Abstract

Endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) has evolved from a single-indication test for the early diagnosis and monitoring of heart transplant rejection to the gold-standard technique to reach a definite and aetiological diagnosis in different cardiac disorders such as myocarditis and cardiomyopathies. It is currently considered a fundamental tool in the diagnostic workup of unexplained acute heart failure with haemodynamic compromise. For interventional cardiologists, EMB represents a unique opportunity to bridge invasive diagnostics with personalised care. By embracing technological advancements, integrating EMB with non-invasive modalities, the field advances towards more precise and effective management of complex cardiac conditions. However, safety remains a concern when performing EMB; indeed, although rare, major complications occur in about 1-5% of cases. Correct indication for the procedure and specific expertise to minimise the risk of complications are fundamental to obtain an acceptable risk/benefit profile. Therefore, this review examines the contemporary use of EMB from the perspective of interventional cardiologists to provide a practical resource for clinical practice and to better understand when and how to perform both right and left ventricular EMB in current practice.

Percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) has evolved from a single-indication test for the early diagnosis and monitoring of heart transplant rejection to the gold-standard technique to reach a definite and aetiological diagnosis in different cardiac disorders such as cardiomyopathies, myocarditis, inflammatory cardiomyopathies, storage and infiltrative myocardial disorders, etc.

Throughout the years, we have also witnessed improvements in EMB equipment, integration with multimodality imaging, tissue processing, and analysis techniques. However, safety remains a concern when performing EMB; indeed, although rare, major complications occur in about 1-5% of cases123. Major complications include cardiac perforation, thromboembolism, valvular trauma, sustained ventricular arrhythmias, and vascular complications, influenced by the clinical setting and the operator’s experience4567. Correct indication for the procedure and specific expertise to minimise the risk of complications are fundamental to obtain an acceptable risk/benefit profile.

Selection of the best candidates for EMB

In the era of advanced multimodality imaging, EMB continues to offer unique insights into myocardial pathology that cannot be achieved through non-invasive methods and therefore remains an important tool for diagnosing heart diseases and orienting clinical management and treatment strategies8. Indications for EMB in clinical practice have been based mostly on heterogeneous expert opinions and empirical decisions238910. Unexplained acute heart failure (HF) with haemodynamic compromise or ventricular arrhythmias/conduction disorders of unknown origin, cardiomyopathies, clinically suspected acute myocarditis (AM) or cardiac sarcoidosis (CS), storage and infiltrative diseases, and cardiotoxicity represent challenging scenarios in which EMB can be considered (Table 1).

In the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) HF Guidelines, EMB is indicated in “rapidly progressive HF despite standard therapy, when there is a clinical pretest probability of a specific diagnosis requiring precise treatments, which can be confirmed only in myocardial samples” (Class IIa recommendation)10. Therefore, EMB is expected to be highly informative when indicated on clinical grounds to (a) confirm a clinically suspected diagnosis and (b) provide information relevant for patients’ management.

An exemplar case is represented by patients with suspected AM presenting with cardiogenic shock or acute HF with ventricular dysfunction and/or severe rhythm disorders. Indeed, AM is a reversible model of inflammatory cardiomyopathy that may be treated with immunosuppressive therapy in the absence of contraindications2. The characterisation of inflammatory cells in the myocardium is essential for differentiating various histological forms of inflammation. This differentiation is particularly important for conditions associated with poor outcomes, such as giant cell myocarditis, eosinophilic myocarditis, and granulomatous myocarditis (resulting in CS), where timely initiation of immunosuppressive therapy is recommended to improve survival.

Moreover, immune checkpoint inhibitor-related AM is a challenging complication of cancer immunotherapy. EMB may be incorporated for early and accurate diagnosis, which is essential for proper treatment and oncological decisions11, especially when cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging results are inconclusive.

In patients with suspected fulminant myocarditis (FM) supported by venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO), EMB can achieve a diagnostic yield of up to 78% for identifying the cause of acute HF, albeit with a significantly increased risk of complications512.

EMB may be indicated in the diagnostic workup of unexplained cardiomyopathies with a hypertrophic or restrictive phenotype and inconclusive non-invasive results that pose a diagnostic challenge between sarcomeric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and other conditions’ phenocopies, such as cardiac amyloidosis (CA). Non-invasive diagnosis of transthyretin CA can be achieved in the presence of grade 2-3 cardiac uptake of bone tracers and no biochemical evidence of monoclonal proteins in serum and/or urine. If a monoclonal protein is detected, histological confirmation of amyloid deposition in EMB or extracardiac samples is required to confirm amyloid light chain (AL)-amyloidosis.

EMB gains particular relevance in (i) acute cardiac settings, refractory to standard therapies; (ii) patients unable to undergo non-invasive evaluations (e.g., when CMR imaging is contraindicated or not feasible); (iii) surveillance purposes, such as detecting rejection in heart transplant recipients; and (iv) very select cases of chronic, haemodynamically stable patients with inconclusive non-invasive findings and suspected inflammatory diseases (e.g., persistent or recurrent elevation of serum troponin, frequent ventricular arrhythmias, or new-onset systolic dysfunction) or cardiomyopathy “phenocopies”13.

EMB is not indicated in certain scenarios where the expected diagnostic and therapeutic benefits are limited, leading to an unacceptable risk/benefit balance, for example, in first presentations of low-risk AM, characterised by chest pain, normal ventricular function, absence of ventricular arrhythmias, and rapid resolution of electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities. Furthermore, the EMB approach is not indicated for friable intracardiac masses with high embolic risk, such as left-sided tumours or typical cardiac myxomas, nor for mobile and small protruding structures that make the procedure technically difficult and unsafe.

Finally, when performing EMB, a Heart Team discussion, or at minimum, a collegial discussion between the clinical cardiologist and the interventional cardiologist is essential and should be clearly documented in the patient’s medical records. This approach supports appropriate patient selection and shared decision-making, particularly in complex or high-risk cases. Prior to the procedure, a detailed informed consent must be obtained from every patient. This consent should clearly explain the purpose of the procedure, its potential complications (including the risk of requiring emergency cardiac surgery), and the individualised risk/benefit profile.

Table 1. Clinical indication to endomyocardial biopsy according to current recommendations from European and international scientific societies.

