Abstract

Non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) represents a unique clinical syndrome, comprising non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina. NSTEMI, as the more common and serious form of NSTE-ACS, is particularly noteworthy because of its diverse clinical presentation, electrocardiogram changes, and angiography findings, which may pose challenges in diagnosis and treatment and may subsequently influence prognosis. This review offers a comprehensive overview of current evidence-based approaches to NSTE-ACS management, focusing on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment strategies while highlighting emerging trends and ongoing challenges in optimising patient outcomes.

Non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS) encompass a spectrum of life-threatening cardiovascular conditions, including non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina (UA)1. Together, they account for a substantial proportion of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) cases globally and remain a major contributor to cardiovascular morbidity, mortality, and healthcare burden2. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) continue to be the primary cause of death in Europe, with ischaemic heart disease (IHD) being the most frequent contributor, accounting for 38% of all CVD-related deaths in females and 44% in males2. In 2019, an estimated 12.7 million new cases of CVD were reported across the 57 member countries of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), with 5.8 million of these cases attributed to IHD, the most common manifestation of CVD2.

NSTEMI, a critical subset of NSTE-ACS, is characterised by myocardial necrosis in the absence of persistent ST-segment elevation on electrocardiography, typically reflecting incomplete or transient coronary artery occlusion, although persistent complete occlusion can be present despite the absence of ST-segment elevation. While ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has a well-defined emergency diagnostic and therapeutic paradigm, the management of NSTEMI is inherently more complex. This complexity arises from its variable clinical manifestations, the need for precise risk stratification, and the interplay of multiple underlying mechanisms, including plaque rupture, erosion, and microvascular dysfunction3. Importantly, NSTEMI carries substantial prognostic risks, such as recurrent ischaemia, heart failure, and long-term cardiovascular events, underscoring the necessity for early diagnosis and tailored interventions4.

Significant progress has been made in the diagnosis and management of NSTE-ACS. Advances in sensitive cardiac biomarkers, particularly high-sensitivity troponins, have facilitated early detection, while risk stratification tools have improved the identification of high-risk patients requiring urgent intervention567. In parallel, therapeutic advancements, spanning antithrombotic therapies, platelet inhibitors, lipid-lowering agents, and early invasive strategies, including percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), have dramatically improved patient outcomes8. Nonetheless, the optimal selection, timing, and combination of these therapies remain subject to clinical judgment and are influenced by individual patient risk profiles, comorbidities, and haemodynamic stability. This article reviews current evidence-based approaches to NSTE-ACS management, focusing on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment strategies while highlighting emerging trends and ongoing challenges in optimising patient outcomes. Detailed discussion on cardiogenic shock, antithrombotic and secondary prevention therapies is beyond the scope of this review.

Early recognition, risk stratification, and initial management of NSTE-ACS

Electrocardiographic assessment

Management of NSTE-ACS starts from the point of first medical contact (FMC) when the first 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is performed, and a working diagnosis of NSTE-ACS is established. The working diagnosis of NSTE-ACS is based on symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischaemia and possible characteristic ECG changes such as ST-segment depression (horizontal or downsloping) and/or T-wave changes (especially biphasic T waves or prominent negative T waves)39. Additionally, transient ST-segment depression or transient ST-segment elevation may appear in NSTEMI, particularly in the setting of subtotal coronary occlusion or transient coronary vasospasm. Specific ECG patterns, such as Wellens’ syndrome, characterised by deeply inverted T waves or biphasic T waves in the anterior precordial leads (V2-V4), and de Winter T waves, which present as upsloping ST-segment depression with prominent T waves in the precordial leads, signify a critical proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) stenosis or occlusion, and thus are labelled as STEMI equivalents, emphasising the necessity of early (immediate) intervention. These distinctive ECG patterns underscore the importance of interpreting ECG changes in conjunction with clinical presentation and cardiac biomarkers, as they often represent significant myocardial ischaemia requiring urgent attention and immediate (early) invasive coronary angiography (ICA). However, the ECG in the setting of NSTE-ACS may be normal in more than one-third of patients, necessitating further evaluation and reliance on cardiac biomarkers and clinical assessment to confirm the diagnosis1310. Given the importance of ECG changes, their interpretation, and their prognostic value, they are one of the main features of risk stratification models. These models should guide prehospital treatment decisions, including the choice of target hospital (PCI centre vs non-PCI centre), thus influencing the decision between routine or selective ICA.

