In the year of its 40th anniversary, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has evolved from balloon angioplasty over bare metal stents to drug-eluting stents (DES) and has, more recently, witnessed the advent of fully bioresorbable scaffolds (BRS). New-generation DES constitute the current benchmark in PCI and are indicated in all patient and lesion subsets1, with excellent early (one-year rate of stent thrombosis <1%, one-year clinical restenosis rate <5%) and late outcomes (rates of very late stent thrombosis beyond one year: 0.1-0.2% per year, rates of clinical restenosis beyond one year: 1-2% per year)2,3. Indeed, PCI has matured into the most frequently performed revascularisation procedure due to its life-saving performance among patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes4,5, as well as rivalling outcomes compared with coronary artery bypass surgery among patients with multivessel coronary artery disease, including left main disease6,7.

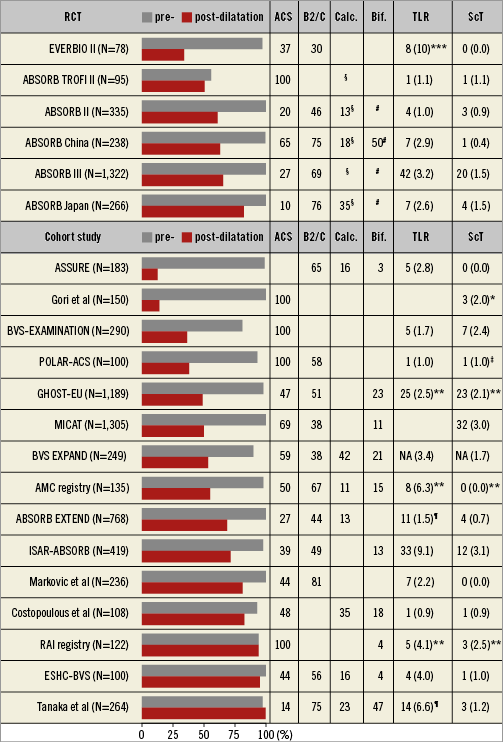

Fully bioresorbable scaffolds were introduced to eliminate permanent caging of the vessel wall by metallic prostheses with the aim of restoring vessel physiology8. In view of the favourable outcomes achieved by current-generation DES, BRS do not address an obvious unmet clinical need but rather represent a technological advance with any hypothetical benefit to be determined only during very long-term follow-up. A synthesis of data from randomised controlled trials (RCT) comparing BRS with metallic everolimus-eluting stents (EES) at one year showed similar clinical (albeit inferior angiographic) efficacy as well as increased rates of target vessel myocardial infarction and scaffold thrombosis (ScT)9,10. More recently, the ABSORB II study failed to reach its co-primary endpoints of vasomotion and late lumen loss at three-year follow-up. Moreover, BRS were associated with an excess in target lesion revascularisation (TLR; 6% versus 2%, p=0.04) and ScT (3% versus 0%, p=0.03) at three years11. To what degree device, operator (implantation) technique or lesion (patient) factors contribute to the outcomes of BRS forms part of ongoing studies. With respect to the implantation strategy, a recent post hoc analysis of observational data reported a lower risk of ScT at one year when a BRS-specific implantation strategy aiming at adequate lesion preparation and systematic scaffold post-dilation had been pursued12. In this context, it is noteworthy that systematic post-dilatation was implemented on average in less than 50% of previously published studies and intracoronary imaging was used infrequently (Figure 1). While the implementation of such a device-specific implantation strategy will undoubtedly affect early (within one year) outcomes, its impact on long-term results and, in particular, the risk of very late scaffold thrombosis (VLScT) is the subject of ongoing debate.

Figure 1. Randomised controlled trials and cohort studies investigating the Absorb BVS. Data reported as percentage or number of events (cumulative incidences) for any TLR and definite or probable ScT at one year, unless otherwise specified. *1 month. **6 months. ***9 months. ¶ischaemia-driven TLR. ‡definite ScT. §heavily calcified lesions were excluded. # major bifurcation lesions were excluded. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; NA: not available; RCT: randomised controlled trial; ScT: scaffold thrombosis; TLR: target lesion revascularisation

The observational study of Tanaka et al sheds further light on this relevant issue by reporting clinical outcomes in 264 patients with 400 coronary lesions who underwent Absorb BVS implantation by experienced operators implementing a specific implantation strategy with routine predilatation using non-compliant balloons (97.3%), adequate lesion preparation with the use of adjunctive devices such as scoring and cutting balloons (15.3%) or rotational atherectomy (4.8%), a slowly increasing inflation pressure followed by a prolonged inflation and routine post-dilatation using non-oversized, non-compliant balloons (99.8%) at high pressures (20.8±4.5 atm). In addition, results were optimised using intracoronary imaging in the majority of cases (85.8%)13. The cumulative target lesion failure rate including death, target vessel myocardial infarction and clinically driven TLR amounted to 7.9% at one year and 11.6% at two years using this specific implantation strategy.

Clinically driven TLR occurred in 6.6% of patients at one year and 10.4% of patients at two years. Definite or probable ScT was reported in three patients (1.2%) within two years. The most evident limitation of this study relates to the limited follow-up period and the small sample size. Despite the report of two-year outcome data, only 75% of patients were followed for at least eight months and 50% for 18 months, rendering any long-term assessment inconclusive. Notwithstanding the incomplete follow-up, the frequency of clinically driven TLR amounted to 6.6% at one year, which is almost double the rate previously reported in all-comers trials using the metallic EES counterpart14. Although lesion complexity including bifurcations (47%) and calcified lesions (23%) is acknowledged, it appears that even under the best of circumstances, including a dedicated implantation strategy, intervention by expert operators, and guidance by intracoronary imaging, the device per se imposes limits that are challenging to surpass in complex settings. Unfortunately, the authors fail to present insights into the association of post-procedural intracoronary imaging findings and the subsequent risk of restenosis or scaffold thrombosis, which would have been helpful in order to elucidate the mechanisms of device failure following an optimised device implantation strategy.