| Authors | Year | Scientific associations | Document | Clinical indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seferovich P et al3 | 2021 | Trilateral cooperation: HFA of ESC, HFSA, JHFS | Consensus document containing updated indications for EMB in nine clinical scenarios | Suspected fulminant/acute myocarditis with acute HF and/or rhythm disorders or suspected myocarditis in haemodynamically stable patients |

| DCM with new-onset HF and LV dysfunction, non-responsive to standard medical therapy | ||||

| Unexplained hypertrophic or restrictive myocarditis | ||||

| Unexplained ventricular arrhythmias, high-degree AV and/or syncope | ||||

| Autoimmune disorders with progressive HF refractory to treatment | ||||

| Suspected ICI-mediated cardiotoxicity | ||||

| MINOCA/Takotsubo syndrome with progressive HF and LV dysfunction | ||||

| Cardiac tumours | ||||

| HTx rejection status monitoring | ||||

| McDonagh T A et al10 | 2021 | ESC | Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic HF | EMB should be considered in rapidly progressive HF despite standard therapy, when there is a clinical pretest probability of a specific diagnosis requiring precise treatments, which can be confirmed only in myocardial samples (Class IIa). |

| EMB with immunohistochemical quantification of inflammatory cells remains the gold standard investigation for the identification of cardiac inflammation. | ||||

| EMB may confirm the diagnosis of autoimmune disease in patients with DCM and suspected giant cell myocarditis, eosinophilic myocarditis, vasculitis, and sarcoidosis. | ||||

| EMB may help for the diagnosis of storage diseases, including amyloid or Fabry disease, if imaging or genetic testing does not provide a definitive diagnosis. | ||||

| EMB might be considered in HCM if genetic or acquired causes cannot be identified. Careful assessment of the risk-benefit ratio of EMB should be systematically evaluated. | ||||

| Arbelo E et al9 | 2023 | ESC | Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies | In patients with suspected cardiomyopathy, EMB should be considered to aid in diagnosis and management when the results of other clinical investigations suggest myocardial inflammation, infiltration, or storage that cannot be identified by other means. |

| EMB should be considered in patients with RCM to exclude specific diagnoses (including iron overload, storage disorders, mitochondrial cytopathies, amyloidosis, and granulomatous myocardial diseases) and to diagnose restrictive myofibrillar disease caused by desmin variants. | ||||

| Endomyocardial biopsy should be reserved for specific situations where its results may affect treatment after careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio. | ||||

| Drazner MH et al2 | 2024 | ACC | Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Strategies and Criteria for the Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis | In patients with certain presentations – typically those with reduced ventricular function, deranged haemodynamics/symptomatic HF, or electrical instability – an EMB is warranted to diagnose specific conditions that require aetiology-directed therapies, including immunosuppressive agents. |

| EMB is recommended in clinical scenarios where the prognostic and diagnostic value of the information gained outweighs the procedural risks. | ||||

| AV: atrioventricular; DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy; EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HF: heart failure; HFA: Heart Failure Association; HFSA: Heart Failure Society of America; HTx: heart transplant; ICI: immune checkpoint inhibitor; JHFS: Japanese Heart Failure Society; LV: left ventricular; MINOCA: myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary arteries; RCM: restrictive cardiomyopathy | ||||

Right or left ventricular EMB?

Traditionally, EMB has been performed from the right ventricle (RV) using a central venous access. Over the years, left ventricular (LV) EMB has been established as an alternative approach to RV EMB in light of its ability to yield more informative results than RV biopsy in some specific contexts67.

LV EMB has been shown to be both feasible and safe; however, compared to RV EMB, it may carry a slightly higher risk of local haematoma and the potential for transient cerebral ischaemia6. The LV has thicker walls compared to the RV, and this is considered the reason for the lower rates of cardiac perforation, which is the most challenging and life-threatening complication of LV EMB67814.

The diagnostic performance of single-chamber (i.e., LV or RV biopsy) compared with biventricular biopsy has been investigated by a few studies. In a cohort of 755 patients with suspected myocarditis or non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, biventricular EMB provided diagnostic results more frequently than single-chamber EMB7. Chimenti et al6 evaluated more than 4,000 patients undergoing biventricular EMB or selective LV or RV EMB. The diagnostic performance of RV and LV EMB varied significantly based on the presence of structural or functional abnormalities. When the LV was exclusively or predominantly affected, the diagnostic yield of LV EMB was 97.8% and that of RV EMB was 53%. When the RV was involved along with the LV, the diagnostic yield of RV EMB increased to 96.5% as opposed to that of LV EMB, which was unchanged at 98.1%6. These findings suggest that LV EMB is the most informative approach when the LV is the diseased chamber and the RV is relatively unaffected, while RV EMB is preferred when there is evidence of structural or functional RV involvement, as it is equally informative and carries a lower risk of complications6.

In summary, when posing indications for EMB, a number of factors should be considered by interventional cardiologists to increase the chances of yielding diagnostic results313. These factors include (a) the clinical query; (b) the most diseased areas of the heart; and (c) the nature of the suspected cardiac process (focal vs diffuse).