Role of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin

Besides ECG, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) is pivotal in the risk stratification of patients with NSTE-ACS. If the clinical presentation is consistent with myocardial ischaemia, then a dynamic elevation of cardiac troponin above the 99th percentile of healthy individuals indicates myocardial infarction (MI)9. Compared to conventional assays, hs-cTn enhances diagnostic sensitivity, particularly in patients presenting early after chest pain onset, enabling rapid “rule-in” or “rule-out” of MI, reducing unnecessary hospital admissions, and expediting appropriate care111. The higher sensitivity of hs-cTn allows shortened intervals between serial measurements, supporting the use of 0 h/1 h (preferred, best option) or 0 h/2 h algorithms (second-best option)1. These approaches achieve a negative predictive value (NPV) exceeding 99%, enabling early discharge and outpatient management for low-risk patients, while the positive predictive value (PPV) of 70-75% ensures most “rule-in” cases receive appropriate invasive coronary evaluation1213. Point-of-care (POC) hs-cTn assays have emerged as valuable tools in the prehospital setting1415. Due to their portability and rapid turnaround time, POC tests may be highly beneficial in prehospital settings, allowing early identification of low-risk suspected ACS patients without NSTEMI, significantly cutting healthcare costs and maintaining safety without compromising patient outcomes16. POC tests can also integrate with risk scores (e.g., a modified HEART score [history, ECG, age, risk factors, troponin] without troponin), enabling paramedics to stratify patients into low-risk or high-risk categories before hospital arrival16. In particular, in the randomised ARTICA trial17, it has been shown that prehospital identification of low-risk patients and rule-out of NSTE-ACS with POC troponin measurement is cost-effective, as expressed by a sustainable healthcare cost reduction and no difference in quality of life. Despite not being powered for clinical events, the safety of the prehospital rule-out of NSTE-ACS was comparable to the safety of standard transport to the emergency department (ED), with 1-year major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) remaining low for both strategies17. Additional trials are required with hs-cTn POC tests in the prehospital setting that are powered for hard clinical endpoints.

