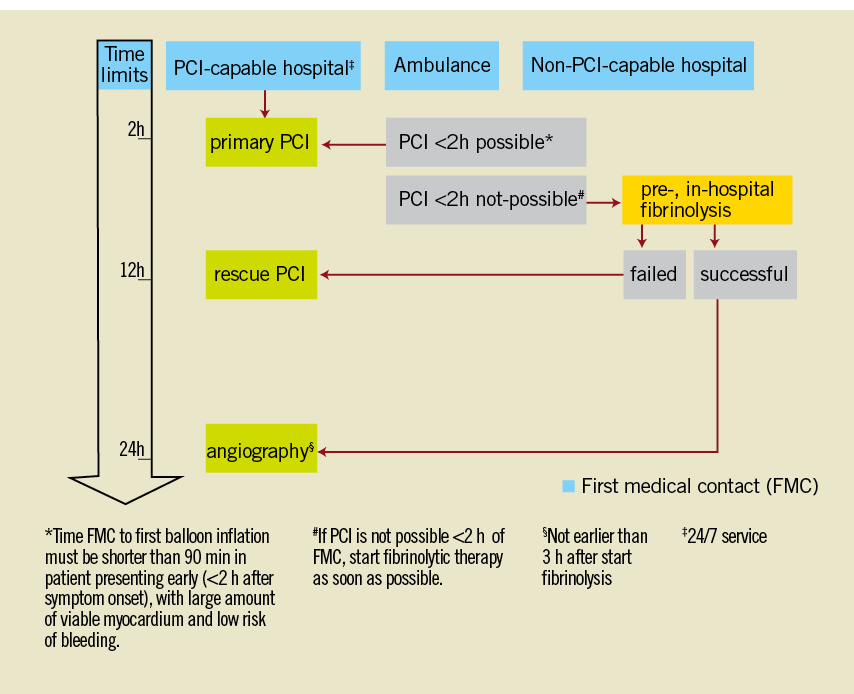

Optimal emergency treatment is now well codified3. The guidelines highlighted the essential role of the MICU to initiate the choice of the reperfusion strategy3. Access to angioplasty within less than 90-120 minutes after first medical contact is the main discriminating factor (Figure 1). Accessibility to the catheterisation laboratory must take into account local conditions (distance, traffic conditions, weather)7,18. PPCI is recommended, if performed by an experienced operator within 120 min after the qualifying electrocardiogram. This acceptable delay should in some patients be reduced to 90 min (young subject, anterior necrosis, very high-risk patient)3. Data from registries show that in real life these time goals are extremely difficult to achieve. Pre-hospital thrombolysis is an alternative when primary PCI cannot be guaranteed within 120 min4. Its benefit and superiority when administered within two hours has been demonstrated41. The management strategy after thrombolysis remains controversial. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) suggests performing a coronary angiography in all thrombolysed patients within 24 hours19, while the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) restricts this strategy to high-risk patients only20. While some studies clearly demonstrated the interest of PHT followed by PCI, the “optimal” time to perform coronary angiography remains controversial21. It may be delayed to between three and 24 hours to avoid the prothrombotic period and thus reduce the risk of re-occlusion3. In case of no signs of reperfusion after thrombolysis, “rescue” PCI must be performed as soon as possible.

Figure 1. STEMI management strategies in 20103.

IN NSTEMI

Despite the updated guidelines, it is often difficult for the clinician to determine optimal management for these patients13. Faced with a NSTEMI, choosing an appropriate therapeutic strategy leads to three questions: 1) the pharmacological environment; 2) routing the patients to the appropriate structure (with or without “cathlab”); and 3) delay before diagnostic coronary angiography2. Any patient suspected of a NSTEMI should be evaluated immediately by a qualified physician, routed according to risk, transported by a MICU with a physician on board and re-evaluated later in hospital. Taking an individual and personalised treatment decision based on risk/benefit is a new challenge for emergency physicians. The emergency physician must weigh the comorbidities and the clinical findings, and evaluate the pharmacological and interventional environment. The decision can translate into performing coronary angiography in immediate life-threatening emergencies or ideally within 48 hours in patients with medium to high risk13.

