When thinking about heart and brain reperfusion, several factors have to be taken into account: 1) the experience of the team, 2) the safety, effectiveness and availability of the selected therapy, 3) the appropriate therapeutic time window, and 4) the current evidence and clinical recommendations.

The heart

The joint EAPCI/EuroPCR Stent for Life Initiative began in 2008 and represents a highly successful model of care for patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI)1,2. Within a period of three to four years, it has been possible to develop a national STEMI network and to offer timely mechanical reperfusion (primary PCI within 12 hrs of symptom onset with maximum benefit in <3-6 hrs) to the majority of the population. Though this approach represents a seemingly simple implementation of the strongest recommendation (class I, level of evidence A) from the European Society of Cardiology clinical practice guidelines3, per se it depends on the involvement of all stakeholders, widespread enthusiasm and multidisciplinary collaboration. In simple terms, to save more lives and to improve the quality of life after an acute heart attack we have to boost the whole acute healthcare system. The optimal and fastest pathway corresponding to a relatively simple pathophysiology (plaque erosion/rupture and thrombosis in >90% of cases) consists of an early diagnosis of STEMI by the emergency medical service (EMS) and direct transportation to the nearest 24/7 cathlab. Reperfusion of the infarct-related artery within 20 to 25 minutes after arrival at the cathlab is the extraordinary beauty of primary PCI. At present, the optimal primary PCI technique comprises the transradial approach, the tailored use of manual thrombectomy, drug-eluting stent implantation and a combination of potent antithrombotic medication. The role of intracoronary imaging as well as the optimal management of patients with multivessel disease have been studied intensively4.

The brain

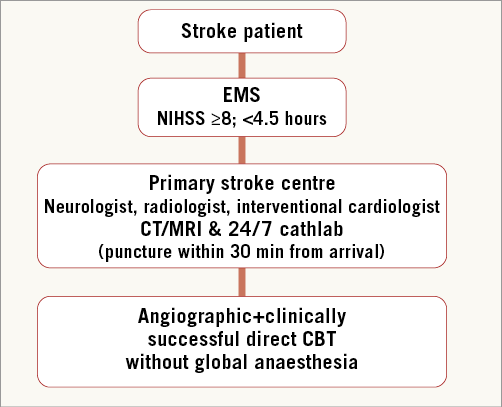

Unfortunately, the pathophysiology of stroke is different and more complex. Besides cerebral haemorrhage (15% of strokes) and lacunar cerebral infarctions, both intracranial and extracranial arteries may be affected (internal carotid, middle cerebral and posterior circulation arteries). In contrast to STEMI, the time window for administration of intravenous (i.v.) thrombolysis and ischaemic stroke reperfusion is only <4.5 hrs from symptom onset5. The pathway to reperfusion is also more complex and requires a precise multidisciplinary collaboration throughout the whole diagnostic and therapeutic process. Also, the main difference between the treatment of stroke and the STEMI fast track to cathlab is the need for neurologic and computed tomography/magnetic resonance (CT/MR) evaluation (Figure 1). Another obstacle is the current lack of evidence from randomised trials supporting catheter-based thrombectomy alone. The use of the Merci® Balloon Guide Catheter (Stryker® Neurovascular, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), the Penumbra System® (Penumbra Inc., Alameda, CA, USA), the Solitaire™ FR Revascularization Device (Covidien/ev3 Endovascular Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA), and the Trevo® Pro Retriever System (Stryker® Neurovascular) has recently been recognised as class IIa, level of evidence B in the guidelines for early management of patients with acute ischaemic stroke5. As with STEMI, neither intra-arterial thrombolysis nor the facilitated intervention (thrombolysis+mechanical reperfusion) provides better clinical outcome in comparison to simple i.v. thrombolysis5-7.

Figure 1. STEMI-like stroke pathway perspective. CT: computed tomography; EMS: emergency medical service; MR: magnetic resonance; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Interventional cardiology as part of the stroke programme

In this issue of EuroIntervention, two original papers describe the results of catheter-based thrombectomy (CBT) in ischaemic stroke patients. These publications comprise single-centre data from relatively small cohorts of patients from the Czech Republic and Turkey. The most exciting fact is that the first authors are neither neurologists nor neuroradiologists or invasive radiologists, but interventional cardiologists. Widimsky et al in their pilot experience from the prospective PRAGUE-16 study present the results of 23 patients with moderate to severe acute ischaemic stroke8. Patients were planned to be treated with direct CBT only with no previous thrombolysis within <6 hrs from the onset of typical symptoms. Nevertheless, five patients (21.7%) received thrombolysis prior to CBT. Mechanical recanalisation with three stent retriever systems (Trevo, Solitaire and Penumbra) was successful in 83% of patients after a mean of three thrombus retrieval attempts. A favourable functional clinical outcome was achieved in 48% of patients. The precise logistics of the joint programme provided by the local stroke team (interventional cardiologist, neurologist and radiologist) are very well described. Goktekin et al conducted a retrospective analysis of 38 patients treated with the Solitaire AB Neurovascular Remodeling Device (Covidien/ev3 Endovascular Inc.) by a local stroke team composed of an interventional cardiologist, neurologist, radiologist and anaesthesiologist9. Successful recanalisation was achieved in 89% of patients, and in 57.9% a good clinical outcome was observed at 90 days.

CBT was indicated within 4.5 hrs in patients with contraindication for i.v. thrombolysis, and within 4.5 to 6 hrs in patients with presence of penumbra confirmed by CTA/MRA. Though the results of CBT are promising, the common negative point of the presented local stroke programmes is the low number of treated patients. Twenty-three patients were enrolled in Prague within 16 months and 38 patients were treated in Istanbul within 24 months, making the mechanical stroke programme very challenging, requiring further analysis and improvements. Randomised trials comparing i.v. thrombolysis versus direct CBT are greatly needed.

Heart & brain, brain & heart questions

Q1: What can we - interventional cardiologists - offer to stroke patients?

1. A STEMI network with 24/7 cathlabs.

2. Highly experienced interventional teams.

3. Fully equipped cathlabs offering life-saving procedures and resuscitation.

4. High-quality X-ray equipment.

5. Excellent collaboration with EMS and routine use of telemedicine.

Q2: What do we - interventional cardiologists - have to learn to take an effective part in the stroke team?

1. Flow grading systems: Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (TICI)10 and Mori11 classification.

2. Stroke severity: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score 0-42.

3. Cerebral anatomy/function by CT/MR.

4. Dedicated diagnostic and therapeutic invasive techniques and tools.

5. Modified Rankin scale (mRS) score 0-612.

Conclusion

Cardiovascular mortality, acute heart attack (especially STEMI) and ischaemic stroke represent the leading causes of death worldwide. Ischaemic stroke in particular is the most common cause of acquired disability and the third most frequent cause of death13. The establishment of a STEMI network, which has been supported in many countries by the Stent for Life (SFL) Initiative, may be followed by a STEMI-like network for stroke patients. The joint stroke programme, introduced by Widimsky and Goktekin8,9, fully accomplishes the SFL motto “Working together. Saving lives”.

Conflict of interest statement

P. Kala receives consultancy fees from Boston Scientific.