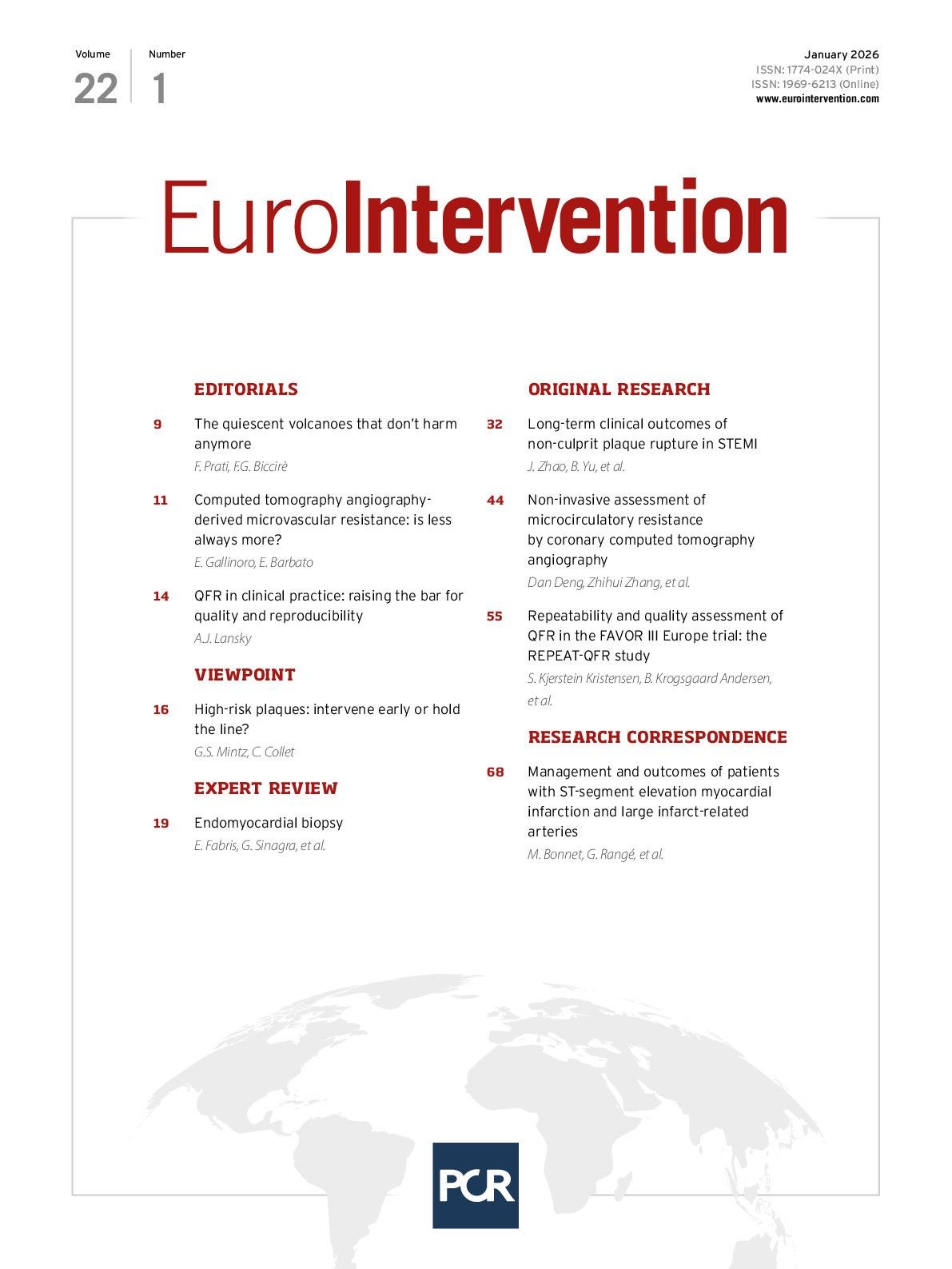

In clinical practice, RV EMB is the preferred strategy in most patients with clinical suspicion of diffuse cardiac diseases, such as CA, Anderson-Fabry disease, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, unexplained restrictive cardiomyopathy, or AM with biventricular structural and/or functional abnormality8. LV EMB may be preferred in patients with suspected AM with primary LV involvement, unexplained dilated cardiomyopathy with isolated LV involvement, or CS. In focal diseases, such as CS, biventricular EMB and the collection of specimens from multiple cardiac sites should be considered, as sampling error is the major drawback of EMB in this setting (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1. Different endomyocardial biopsy approaches in individual patients. Ab: antibody; CR: Congo Red; EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; EPS: electrophysiological study; H&E: haematoxylin and eosin staining; HLA-DR: human leukocyte antigen – DR isotype; IHC: immunohistochemistry; LV: left ventricle; PAS: periodic acid-Schiff; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; RV: right ventricle

Table 2. Right versus left ventricular endomyocardial biopsy.

| Choice of ventricular chamber to approach with endomyocardial biopsy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factors to be considered | Clinical query | |

| Most diseased areas of the heart | ||

| Nature of suspected cardiac process (focal vs diffuse) | ||

| Right ventricular EMB | Left ventricular EMB | |

| First choice in case of biventricular involvement | First choice in LV diseases with preserved RV | |

| Operator experience requirement | Less technically demanding | More technically demanding |

| Cardiac perforation | Higher risk compared to LV EMB, but less life-threatening | Lower risk compared to RV EMB, but more life-threatening |

| Access site complications | Venous access complications (e.g., haematoma) | Arterial access complications (e.g., pseudoaneurysm) |

| Risk of embolisation | Lower; pulmonary embolism | Slightly higher; stroke or systemic embolism |

| Conduction system injury | Higher risk of atrioventricular block | Lower risk of atrioventricular block |

| Ventricular arrhythmias | Usually transient | Usually transient |

| Valve damage | Potential tricuspid valve damage | Potential mitral valve damage |

| Specimen analysis | Adequate for most diagnoses | Can be superior for certain pathologies |

| Key points | ||

| Generally safer and suitable for routine EMB, especially in settings with limited technical expertise | Higher risk due to arterial access and the potential for life-threatening cardiac perforation Often provides superior tissue samples for certain pathologies but requires greater technical skill and experience | |

| EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; LV: left ventricular; RV: right ventricular | ||

Technical and procedural steps in the cath lab

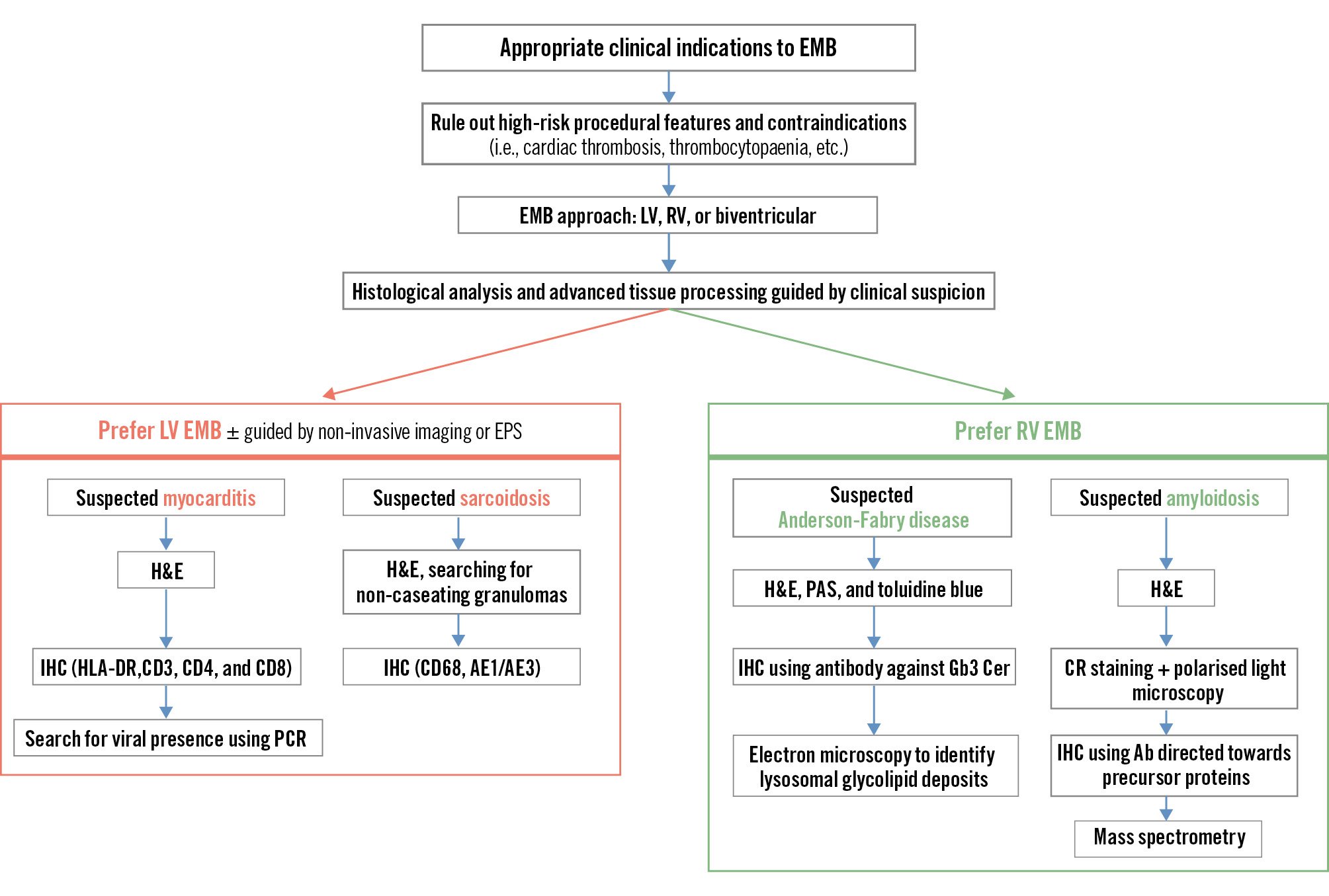

Nowadays, there are several bioptomes (Figure 2), which are available in different lengths and French sizes, with preshaped and straight tips. The currently available bioptomes are flexible devices and are positioned with the aid of a long sheath (Figure 3).