Risk prediction tools

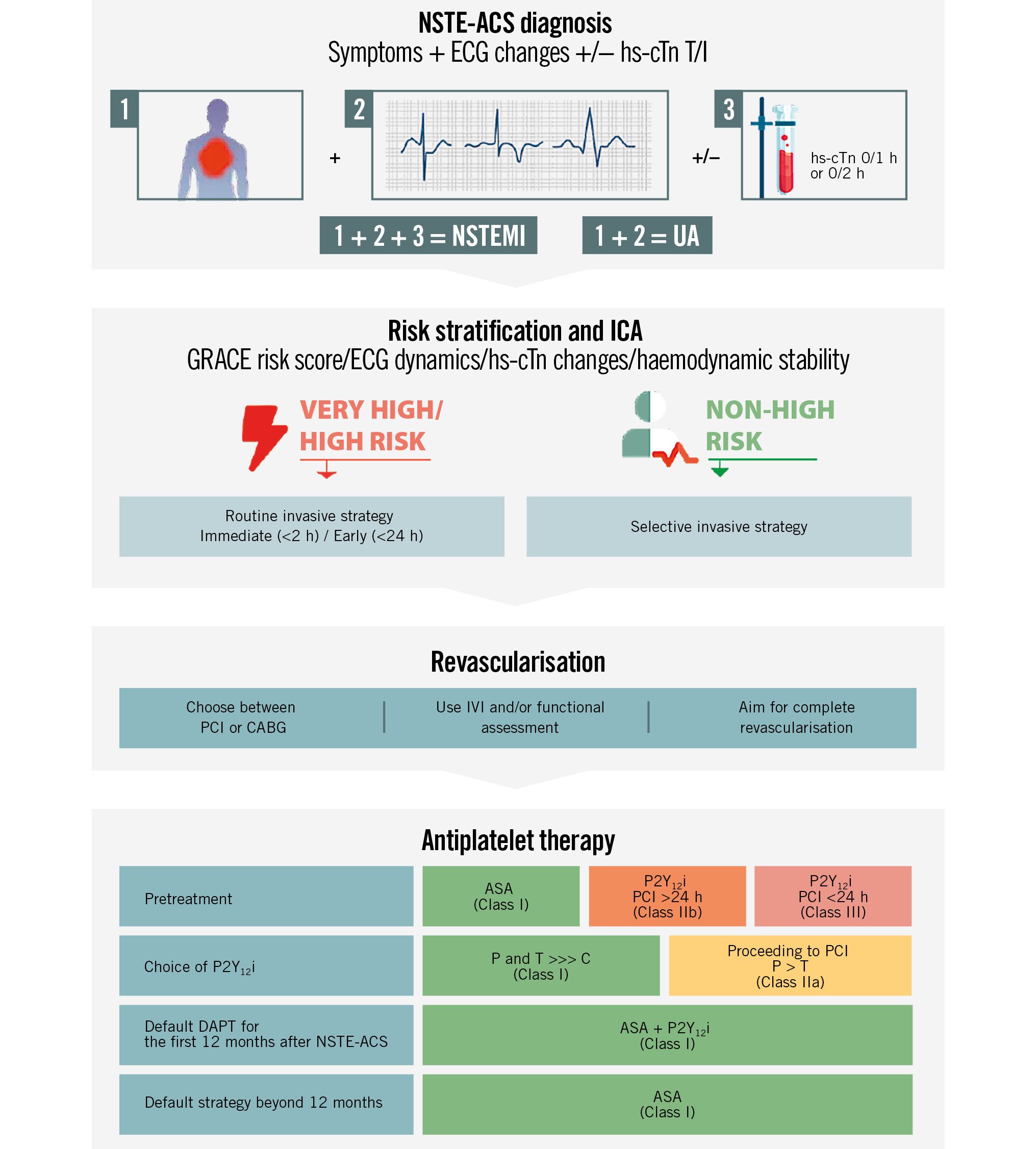

Several ACS risk prediction tools have been devised, with the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score considered the most robust in evaluating the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with ACS (Table 1)61819. Despite their usefulness in the decision-making process, risk scores are underutilised in clinical practice, especially since some evidence suggests a “risk-treatment” misalignment (the higher the risk, the lower the referral to angiography) in current clinical practice620. Moreover, the current risk models do not capture key prognostic variables, leading to an inaccurate estimation of patients’ baseline risk and subsequent mistreatment4. Therefore, efforts are needed to integrate clinical assessment, ECG, cardiac biomarkers, and risk scores into decision-making frameworks to identify patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes, who will benefit the most from revascularisation. The major aspects of the management of patients with NSTE-ACS are summarised in the Central illustration.

Table 1. GRACE and TIMI risk score variables.

| GRACE risk score (in-hospital mortality)18 | Points* | Explanation | TIMI risk score19 | Points§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0-100 | Increases with age: 0 points for ≤30 years, 100 points for ≥90 years | Age ≥65 years | 1 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 0-46 | Increases with HR: 0 points for ≤50 bpm, 46 points for ≥200 bpm | ≥3 CAD risk factors | 1 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 0-58 | Decreases with systolic BP: 58 points for ≤80 mmHg, 0 points for ≥200 mmHg | Known CAD (≥50% stenosis) | 1 |

| Serum creatinine level, mg/dL | 1-28 | Increases with serum creatinine level: 1 point for 0-0.39 mg/dL, 28 points for >4 mg/dL | ASA use in prior 7 days | 1 |

| Cardiac arrest at admission | 39 | No: 0 points, Yes: 39 points | ≥2 anginal events in prior 24 h | 1 |

| ST-segment deviation on ECG | 28 | No: 0 points, Yes: 28 points | ST-segment deviation on ECG (≥0.5 mm) | 1 |

| Abnormal cardiac enzymes | 14 | No: 0 points, Yes: 14 points | Elevated cardiac biomarkers | 1 |

| Killip class | 0-59 | I: 0 points, II: 20 points, III: 39 points, IV: 59 points | ||

| Total points | 0-372 | 0-7 | ||

| *Score (points) − probability of in-hospital mortality (%): ≤108 − low risk (<1%); 109-140 − intermediate risk (1-3%); >140 − high risk (>3%). §Score (points) − probability of developing at least 1 component of the primary endpoint (all-cause mortality, new or recurrent MI, or severe recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation) up to 14 days: 0-1 − 4.7%; 2 − 8.3%; 3 − 13.2%; 4 − 19.9%; 5 − 26.2%; and 6-7 − 40.9%. ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; BP: blood pressure; CAD: coronary artery disease; ECG: electrocardiogram; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HR: heart rate; MI: myocardial infarction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction | ||||

Central illustration. Management of NSTE-ACS patients. ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; C: clopidogrel; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; ECG: electrocardiogram; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; hs-cTn: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; IVI: intravascular imaging; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; P: prasugrel; P2Y12i: P2Y12 inhibitor; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; T: ticagrelor; UA: unstable angina

Routine invasive versus conservative (selective invasive) strategy

The choice between an invasive and conservative strategy for managing NSTE-ACS is guided by the patient’s clinical risk profile and the anticipated benefit of early revascularisation. An invasive strategy involves routine coronary angiography, followed by revascularisation (PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) if indicated, while a conservative (selective invasive) strategy reserves angiography for patients with refractory symptoms or evidence of ischaemia on non-invasive testing13. Several randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and their meta-analyses have shaped the current guidelines, emphasising the role of risk stratification in determining the optimal approach2122232425262728. Landmark trials, such as FRISC-II2122, RITA 32329, and TACTICS-TIMI 1824, provide evidence for early invasive management in high-risk patients, showing that a routine invasive strategy offers benefits in reducing the composite endpoint of death or MI.