Sixth challenge: the right use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents

The management of ACS should be integrated into up-to-date therapeutic strategies involving early use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents. The aim is to facilitate spontaneous reperfusion to stabilise atherosclerotic plaque and to limit thrombus extension, while ensuring pharmacological impregnation at the time of mechanical reperfusion. Numerous international studies have attempted to clarify their impact on morbidity and mortality because of a real risk of bleeding. Therefore, combining antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants (two or three) has become a major issue. Moreover, optimal combined dose has rarely been tested22. Three major therapeutic classes are available: anti-ischaemic agents, in particular beta-blockers and nitrates, anticoagulants (unfractionated heparin [UFH] , low molecular weight heparin [LMWH], fondaparinux or bivalirudin), and antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors). The prescription depends on the initial risk, as perceived by the emergency physician, the recurrence of symptoms and biological data.

The antiplatelet agents

Aspirin is the routine treatment given as soon as possible to all patients, orally (150-325 mg) or intravenously (250 mg).

Among associated therapy, thienopyridines and new inhibitors of platelet aggregation may legitimately be used by emergency physicians.

Clopidogrel - a bolus of 300 mg is recommended for patients less than 75 years old receiving PHT23. The ESC guidelines recommend 600 mg of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PPCI3,24. Administration of clopidogrel two hours before the procedure is associated with faster ST-segment resolution (90-180 minutes), increased incidence of TIMI 2-3 and a lower rate of recurrence and death25. Earlier on, attitudes were more controversial. Some considered routine clopidogrel before diagnostic coronary angiography useless or even dangerous26. Others argue that to wait until diagnostic coronary angiography to avoid bleeding risk in case of CABG (bypass surgery) is unfounded27. In 2012, the question as to whether there should or should not be a pre-treatment with clopidogrel is unresolved (ARMYDAS, CIPAMI). It is therefore important to reassess this practice considering the arrival of new, more powerful drugs. These issues are a real clinical challenge for a more rational use of these new oral antiplatelet agents in the pre-hospital setting. Prasugrel and ticagrelor are both recommended by the ESC guidelines for STEMI and high-risk NSTEMI as soon as possible for patients undergoing PCI but their use in the pre-hospital phase is still under investigation.

Prasugrel is a new P2Y12 inhibitor, twice as powerful as clopidogrel for inhibiting platelet aggregation (with a lower rate of non-responders), and it has a faster onset of action. The results of TRITON TIMI 38 showed a significant reduction of ischaemic events in the STEMI subgroup of patients treated with PCI (9.9% vs. 12.1%) and a similar rate of bleeding28. Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider prasugrel in pre-hospital STEMI patient care, carefully respecting the precautions (bleeding, prior stroke or TCI, low body weight and patients over 70 years old) for use. Clinical trials are currently underway in NSTEMI with elevated troponin to clarify the use of prasugrel in the pre-hospital phase (ACCOAST).

Ticagrelor is a “rapid and reversible” antiplatelet agent. With its effectiveness in relation to total mortality (4.5% vs. 5.9% for clopidogrel), it could be the preferred pre-hospital treatment of tomorrow29. Its short half-life, its reversibility and its safety profile appear particularly suitable for pre-hospital use. The effect of a loading dose for STEMI patients in the pre-hospital setting is currently being tested in an on-going trial (ATLANTIC).

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPI) should probably be used in the cathlab only according to the guidelines30. The FINESSE trial was negative but the delay between onset of pain and administration of abciximab was quite long. On the other hand, ON-TIME 241 with tirofiban, using a surrogate endpoint, was positive. For a young patient with a large infarct and a delay from onset of pain to primary PCI of less than one hour, there could still be a benefit of pre-administration of glycoprotein inhibitors, but this hypothesis must be reinforced by new trials.

Anticoagulants integrated into early pre-hospital strategy

Unfractionated heparin (UHF)

UHF is the recommended anticoagulant as the primary therapy in the actual STEMI guidelines3.

Enoxaparin

– In STEMI: enoxaparin is an interesting approach. Its effectiveness and safety has emerged as the reference low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), with established clinical benefit and a significant reduction in death or reinfarction. Its safety was confirmed in a large meta-analysis31. It is currently recommended in pre-hospital use for all patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy32. For patients undergoing primary PCI, the ATOLL trial was close to demonstrate superiority over UFH (net clinical benefit 10.2% vs. 15% for UFH) (0.5 mg/kg followed by 0.1 ml/kg subcutaneously)33.

– In NSTEMI: LMWH has been validated, with or without associated coronary angiography. SYNERGY (enoxaparin vs. UFH) in an up-to-date design (aspirin + clopidogrel + PCI) confirmed the efficacy and relative safety of subcutaneous enoxaparin adjusted to the weight (0.6 to 1.0 IU/ml). In unselected patients, it significantly reduced the death or infarction risk, and suggested that lower doses could decrease the bleeding risk in case of selective PCI34.