Before the procedure, the presence of a ventricular thrombus or a low platelet count (<50,000/mm3) must be assessed, as these may represent contraindications to EMB. Oral anticoagulants must be discontinued. In order to reduce potential arterial or venous access site complications, ultrasound-assisted puncture of access sites is recommended15. The patient’s heart rhythm and invasive blood pressure should be continuously monitored, with defibrillator patches applied, as sustained ventricular arrhythmias may occur. EMB procedural steps are reported in Table 3.

For LV EMB, if possible, cardiac surgery standby should be activated. After either RV or LV EMB, each patient is monitored for a minimum of 15 minutes in the cath lab facility while transthoracic echocardiography is performed to detect any significant pericardial effusion, or new/worsening mitral or tricuspid regurgitation.

Figure 2. Bioptomes and characteristics. Fr: French

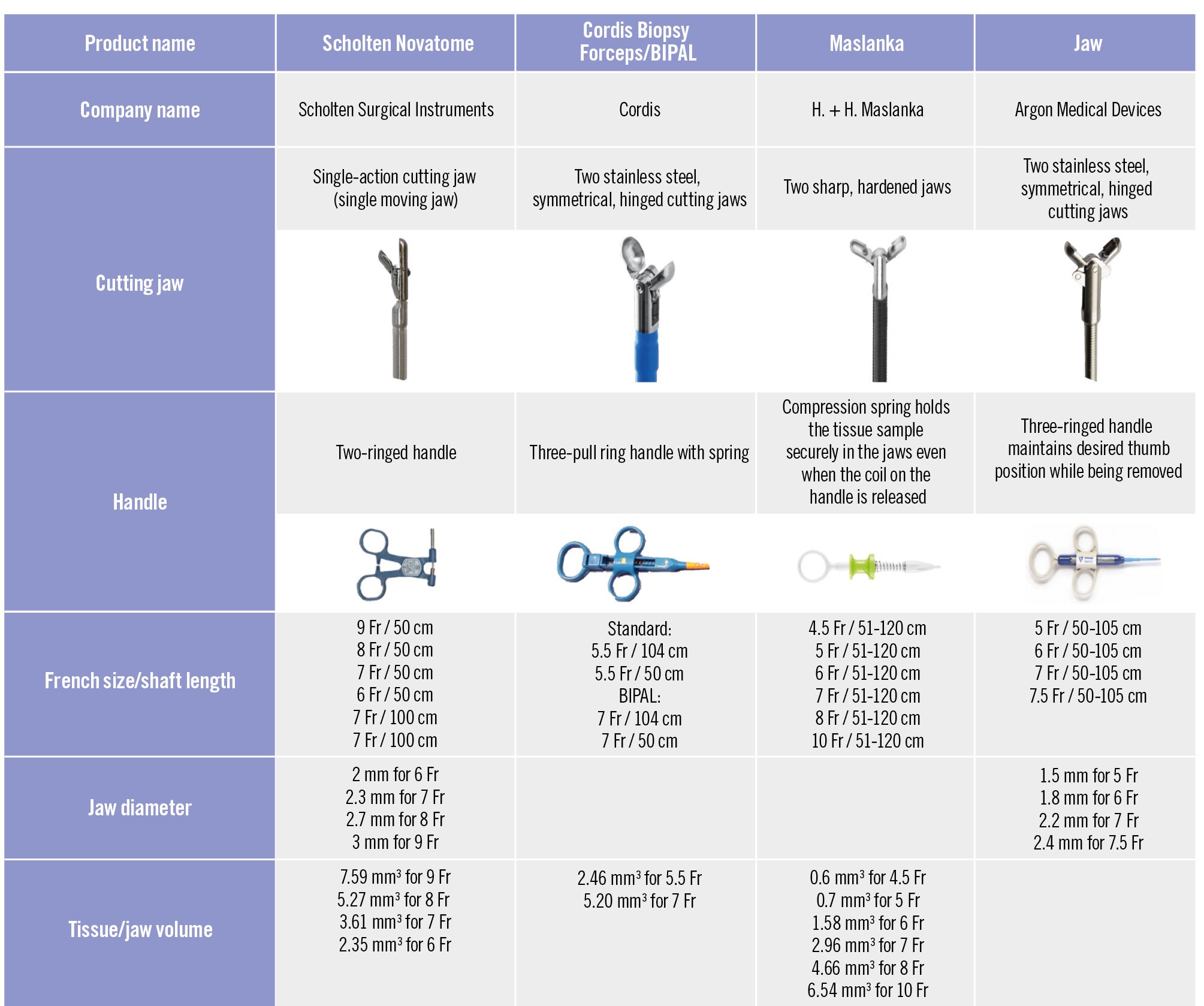

Figure 3. Left ventricular EMB. Example of a left ventricular endomyocardial biopsy. A) Fluoroscopic left anterior oblique (LAO) projection of a long sheath in the ventricle over a pigtail catheter pointing towards the lateral wall. B) Fluoroscopic right anterior oblique (RAO) projection of a long sheath positioned in the ventricle over a pigtail catheter in the midventricular chamber pointing towards the anterior wall. These two complementary views facilitate the identification of the tissue sample site. C) Fluoroscopic views of the endomyocardial biopsy procedure in the anterolateral wall. The circled images highlight the long sheath over a pigtail catheter (A, B) and the bioptome exiting from the long sheath (C). EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; LV: left ventricular

Table 3. Procedural steps for endomyocardial biopsy.

| Basic procedural steps for endomyocardial biopsy |

|---|

| Continuously monitor heart rhythm and invasive blood pressure, with defibrillator pads applied |

| Carry out ultrasound-assisted vascular access puncture and positioning of the introducer |

| If performing a left ventricular EMB, administer intravenous heparin to achieve an ACT >200 seconds |

| Insert a long sheath (preferable to protect valvular structures) into the ventricular chamber over a pigtail catheter, advanced over a 0.035" guidewire |

| Perform ventriculography through the pigtail catheter to facilitate long sheath positioning |

| Remove the pigtail, aspirate and flush the long sheath, and check ventricular pressure (precaution: avoid injecting contrast directly from the sheath if ventricular pressure is not visualised, due to the risk of endocardial injury) |

| Confirm position of the tip of the long sheath by fluoroscopy projections |

| Insert the bioptome, with a prebent tip, into the long sheath |

| Open the forceps inside the distal segment of the long sheath and keep the jaws open until myocardial contact |

| Close the jaws upon light resistance (ventricular ectopy or non-sustained VT may occur), perform closure and withdrawal in one smooth motion |

| Keep the jaws closed while retracting the bioptome into the sheath, to avoid specimen loss or embolisation |

| Remove the bioptome, aspirate and flush the long sheath, and check ventricular pressure |

| Repeat bioptome insertion to obtain a minimum of 5 tissue samples from different sites |

| Perform focused echocardiography to detect new pericardial effusion or valvular damage |

| ACT: activated clotting time; EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; VT: ventricular tachycardia |

Left ventricular EMB

LV EMB is usually performed via the femoral artery; however, advances in sheathless guide technology (e.g., 7.5 Fr EauCath [ASAHI Intecc] in combination with a 5.4 Fr Maslanka bioptome [H. + H. Maslanka]) can permit LV EMB through the radial artery, an emerging alternative access for LV EMB1617. Indeed, radial artery access has been found to be non-inferior to transfemoral artery access regarding major complications18 and may result in fewer access site bleedings compared to femoral access19. Femoral access, however, still remains the most common approach for LV EMB, and the long-sheath technique is predominantly used for semiflexible bioptomes to avoid repeated exposure of the valve leaflets to the bioptome.