As it relates to the implications of underlying lesion characteristics, the post hoc analysis of ABSORB Japan by Ohya and colleagues in this issue of EuroIntervention provides additional insights with a particular focus on calcified lesions. The in-device minimal lumen diameter was similar irrespective of the presence (BVS: N=72 and EES: N=42) or absence (BVS: N=181 and EES: N=89) of angiographically assessed calcifications among patients randomly assigned to Absorb BVS as compared to the metallic EES immediately after the procedure and at 13-month follow-up15.

The authors found that post-procedural and follow-up in-device minimal lumen diameters were comparable between calcified and non-calcified lesions in both device groups and concluded that moderate or severe lesion calcification does not impact on angiographic outcomes using the Absorb BVS. Of note, heavily calcified lesions or those requiring lesion preparation such as rotational atherectomy were excluded from the ABSORB Japan study according to the study protocol, suggesting the exclusion of lesions with an extensive degree of calcification. Thus, the absence of interaction between calcification and indices of device success can only be considered valid in selected low-risk lesions as encountered in pivotal trials such as the ABSORB Japan study and should not be applied to heavily calcified lesions encountered in routine clinical practice. On a different note, it may be questionable whether fully bioresorbable scaffolds are able to provide fully restorative vessel healing in significantly calcified lesions in view of the restricted ability for circumferential device expansion as well as late vessel remodelling.

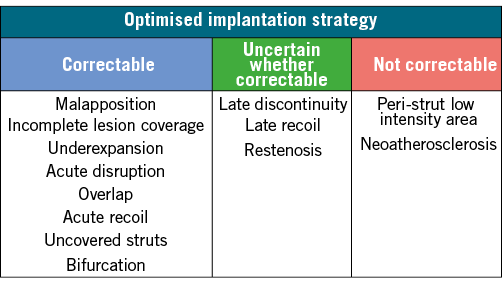

The detailed analysis of ScT by means of high-resolution optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides important insights for unravelling the multifactorial mechanisms leading to scaffold failures. While large-scale clinical trials addressing the risk of ScT are ongoing, a series of ScT cases investigated by OCT has already been published. Sotomi et al have summarised all published cases of early (N=17), late (N=10) and very late (N=16) ScT that underwent intracoronary imaging at the time point of thrombosis16. The most frequent findings associated with early ScT were malapposition (24%), incomplete lesion coverage (18%), and device underexpansion (12%).

Intracoronary imaging observations more germane to late and very late ScT encompassed malapposition (35%), discontinuity (31%), peri-strut low intensity area (19%), uncovered struts (15%), device underexpansion (15%), incomplete lesion coverage (12%), recoil (12%), and restenosis (8%). Although publication bias must be acknowledged as well as the lack of a control group, the systematic review provides a notable insight: approximately half of the patients suffering from late or very late ScT showed causes of ScT that are less likely to be modified by an optimised implantation strategy (Figure 2). Loss of radial force during the absorption process resulting in late recoil, and loss of structural integrity leading to scaffold discontinuity are findings that are specific to BRS17 and difficult to prevent effectively by a dedicated lesion preparation and device implantation strategy at the time of the index procedure. Whether an optimised implantation strategy such as, for example, OCT-guided PCI aiming at complete device apposition and optimal scaffold expansion will effectively prevent these late occurring structural abnormalities is currently unknown. Moreover, the pathologic correlates of peri-strut low intensity area and its clinical significance still need to be fully elucidated but are dissociated from implantation technique. Instead, they may be related to biologic phenomena involved in the polymer bulk degradation and hypersensitivity reactions and inflammatory responses against the polymer components during absorption.

Figure 2. Mechanisms associated with late and very late scaffold thrombosis and their (partly hypothetical) relation to implantation technique. Late discontinuity refers to a discontinuity leading to malapposition.

To answer conclusively the question as to whether optimised device implantation may overcome the increased risk of very late device thrombosis and restenosis, an RCT would be required with a metallic DES control group as well as a BRS control arm without a dedicated implantation strategy. Such a study is unlikely to be performed with current-generation BRS and, as a result, we will need to rely on careful analysis of ongoing studies. The cohort study by Tanaka et al suggests that the implementation of an optimised implantation strategy may not fully approach the results obtained with current-generation DES, calling into question the use of BRS in complex lesions. Similarly, the analysis of Sotomi et al indicates that approximately half of scaffold thromboses are potentially related to the degradation process of fully bioresorbable devices. Whether this can be effectively prevented by an optimised implantation strategy remains uncertain to date and requires further studies. While prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy has been shown to diminish the risk of stent thrombosis beyond one year with the use of metallic stents, the impact on the risk of scaffold thrombosis has not been investigated and is complicated by the variable degradation time. The observation of degradation-related processes is of concern and warrants the close monitoring of the long-term results of ongoing large-scale RCTs (ABSORB III [NCT01751906], ABSORB IV [NCT02173379], AIDA [NCT01858077], COMPARE ABSORB [NCT02486068]). Careful and comprehensive investigation into the underlying mechanisms of device failure using intracoronary imaging at the time of thrombosis or restenosis will be instrumental in developing preventive strategies that overcome current safety concerns attributable to the device.

Conflict of interest statement

S. Windecker has received research grants to the institution from Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences and St. Jude. L. Räber has received grant support to the institution from St. Jude Medical. K. Yamaji has no conflicts of interest to declare.