Long-term outcomes of routine invasive versus selective invasive strategies

The RITA 3 and FRISC-II trials have also provided valuable insights into the long-term outcomes of routine invasive versus selective invasive strategies in patients with NSTE-ACS. The 5-year results of the RITA 3 trial showed that a routine invasive strategy significantly reduced the composite endpoint of death or non-fatal MI compared to a selective invasive approach (odds ratio [OR] 0.78, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61-0.99; p=0.044). This benefit was even greater in high-risk patients, with a more pronounced reduction in death or MI (OR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.25-0.76)29. Similarly, 5-year follow-up of the FRISC-II trial demonstrated that a routine invasive strategy resulted in a lower incidence of the composite endpoint of death or MI compared to a non-invasive strategy (relative risk [RR] 0.81, 95% CI: 0.69-0.95; p=0.009), primarily due to a decrease in non-fatal MIs (12.9% vs 17.7%; p=0.002)22. The FRISC-II trial demonstrated a sustained benefit of the invasive strategy, persisting up to 15 years (75.9% vs 84.2%; p=0.002). The difference was mainly driven by the postponement of new MI, whereas the early difference in mortality was not sustained over time30. The advantage of reduced mortality from a routine invasive strategy seen at 5 years in the RITA 3 trial diminished over time, with no significant differences in all-cause mortality or cardiac mortality at the 10-year follow-up31. However, the risk of death within 10 years varied markedly from 14.4% in the low-risk group to 56.2% in the high-risk group, regardless of the assigned treatment strategy.

Meta-analysis of routine invasive versus selective invasive strategies

A meta-analysis by Elgendy et al28, which included 8 RCTs with 6,657 patients comparing a routine invasive with a selective invasive strategy, revealed no significant difference in long-term mortality (~10 years) between the two strategies. The main weight of this meta-analysis was driven by long-term follow-up of three of the above-mentioned trials (FRISC-II, ICTUS, and RITA 3)2225293031. The lack of survival advantage at 10-year follow-up should be interpreted as the consequence of a previous reduction in ischaemic events, particularly MI and revascularisation, with the routine invasive approach. An important consideration is that these trials were conducted in an earlier era − prior to the widespread adoption of routine radial access, second-generation drug-eluting stents, contemporary biomarker assays for identifying high-risk patients, and modern adjunctive pharmacological therapy, including more potent antiplatelet agents.