Intravenous heparin is given to reach an activated clotting time >200 s to reduce the risk of systemic embolism. A long sheath with a straight tip is introduced in the ventricle over a pigtail catheter, which is advanced over a 0.035” wire under fluoroscopy guidance. At this stage, performing a ventriculography through the pigtail catheter can facilitate positioning (Figure 3). Injecting from the long sheath or a guiding catheter should be avoided if the LV pressure is not visualised, because of the risk of endocardial damage. A mid-left ventricular cavity position of the tip of the sheath is confirmed in right anterior oblique (RAO) and left anterior oblique (LAO) projections to avoid the apex and remain far from the valvular apparatus (Figure 3); additional angiographic views can be used for the specific site of sample collection. The pigtail catheter is then removed, the sheath is flushed, ventricular pressure is checked, and the bioptome is introduced.

The bioptome is frequently bent at its distal part to enhance flexibility and reduce the risk of perforation. The forceps should be already in the “open” position inside the distal segment of the long sheath and must remain open until they make contact with the ventricular wall. The bioptome forceps are closed when a slight resistance is sensed by the operator; the jaws should be firmly closed to obtain a tissue specimen, and closing of the jaws and withdrawal of the bioptome should be performed in a single motion. Ventricular beat or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia is common while the bioptome is in contact with the myocardium. During the retraction of the bioptome into the long sheath, it is crucial to keep the jaws in the closed position to retain the specimen and prevent its loss and embolisation into the bloodstream. The bioptome is then removed from the sheath, and the sheath is aspirated and flushed to prevent air or tissue embolism. A successful procedure should provide at least 5 samples taken from different sites for histological evaluation, immunohistochemistry and molecular/viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analyses.

Right ventricular EMB

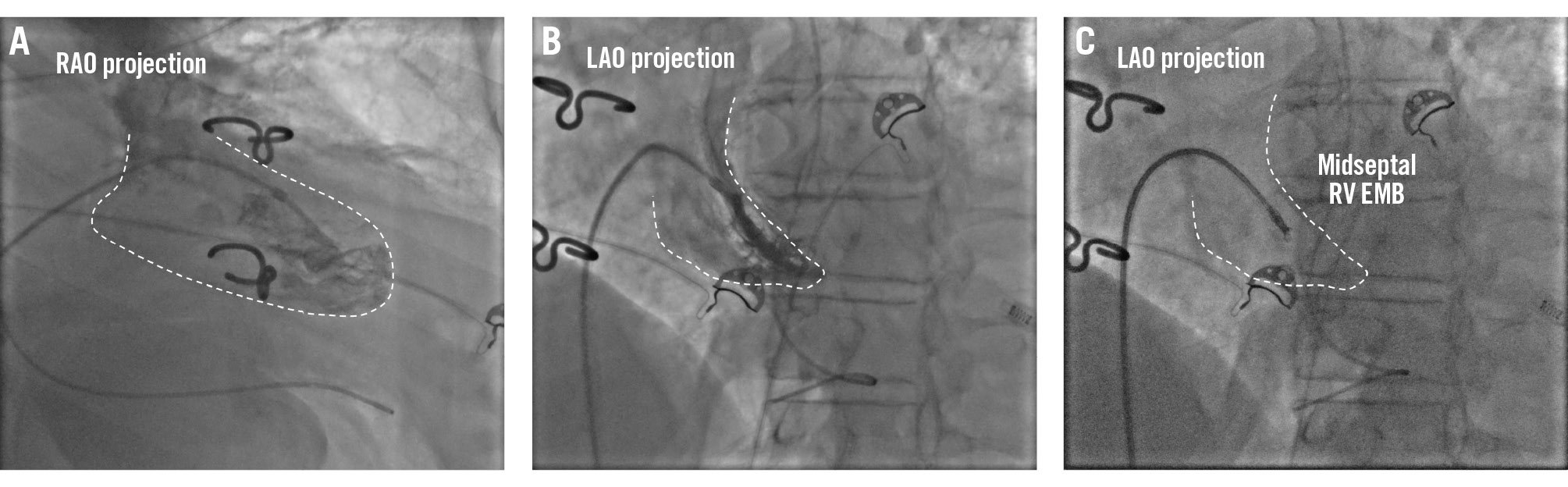

RV EMB is performed via the jugular, femoral, or brachial veins. For RV EMB sampling, the administration of heparin is not mandatory. In cases of an enlarged right atrium or an unfavourable angle for right ventricular access via the femoral vein, switching to jugular access or using steerable guiding catheters should be considered to facilitate the procedure. For RV EMB, the RV is reached through the tricuspid valve using the posteroanterior and the RAO projections, which is typically set at 30°. The RAO view provides a clear view of the right ventricular outflow tract and the right ventricular free wall to determine the mid-RV, apical, or RV outflow tract position, but the LAO 40° projection is most commonly used to guide tissue sampling from the ventricular septum (Figure 4). This projection provides a profile view of the interventricular septum (Figure 4), which is the preferred site for RV EMB to minimise the risk of injury to tricuspid valve apparatus and to the RV free wall with subsequent perforation. However, due to significant interindividual variability in cardiac long-axis orientation, it is important to adapt the fluoroscopy projections for each patient. Avoiding biopsy samples too close to the outflow tract is important as the procedure can damage the right bundle branch. In patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB), a temporary pacemaker should be considered or kept readily available because of the risk of complete atrioventricular (AV) block. An RV angiogram can be performed to identify the septum, and also transthoracic or intracardiac echocardiography can confirm bioptome positioning across the RV septum. Moreover, if a computed tomography scan is available, patient-specific computed tomographic fluoroscopic projections can be predicted20.

Figure 4. Right ventricular EMB. Example of a right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy. A) Fluoroscopic right anterior oblique (RAO) projection of a long sheath positioned in the mid-right ventricle over a pigtail catheter. B) Fluoroscopic left anterior oblique (LAO) projection of a long sheath in the right ventricle over a pigtail catheter and the long sheath pointing towards the right ventricular septum. These two complementary views facilitate the identification of the tissue sample site. C) Fluoroscopic views of the endomyocardial biopsy procedure in the mid-right ventricular septum. EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; RV: right ventricular

Potential integration with multimodality imaging

The use of imaging in EMB guidance has two advantages: on the one hand, periprocedural imaging can be used to identify sites of myocardial disease towards which to direct EMB; on the other hand, procedural imaging performed simultaneously with fluoroscopy can improve the accuracy of EMB3. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging combined with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) improves EMB diagnostic accuracy in CS by integrating functional and anatomical data to better target suspicious biopsy sites21. However, in the setting of myocarditis, data on the utility of preprocedural CMR are contrasting722. The limited concordance between CMR and EMB supports their use as complementary tools in the diagnostic evaluation of the disease.

As regards procedural imaging, it is worth mentioning the potential role of electroanatomical mapping (EAM)-guided EMB. EAM-guided EMB has emerged as a safe method which might improve the sensitivity and specificity of EMB as compared with conventional fluoroscopy-guided biopsy, as low-voltage areas align with histological abnormalities in the myocardium2324.