Fondaparinux appears to be as effective in terms of ischaemic risk, and improves long-term morbidity and mortality, reducing bleeding and stroke risk, but is not recommended in patients requiring emergency angioplasty.

In the ESC NSTEMI guidelines, fondaparinux is recommended as the reference anticoagulant in patients where the need for angiography is not urgent13,35.

Bivalirudin: this hirudin analogue proved to be a life-saving drug in patients with STEMI when given in the cathlab to patients treated by PPCI, but it has not yet been evaluated in the pre-hospital setting. The clinical benefit of bivaluridin (vs. UFH + glycoprotein inhibitors) results in lower bleeding risk (39%) with a similar reduction in antithrombotic efficacy. This benefit was still present at one year (absolute risk reduction 1.7%) and was also associated with a decrease in mortality36. In moderate or high-risk NSTEMI, ischaemic performance is equivalent to UFH + GPI but the bleeding profile is favourable (ACUITY, ISAR REAC 4)13,37. EUROMAX (bivalirudin vs. UFH + PCI <2 hours) is a randomised study designed to evaluate bivalirudin in pre-hospital STEMI patients. Results are expected in 2012.

Seventh challenge: to provide proper patient routing

– In STEMI: direct transfer to the catheterisation laboratory reduces mortality. It is thus essential to promote direct admission to these units by the MICU teams. Everything must be done to offer PPCI as soon as possible to STEMI patients.

PPCI is a IA recommendation in the current guidelines.

If the delay of two hours between first medical contact and PPCI cannot be respected, pre-hospital thrombolysis or a pharmaco-invasive approach followed by direct transfer to the cathlab for early PCI reduces morbidity and mortality compared to conservative ischaemia-guided treatment39,42. It is therefore essential for the physician to identify from among the thrombolysed patients those who should be transferred as soon as possible to the cathlab. OPTIMAL’s goal was to identify quickly the 40%-45% of patients who will not respond to fibrinolysis, in order to organise their immediate transportation to the cathlab38. The results of several recent studies argue for an early transfer to the cathlab after thrombolysis, but the optimum time period between “successful” fibrinolysis and PCI is not yet clear21,39. A time span of three to 24 hours provides the best results, with a lower mortality, when PCI was performed more than three hours after fibrinolysis (1.6% vs. 3.7% when the PCI was performed within the first three hrs)25. The STREAM study, comparing fibrinolysis with delayed PCI to primary PCI may give useful information on this optimal time.

– In NSTEMI: the timing of an invasive strategy for high-risk patients should be tailored as soon as possible according to risk in three categories: urgent, early and conservative, depending on the patient’s risk (GRACE score)13. Ideally, all high-risk non-STEMI patients must be transported by the MICU to cathlab facilities avoiding a second inter-hospital transfer.

Eighth challenge: building an efficient healthcare network

The current situation can be improved by setting up networks in which the local EMS organisation, cardiac intensive care units and cathlabs cooperate closely. This system will offer PCI access to the majority of patients within the recommended time.

Ninth challenge: involving a broader range of populations in our studies

Actual clinical research is often limited to relatively homogeneous groups, and some individuals (elderly >75 years) are systematically excluded from research protocols without justification. In the future, including elderly patients in these protocols should allow a more realistic approach, considering reduced ischaemic events vs. increased haemorrhagic risk phenomena in our ageing population.

Conclusion

The benefits of accurate diagnosis and risk stratification followed by treatment in the ambulance have been demonstrated. Powerful new drugs constantly enlarge the therapeutic possibilities for the emergency physician, but we still need more randomised trials adapted to the pre-hospital setting. Nevertheless, before discussing these “revolutionary” drugs, we should apply validated practices to improve catheterisation laboratory access, to comply with the guidelines in terms of delay. Through the national registries (FAST-MI, Stent for Life), evaluation of professional practice is possible and will enable us to compare the new strategies in order to optimise ACS management. These registries are the vital link between clinical trials and daily practice. Beyond their innovative qualities, these studies should take into account ethics, collective constraints and local conditions. Better coordination of local health facilities and specialised services should ensure access to quality care for all. Reflection on structured networks for coronary emergencies should continue. Tomorrow’s coronary emergency management will be more “targeted” and individualised and therefore more complex. Emergency physicians will have to cope with interesting therapeutic innovations.

Conflict of interest statement

C. Adriansen is a speaker for Lilly, and Boehringer Ingelheim. P. Goldstein is a speaker and consultant for Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, The Medicines Company, Bayer, and Sanofi. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.