Timing of invasive strategy

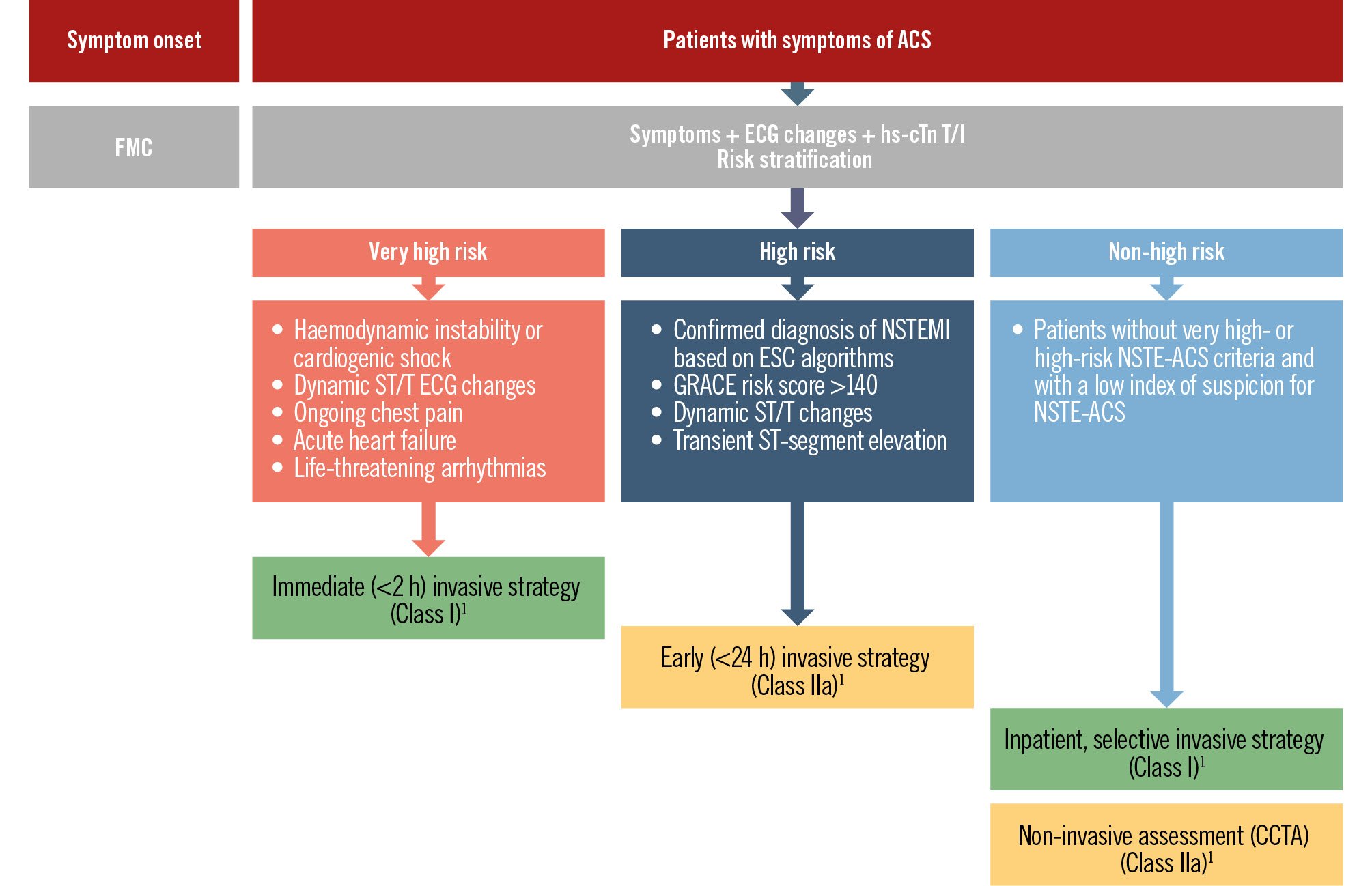

Patients with a very high-risk profile – such as those with haemodynamic instability or cardiogenic shock, recurrent dynamic ECG changes (particularly intermittent ST-segment elevation), ongoing chest pain refractory to medical treatment, or life-threatening arrhythmias – warrant an immediate invasive strategy within two hours of admission (Class I, Level of Evidence [LoE] C) (Figure 1)1310. However, there is an ongoing debate as to whether high-risk NSTE-ACS patients should systematically undergo an early ICA (within 24 hours of admission)32333435363738394041424344454647484950515253.

Figure 1. Risk stratification and timing of invasive coronary angiography in patients presenting with NSTE-ACS. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; ECG: electrocardiogram; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; FMC: first medical contact; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; hs-cTn T/I: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T/I; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Clinical practice guidelines

Both the 2023 ESC1 and 2025 ACC/AHA54 guidelines recommend early coronary angiography in patients with NSTE-ACS who are at high risk, but they differ in specific criteria and the level of rigidity regarding risk stratification tools. The ESC provides a structured approach, recommending an early invasive strategy (within 24 hours) for patients with any of the following high-risk criteria such as GRACE risk score >140, dynamic ST/T changes, transient ST-segment elevation, or elevated troponin levels (Class IIa, LoE A)1. In contrast, the ACC/AHA adopts a more flexible, patient-centred model. It recommends angiography during hospitalisation for intermediate- or high-risk patients, with an early invasive strategy within 24 hours being a reasonable option in high-risk cases (Class IIa, LoE B-R)54. Notably, the ESC places greater emphasis on structured risk stratification, while the ACC/AHA supports clinician-guided risk assessment, informed, but not dictated, by tools like GRACE and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) (Table 2).

Table 2. ESC and ACC/AHA guidelines: risk stratification features/aspects.

| ESC 2023 guidelines1 | ACC/AHA 2025 guidelines54 | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary risk assessment tool | GRACE score: the cornerstone for risk stratification, based on eight variables; provides continuous and validated risk spectrum for in-hospital and long-term mortality | GRACE score, TIMI score and clinical profile. TIMI score is a simple, categorical tool based on seven clinical variables; estimates risk for all-cause mortality, new or recurrent MI, or severe recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation at 14 days |

| Integration of biomarkers | High-sensitivity troponins integrated with GRACE score for enhanced risk stratification | Troponin levels guide decision-making but have less emphasis on scoring |

| Approach to risk stratification/decision framework | Structured, algorithmic pathways incorporating GRACE score and biomarker-based refinements | Flexible, emphasising clinical judgment and shared decision-making alongside GRACE and TIMI scoring |

| Timing of invasive coronary angiography | Immediate (<2 h) Early (<24 h) Selective invasive | Immediate (<2 h) Early (<24 h) Delayed (<72 h) Ischaemia-guided (before hospital discharge) |

| Very high risk definition | Refractory angina Signs and symptoms of HF or worsening MR Haemodynamic instability Recurrent angina or ischaemia at rest or with low-level activities despite intensive medical therapy Sustained VT or VF | Cardiogenic shock Signs or symptoms of HF including new/worsening MR or acute pulmonary oedema Refractory angina Haemodynamic or electrical instability (e.g., sustained VT or VF) |

| ICA within 2 h (Class I) | ICA within 2 h (Class I) | |

| High risk definition | GRACE risk score >140 Dynamic ST/T changes Transient ST-segment elevation Confirmed diagnosis of NSTEMI based on current recommended ESC hs-cTn algorithms | GRACE risk score >140 Steeply rising Tn values on serial testing despite optimised medical therapy Ongoing dynamic ST-segment changes |

| ICA within 24 h (Class IIa) | ICA within 24 h (Class IIa) | |

| Non-high risk definition | Non-high risk | Intermediate risk |

Patients without very high- or high-risk NSTE-ACS criteria and with a low index of suspicion for NSTE-ACS | GRACE risk score 109-140 Absence of ongoing ischaemic symptoms Stable or downtrending Tn values | |