While determining which patients will benefit most from EAM-guided EMB is challenging, this approach seems particularly attractive for cardiomyopathies with segmental or patchy myocardial involvement, such as CS24. The utility of EAM-guided EMB in AM may be limited, as low-voltage areas tend to correlate with late gadolinium enhancement but not with myocardial oedema25. However, indications for EAM-guided EMB extend beyond CS, encompassing different myocardial disorders presenting with arrhythmias2627. Many electrophysiologists perform mapping-guided EMB, which is not technically more complex than other electrophysiological procedures, compared with standard EMB; however, it is a time-consuming procedure due to the need for detailed mapping and precise navigation to the target biopsy sites, and its cost may limit its availability in resource-constrained settings.

Role of EMB in patients presenting with severe acute heart failure and cardiogenic shock

EMB plays a critical role in patients with non-ischaemic severe acute heart failure and/or cardiogenic shock and suspected FM by enabling the identification of underlying causes, and it helps guide targeted treatments by providing histological diagnoses.

In adult patients with suspected FM, early EMB was associated with better 1-year outcomes4, while the absence of EMB in those requiring mechanical support correlated with worse prognosis28, likely due to delayed diagnosis and treatment. However, EMB remains largely underutilised2930, probably due to the perceived potential for severe complications in this setting, including cardiac tamponade5. Patients with clinically suspected FM should ideally be referred to specialised centres that have experienced operators for performing EMB as well as access to temporary mechanical circulatory support.

Case examples

Case 1

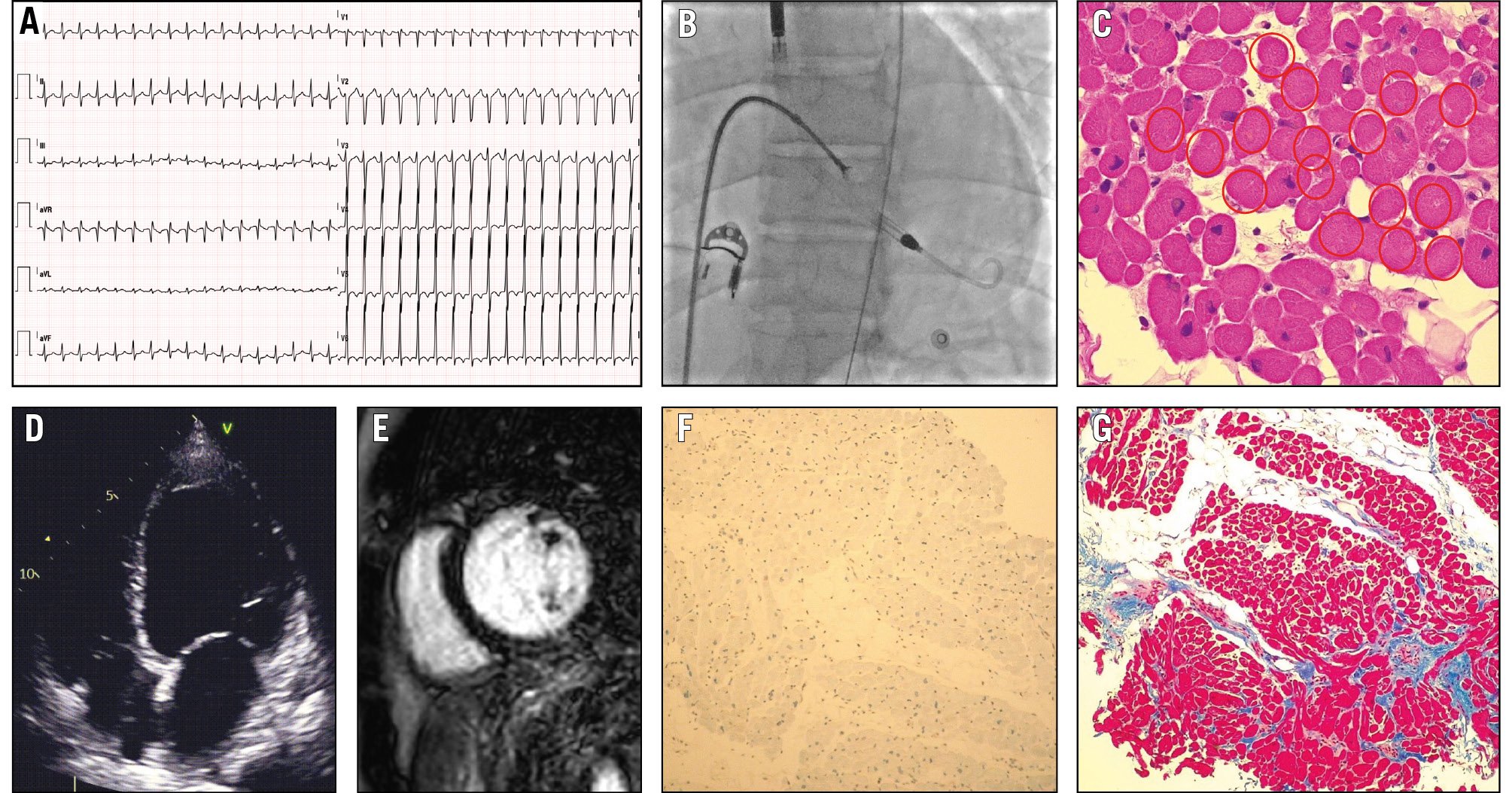

A 32-year-old male with a 1-month history of palpitations following an upper respiratory infection presented to the emergency department with asthenia, worsening dyspnoea, and epigastric pain. Admitted to the coronary intensive care unit for cardiogenic shock and multiorgan failure, ECG (Figure 5) showed atrial tachycardia at 200 bpm, and echocardiography revealed biventricular dysfunction, severe LV dilation (indexed LV end-diastolic volume [LVEDVi] of 117 mL/m2), and an ejection fraction (EF) of 12%. After transoesophageal echocardiography and initial sinus rhythm restoration via electrical cardioversion, recurrent tachycardia episodes caused further instability. Due to worsening haemodynamics, Impella CP (Abiomed) support was initiated. The coronary angiogram was normal, and an RV EMB was performed (Figure 5) which showed an absence of myocardial inflammation but did reveal early fibrosis, consistent with dilated cardiomyopathy. As instability persisted, VA-ECMO was added. During Impella+ECMO (ECMELLA) support, successful atrial arrhythmia ablation led to clinical improvement. Both devices were removed after 9 days. CMR imaging confirmed LV dilation, an EF of 21%, and non-specific findings (Figure 5). Medical therapy was started and optimised. At 4 months, EF improved to 38%; after 1 year, LV volume (LVEDVi 66 mL/m2) and EF (55%) normalised. Genetic analysis showed a pathogenic titin (TTN) mutation.

The patient’s management focused on haemodynamic support and addressing the underlying cause of ventricular dysfunction, necessitating a precise aetiological diagnosis with EMB. EMB ruled out active myocardial inflammation and pointed towards a cardiomyopathy diagnosis. Persistent atrial tachycardia was likely a trigger for ventricular dysfunction and worsening haemodynamics. Transcatheter ablation led to clinical stabilisation.

