As I complete my 10-year term as editor-in-chief of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, I will reflect on this period when the opportunities to publish good work rose to new heights and when that opportunity was a major factor in stimulating good work. I will also praise the collaborative spirit that has resulted in “good globalisation” of this, still young, subspecialty.

One might divide interventional cardiology into four 10-year eras. The first, from 1977 to 1987, I will call the birth and childhood. We were very excited after Andreas Grüntzig delivered this infant but we could barely crawl, and the early steps were indeed clumsy. Second was the period from 1987 to 1997 –the new device era, or our adolescence. We were wild and experimented with many things, some of which were destructive (think directional atherectomy and laser balloon), and some actually enhanced our growth and development (think stents). The third 10 years –1997 to 2007– brought us to adulthood with drug-eluting stents and the early application of technology to solve problems of structural heart disease. During these 30 years, major progress in interventional cardiovascular medicine transformed practice. Primary PCI became the “law of the land” for treating myocardial infarction, and the circumstances in which PCI could be preferred over surgery became better defined. Despite these important endeavours the venues for publishing the results of this work were limited. The Society for Cardiac Angiography and Intervention had, for all these years, published Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, but most of the authors of papers describing trials and novel developments were beating on the door of general cardiology journals such as the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), Circulation, and the European Heart Journal. If they were unsuccessful there, many of them moved on to other general cardiology journals. This vacuum, as some called it, led to discussions about new journals to publish within the narrower scope of interventional cardiology in order to appeal to those with a more focused interest. Others did not view this as a vacuum at all and felt that proliferation of more journals was counterproductive as there were not enough good investigations to warrant more space in the literature. As it turned out, all three major cardiology organisations –the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and the European Society of Cardiology– decided to go forward with subspecialty journals. Interventional cardiology was one, but others in heart failure, electrophysiology, imaging, etc., were also launched.

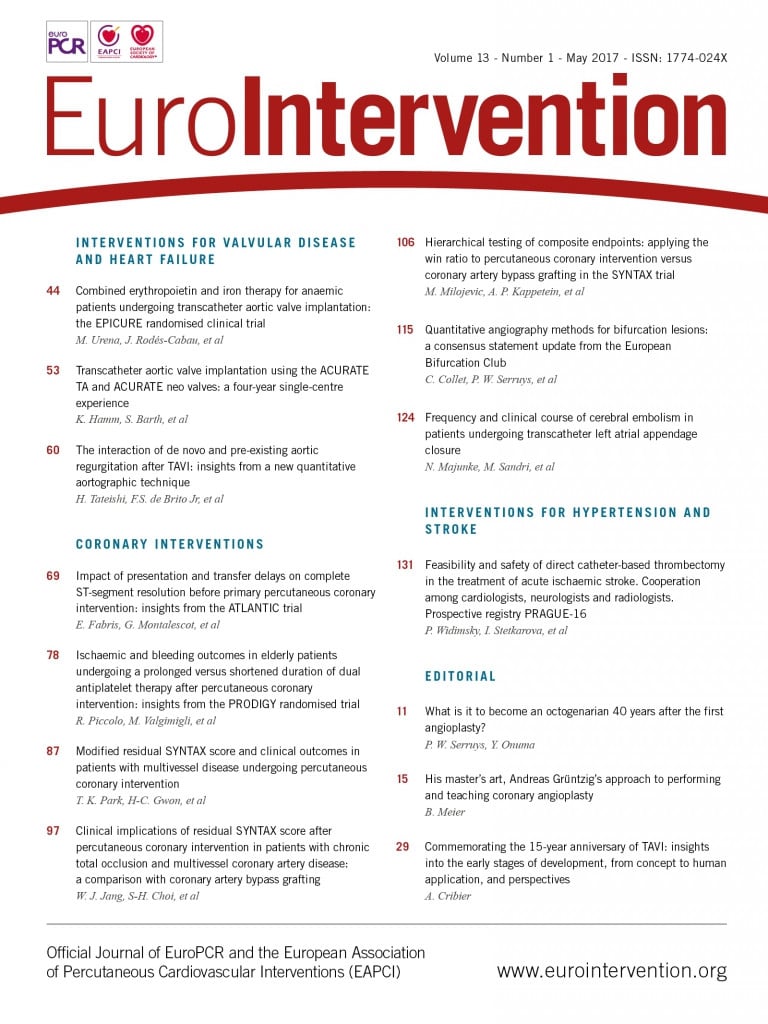

How has it worked out? I must confess that I have always had mixed feelings about the separating of cardiology into subspecialties. During my presidency of the American College of Cardiology, I tried to emphasise the value of subspecialty practitioners remaining in the house of cardiology. However, some separation was inevitable. Electrophysiology had already become a separate universe, with the practitioners of that discipline having little connection with the rest of cardiology. But for interventional cardiologists it was different. We looked after our patients’ problems across the spectrum from prevention to decisions regarding surgical intervention. Most of us are not in the cathlab all day. However, “birds of a feather” and all that is indeed operative. Articles reporting outcomes of new-generation stents or changes in antithrombotic management are going to be of greater interest to interventional cardiologists than those describing a new channelopathy. So, with the explosion of papers on subjects more specific to interventional cardiology being submitted to the major cardiology journals, decisions were taken to launch EuroIntervention, Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, and JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. All have been successful and the editors have generally been more collaborative that competitive. When Patrick Serruys asked me to write in support of EuroIntervention for the listing services, I was delighted to do so. His fellows sent papers to us and ours to him. David Faxon, who started Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, asked one of my associate editors, David Williams, to become his deputy. David Williams expressed regret to leave, but the move was sensible since he had relocated to Harvard where that journal was being published. I asked Chris White, who was editor-in-chief of Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, to be an associate editor for JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions and he agreed. Yes these journals have matured together, successfully.

So the period from 2007 until now has produced a large receptacle for papers in interventional cardiology. Is it only a trash basket or are there worthy contributions that should be published? The availability of journal pages, print or electronic, has been matched by the constantly increasing supply. To cope with this volume at JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, we began publishing biweekly. Despite this, the acceptance rate remains below 10%, so there is no shortage of interesting work. This work, by the way, comes from all over the world. The golden age of publishing has been made possible by a global expansion of investigation, much of it in countries that were formally only consumers of the information but now are producers. Meanwhile, important questions about how to acquire knowledge in cost-effective ways are being asked. Prospective registries and outcomes research are augmenting and expanding knowledge from randomised trials. We have all learned a lot from systems such as those in Scandinavia and elsewhere that are able to use longitudinal comprehensive outcome data to better influence practice. In the USA and in other countries, registries such as the National Cardiovascular Data Registry are becoming more valuable as broader populations of patients with diseases, not just those with procedures, have begun to be included. The exponential explosion of investigation from China over 10 years is reflected by soaring submissions to the journals. Of course, the last 10 years have also seen dramatic developments in structural heart disease interventions so that now fully one third of all submissions address these topics.

During this 10-year period the global expansion of interventional cardiology is undeniable. Some of that is due to the educational efforts of the major societies and local organisers of educational and training programmes, but much of the levelling of expertise and availability of interventional cardiology throughout the world is due to this golden age of publishing/investigation.

As politics around the world seems to be threatened by xenophobic nationalism, perhaps the “good globalisation” of interventional cardiology could be a metaphor for progress in other areas. Since any “golden age” can only be judged in its historical context, I hope this period will be viewed as the early phase of a more complete understanding and treatment of cardiovascular disease and that the ability to disseminate the results through publishing will continue to expand.

Conflict of interest statement

S.B. King III is the Editor-in-Chief of JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.