| ICA before hospital discharge <72 h (Class IIa) | ||

| Selective invasive strategy (Class I) | Low risk | |

| GRACE risk score <109 | ||

| TIMI risk score <2 | ||

| Absence of ongoing ischaemic symptoms | ||

| Tn <99th percentile (i.e., unstable angina) | ||

| No dynamic ST-segment changes | ||

| Routine or selective invasive strategy before hospital discharge (Class IIa) | ||

| Primary role of CCTA | CCTA is recommended for the rule-out of ACS in low-risk patients where high-sensitivity troponins and ECG are inconclusive (Class IIa) | CCTA is emphasised as a diagnostic tool in low-risk patients with suspected ACS and non-diagnostic initial tests (Class I) |

| Flexibility versus structure of risk stratification | Highly structured, systematic integration of GRACE score and clinical tools into clinical pathways | More flexible, relying on clinical judgment |

| Healthcare system context | European healthcare integration emphasises systematic scoring | US-centric focus on cost-effectiveness and individual risk assessment |

| ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; ECG: electrocardiogram; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; GRACE: Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; HF: heart failure; hs-cTn: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; MI: myocardial infarction; MR: mitral regurgitation; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; Tn: troponin; VF: ventricular fibrillation; VT: ventricular tachycardia | ||

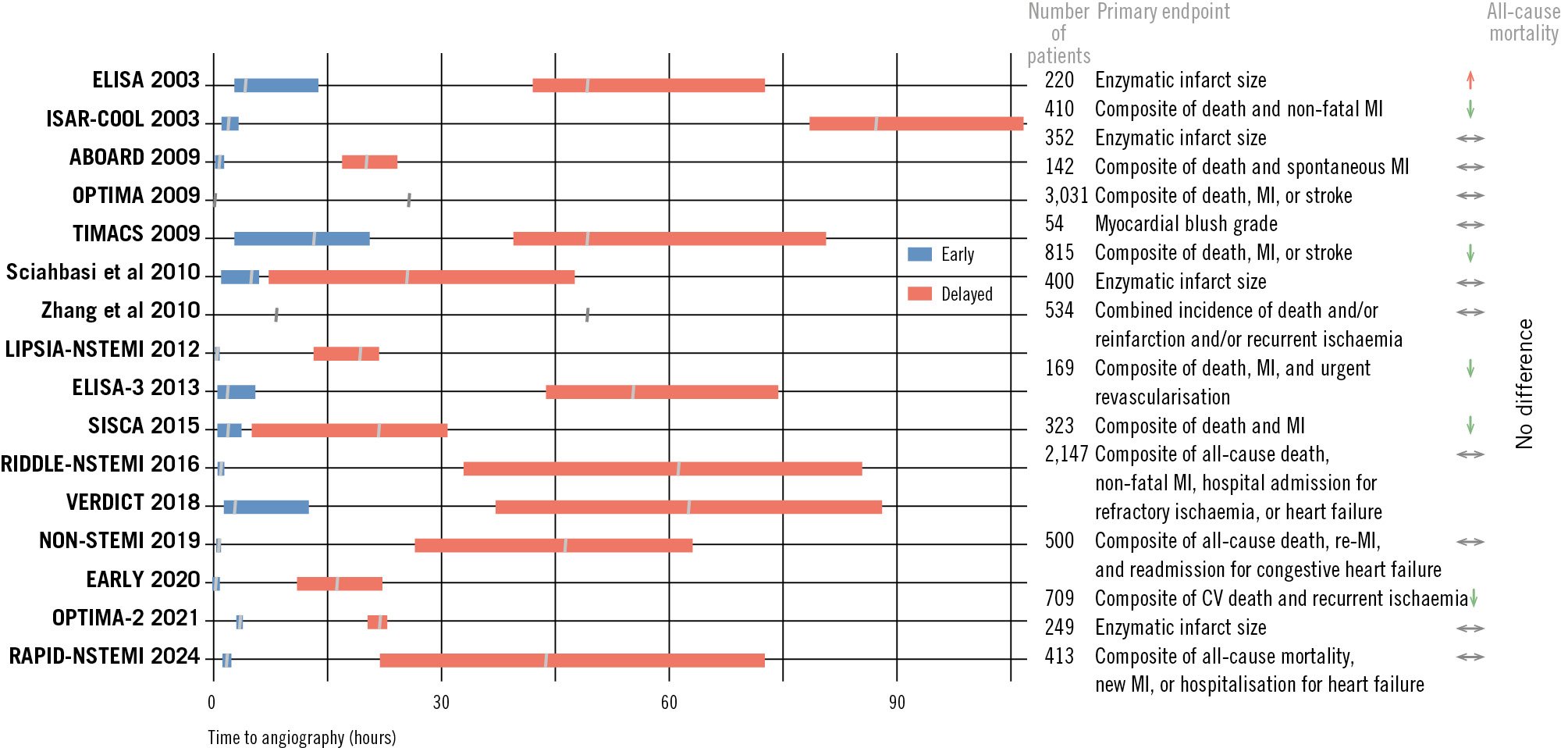

RCTs and meta-analyses on early versus delayed invasive strategies

Several RCTs (Table 3, Figure 2) and meta-analyses323334353637383940414243444546474849505152 have concluded that an early (<24 h) invasive strategy does not reduce the risk of all-cause mortality, but it does reduce refractory angina in unselected NSTE-ACS patients. However, in high-risk patients, an early invasive strategy is highly beneficial in mortality reduction3546515255. An individual patient data meta-analysis by Jobs et al51, consisting of eight RCTs (n=5,324 NSTE-ACS patients) with a median follow-up of 180 days, concluded that there was no significant mortality reduction in the early invasive group compared with the delayed invasive group (hazard ratio [HR] 0.81, 95% CI: 0.64-1.03; p=0.0879). However, lower mortality with an early invasive strategy was found in patients with elevated cardiac biomarkers at baseline, in those with diabetes, in patients with a GRACE risk score >140, and in those aged ≥75 years51.

A study-level meta-analysis by Kite et al52, which did not allow for high-risk subgroup analyses, included 17 RCTs with outcome data from 10,209 NSTE-ACS patients. No significant differences in the risk of all-cause mortality, MI, hospital admission for heart failure (HF), repeat revascularisation, major bleeding, or stroke were observed. However, recurrent ischaemia (RR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.40-0.81) was reduced with an early invasive strategy52.