Figure 5. A case of cardiogenic shock in a patient with cardiomyopathy diagnosed by EMB. A) Electrocardiogram of a 32-year-old male admitted with cardiogenic shock, showing atrial tachycardia (heart rate of 200 beats per minute) and negative T waves in the anterolateral leads. B) Right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy was performed during mechanical circulatory support with the Impella device. C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining revealing the absence of myocardial inflammation, the absence of nuclei in many cells (highlighted with red circles), dysmetric and dysmorphic nuclei, and cells with a reduced contractile component. D) Echocardiogram demonstrating left ventricular dilation, with a left ventricular end-diastolic volume index of 117 millilitres per square metre. E) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating basal inferior mild late enhancement after gadolinium administration. F) Immunohistochemical analysis showing no activation of human leukocyte antigen. G) Azan-Mallory staining indicating early fibrosis, consistent with the diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy. EMB: endomyocardial biopsy

Case 2

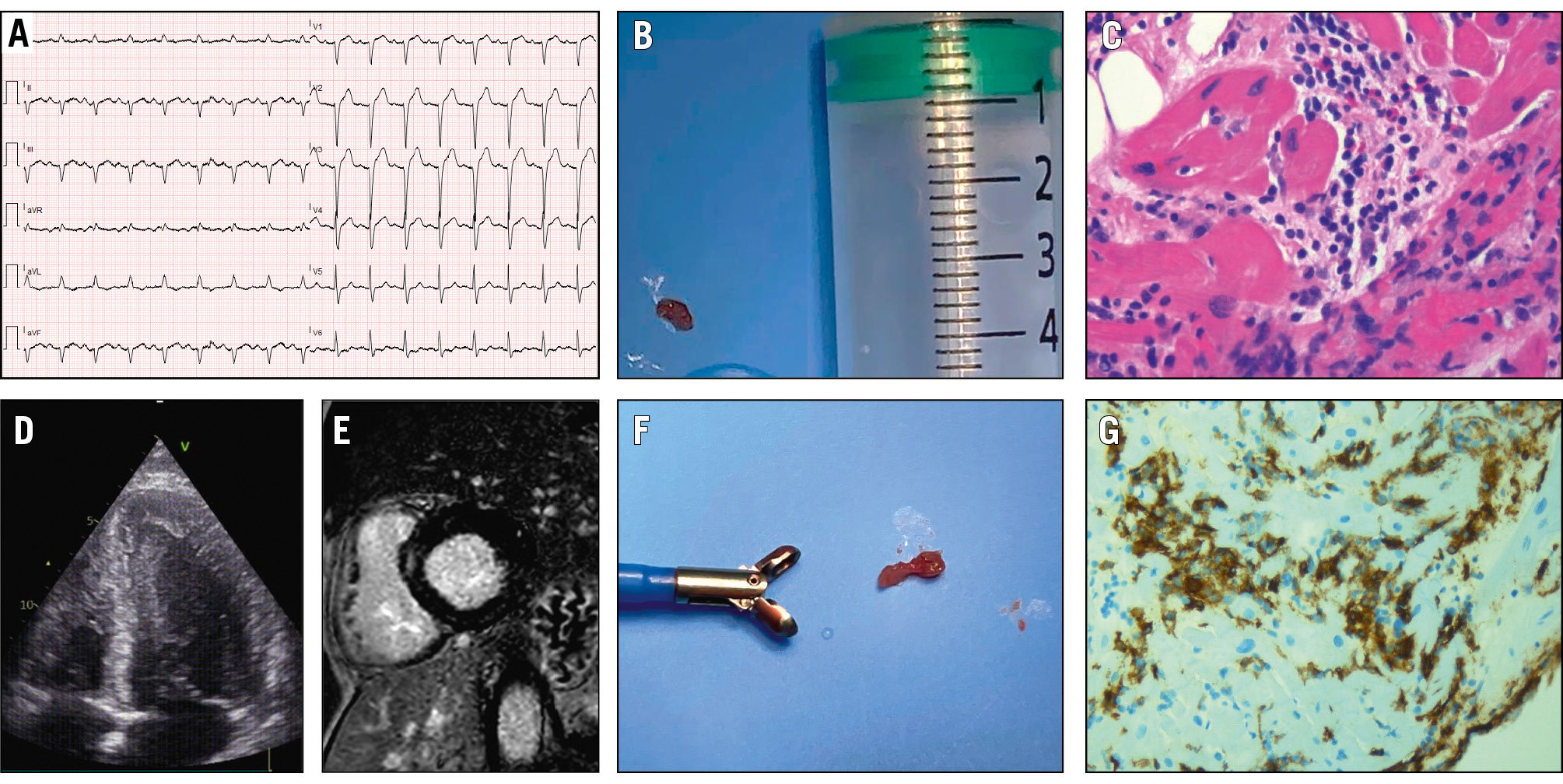

A 40-year-old male was admitted with cardiogenic shock and multiorgan failure following retrosternal pain and flu-like symptoms. The ECG showed sinus tachycardia with LBBB (Figure 6), and the echocardiogram revealed moderate LV dilation and severe LV dysfunction (EF 25%), and moderate mitral regurgitation. The coronary angiogram was normal. He received an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) and a temporary pacemaker for the occurrence of AV block. LV EMB showed severe inflammation dominated by natural killer (NK) CD16+ lymphocytes (Figure 6); viral PCR was negative. Immunosuppressive therapy with cortisone and azathioprine was initiated. He was discharged after 15 days with a normal EF. CMR imaging showed mild LV dilation, EF 53%, and midseptal intramural anterior late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). LV EMB in this case confirmed active myocarditis, which could not be definitively diagnosed through non-invasive methods alone in this unstable setting. EMB identified the inflammatory cell type and excluded viral infection via PCR, guiding effective immunosuppressive therapy and leading to the patient’s recovery.

Figure 6. A case of cardiogenic shock in a patient with myocarditis diagnosed by EMB. A) Electrocardiogram of a 40-year-old male admitted with cardiogenic shock, showing sinus tachycardia and left bundle branch block. B, F) Myocardial tissue specimens obtained from a left ventricular endomyocardial biopsy. C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining revealing severe inflammatory infiltrates. D) Echocardiogram demonstrating left ventricular dilation with a “smoke” sign, indicative of low ejection fraction. E) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating anterior midseptal intramural late gadolinium enhancement. G) Immunohistochemical analysis showing a dominant population of natural killer (NK) CD16+ lymphocytes. EMB: endomyocardial biopsy

Advances in EMB tissue processing and analysis techniques

Back in the 1980s, the diagnosis of myocarditis was based on the Dallas criteria31. The low sensitivity of these criteria was overcome by immunohistochemical analysis, which provides essential information on the presence, type, and degree of inflammatory cells within the myocardium, using stains to detect immune activation (i.e., human leukocyte antigen – DR isotype [HLA-DR]) and specific antibodies targeting T cells (i.e., CD3, CD4 and CD8) and macrophages (i.e., CD68). However, universally accepted definitions and criteria are still under discussion within the cardiopathologist community32. Nevertheless, nowadays, histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses, combined with viral genome presence research via PCR analysis, represent the cornerstones in addressing immunomodulation strategies33. While immunosuppression is indicated in severe forms of myocarditis, i.e., giant cell myocarditis, to improve outcomes, especially if initiated early343536, there is no conclusive evidence of a survival advantage in lymphocytic myocarditis. However, immunosuppression is effective and safe when tailored to the patient and administrated in virus-negative EMB37.

In recent years, major advances have been made in tissue processing in the field of systemic amyloidosis. Amyloid deposits can be identified histologically by apple-green birefringence under crosspolarised light after Congo Red staining or by non-branching 10 nm fibrils using electron microscopy. Amyloid typing is typically performed using antibody-based methods (e.g., immunohistochemistry) to detect specific precursor proteins such as transthyretin (TTR), light chains, or apolipoproteins. Sophisticated techniques such as immunoelectron microscopy and mass spectrometry have emerged as validated and highly specific methods, with mass spectrometry being considered the preferred technique for amyloid typing38. Accurate characterisation of amyloid type is crucial for guiding treatment, as cardiac light chain amyloidosis requires urgent chemotherapy, while cardiac TTR amyloidosis can benefit from targeted therapies that slow disease progression and improve survival.

Future perspectives

The role of EMB in clinical practice is poised to evolve in response to technological advancements and the growing focus on precision medicine. The integration of EMB with advanced imaging modalities (such as CMR imaging, scintigraphy, and PET) is paving the way for hybrid diagnostic protocols.

Additionally, integrating bioptome technology with advanced real-time imaging guidance such as electrophysiological mapping systems may enable targeted biopsies of pathological regions, improving diagnostic precision39. The future of EMB lies not only in improving procedural techniques but also in realising its full potential to enhance cardiovascular care, combining advanced molecular and genetic analyses to tailor therapies more effectively. In select cases, combining tissue analysis with genetic testing may provide pathophysiological insights into specific cardiomyopathies (e.g., for hot phases of cardiomyopathy)40, facilitating personalised therapeutic decisions. Moreover, gene therapy shows promise for treating inherited cardiomyopathies, and EMB could be crucial for evaluating therapeutic efficacy, assessing cardiomyocyte transduction, evaluating myocardial histological features, and measuring protein expression41.

Incorporating EMB training into interventional fellowships is important to prepare future operators. Given the low volume of EMBs, simulation platforms could play a pivotal role in enhancing procedural training and confidence.

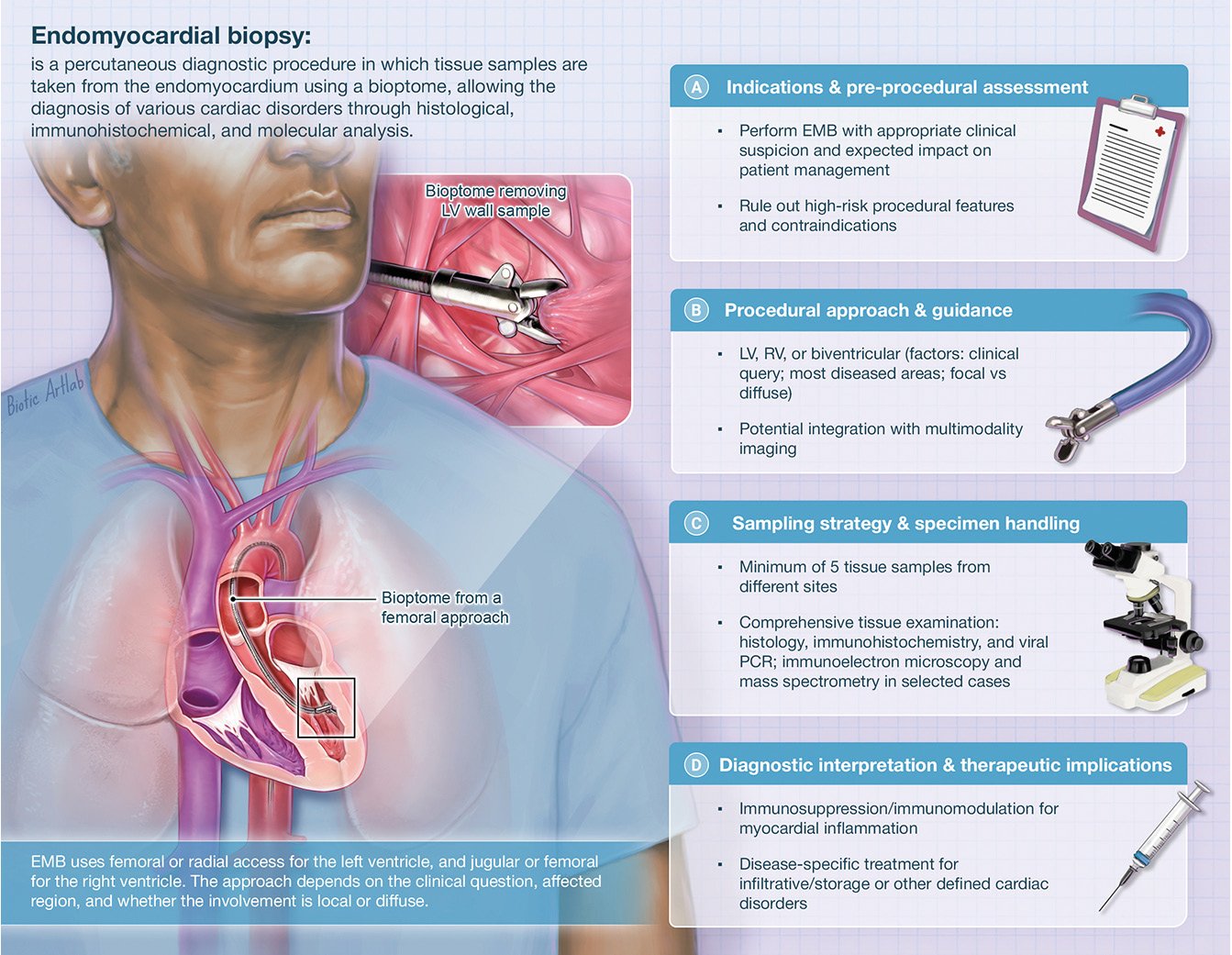

Finally, current EMB practices vary significantly between institutions; therefore, promoting standardised protocols for indications, tissue handling, and interpretation, along with disseminating both theoretical and practical training, is critical for ensuring safety, consistency, and reproducibility across centres. A multidisciplinary, Heart Team-based approach is vital for managing patients who require EMB. Such an approach should involve centres with specialised expertise in selecting suitable candidates, performing the procedure, and interpreting immunohistopathological and biomolecular findings. To optimise patient care, the establishment of a “hub-and-spoke” network should be strongly encouraged (Central illustration).

Central illustration. Key components for an EMB procedure. The figure illustrates the essential components for performing an endomyocardial biopsy. EMB: endomyocardial biopsy; LV: left ventricle; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; RV: right ventricle

Conclusions

For interventional cardiologists, EMB represents a unique opportunity to bridge invasive diagnostics with personalised care. By embracing technological advancements, integrating EMB with non-invasive modalities, the field can advance towards more precise and effective management of complex cardiac conditions such as myocarditis, CA, CS, and cardiomyopathies, which still have great margins of improvement in terms of outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript to declare.