In both meta-analyses, two prominent, large RCTs − TIMACS35 and VERDICT46, conducted 10 years apart − significantly influenced the findings. The TIMACS35 trial, which included 3,031 patients, showed no benefit of an early invasive strategy (<24 h, with a median time of 14 h) compared to a delayed invasive strategy (>36 h, with a median time of 50 h) in terms of the primary endpoint – death, MI or stroke at 6 months (9.6% vs 11.3%; HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.68-1.06; p=0.15). However, it demonstrated an RR reduction of 28% in the secondary outcomes of death, MI, or refractory ischaemia in the early invasive group, as compared with the delayed invasive group (9.5% vs 12.9%; HR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.58-0.89; p=0.003). In a prespecified subgroup analysis, patients with a GRACE risk score >140 benefitted from an early invasive strategy, which resulted in a reduction of both primary (HR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.48-0.89; p=0.006) and secondary endpoints (HR 0.62, 95% CI: 0.45-0.83; p=0.002)35.

In the VERDICT trial, which included 2,147 patients, an early invasive strategy (at a median of 4.7 h after diagnosis) was not superior to a delayed strategy (a median of 61.6 h) among unselected (all-comer) NSTE-ACS patients with regard to composite clinical endpoints (all-cause death, non-fatal recurrent MI, hospital admission for refractory myocardial ischaemia, or hospital admission for HF) at a median follow-up of 4.3 years. However, high-risk patients (GRACE risk score >140) benefitted the most, with a 19% RR reduction (HR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.67-1.00)46.

As a result of the findings of the above-mentioned RCTs and meta-analyses, the most prominent high-risk feature that should guide the timing of ICA and subsequent revascularisation was a GRACE risk score >140. However, due to a lack of studies assessing the value of a GRACE risk score >140 to guide the timing of ICA and revascularisation and inconsistent data on long-term outcomes, the current ESC guidelines state that the GRACE risk score should be considered (Class IIa) for estimating prognosis3.

Table 3. RCTs comparing early versus delayed ICA in NSTE-ACS patients.

| RCT and author | Year | Early intervention | Delayed intervention | Early group timing, hours | Delayed group timing, hours | Treatment – early intervention | Treatment – delayed intervention | Primary endpoint | All-cause mortality | Longest clinical outcome follow-up duration available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA van ’t Hof et al32 | 2003 | 109 | 111 | 6 (4-14) | 50 (42-73) | Medicala: 27 (25) PCI: 66 (61) CABG: 15 (14) | Medical: 26 (23) PCI: 64 (58) CABG: 21 (19) | Enzymatic infarct size (¯ in delayed group) | No difference | 30 days |

| ISAR-COOL Neumann et al33 | 2003 | 203 | 207 | 2.4 (1.0-4.3) | 87.4 (78.2-106.7) | Medical: 44 (22) PCI: 143 (70) CABG: 16 (8) | Medical: 58 (28) PCI: 133 (64) CABG: 16 (8) | Composite of death and non-fatal MI (¯ in early group) | No difference | 30 days |

| ABOARD Montalescot et al34 | 2009 | 175 | 177 | 1.10 (0.51-2.03) | 20.48 (17.30-24.36) | Medical: 42 (24) PCI: 117 (67) CABG: 16 (9) | Medical: 55 (31) PCI: 105 (59) CABG: 17 (10) | Enzymatic infarct size (no difference) | No difference | 30 days |

| TIMACS Mehta et al35 | 2009 | 1,593 | 1,438 | 14 (3-21) | 50 (41-81) | Medical: 384 (24) PCI: 954 (60) CABG: 225 (16) | Medical: 423 (29) PCI: 796 (55) CABG: 219 (15) | Composite of death, MI, or stroke (no difference) | No difference | 6 months |

| Sciahbasi et al36 | 2010 | 27 | 27 | 5 (1-6)b | 24 (8-48)b | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 27 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 27 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Myocardial blush grade (no difference) | Not reported | 1 year |

| Zhang et al37 | 2010 | 446 | 369 | 9.3c | 49.9c | Medical: 91 (20) PCI: 314 (70) CABG: 41 (9) | Medical: 20 (22) PCI: 252 (68) CABG: 37 (10) | Composite of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (¯ in early group) | No difference | 6 months |

| LIPSIA-NSTEMI Thiele et al38 | 2012 | 200 | 200 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 18.3 (14.0-21.2) | Medical: 33 (17) PCI: 151 (76) CABG: 16 (8) | Medical: 34 (17) PCI: 141 (71) CABG: 25 (13) | Enzymatic infarct size (no difference) | No difference | 6 months |

| ELISA-3 Badings et al39 | 2013 | 269 | 265 | 2.6 (1.2-6.2) | 54.9 (44.2-74.5) | Medical: 27 (10) PCI: 180 (67) CABG: 62 (23) | Medical: 33 (12) PCI: 164 (62) CABG: 68 (26) | Combined incidence of death and/or reinfarction and/or recurrent ischaemia (no difference) | No difference | 2 years |

| Tekin et al40 | 2013 | 69 | 62 | <24d | 24-72d | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 69 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 62 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Composite of all-cause death, recurrent MI, and rehospitalisation for cardiac event (¯ in early group) | No difference | 3 months |

| Liu et al41 | 2015 | 22 | 20 | <12d | 12-24d | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 22 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 20 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Not specified | ¯ in early group | 6 months |

| SISCA Reuter et al42 | 2015 | 83 | 86 | 2.8 (1.4-4.7) | 20.9 (6.1-31.2) | Medical: 25 (32) PCI: 45 (58) CABG: 8 (10) | Medical: 23 (30) PCI: 45 (59) CABG: 8 (11) | Composite of death, MI, and urgent revascularisation (¯ in early group) | No difference | 30 days |

| OPTIMA Oosterwerff et al43 | 2016 | 73 | 69 | 0.5c,e | 25c,e | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 73 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Medical: 0 (0) PCI: 69 (100) CABG: 0 (0) | Composite of death and spontaneous MI (no difference) | No difference | 5 years |

| RIDDLE-NSTEMI Milosevic et al44 Milasinovic et al45 | 2016/ 2018 | 162 | 161 | 1.40 (1.00-2.24) | 61.0 (35.8-85.0) | Medical: 15 (9) PCI: 127 (78) CABG: 20 (12) | Medical: 18 (11) PCI: 104 (65) CABG: 38 (24) | Composite of death and MI (¯ in early group)f | No difference | 3 years |

| VERDICT Kofoed et al46 | 2018 | 1,075 | 1,072 | 4.7 (3.0-12.2) | 61.6 (39.4-87.8) | Medical: 445 (42) PCI: 498 (46) CABG: 132 (12) | Medical: 498 (47) PCI: 442 (41) CABG: 132 (12) | Composite of all-cause death, non-fatal recurrent MI, hospital admission for refractory ischaemia, or hospital admission for heart failure (no difference) | No difference | Median follow-up of 4.3 years |

| NONSTEMI Rasmussen et al47 | 2019 | 247 | 253 | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) | 47.8 (25.8-67.1) | Medical: 14 (8) PCI: 124 (73) CABG: 21 (12) Hybrid: 10 (6) | Medical: 13 (7) PCI: 122 (68) CABG: 36 (20) Hybrid: 8 (5) | Composite of all-cause death, reinfarction, and readmission with congestive heart failure (no difference) | No difference | 1 year |

| EARLY Lemesle et al48 | 2020 | 346 | 363 | 0 (0-1) | 18 (12-23) | Medical: 82 (25) PCI: 230 (72) CABG: 9 (3) | Medical: 64 (19) PCI: 262 (78) CABG: 10 (3) | Composite of CV death and recurrent ischaemia (¯ in early group) | No difference | 30 days |

| OPTIMA-2 Fagel et al49 | 2021 | 125 | 124 | 2.94 (2.5-3.4)b | 22.8 (20.7-24.2)b | Medical: 41 (33) PCI: 59 (47) CABG: 24 (19) | Medical: 33 (26) PCI: 75 (61) CABG: 15 (12) | Enzymatic infarct sizeg | No difference | 1 year |

| RAPID-NSTEMI Kite et al50 | 2024 | 204 | 209 | 1.5 (9.0-2.0) | 44.0 (22.9-72.6) | Medical: 62 (30) PCI: 122 (60) CABG: 20 (10) | Medical: 56 (27) PCI: 132 (63) CABG: 21 (10) | Composite of all-cause mortality, new MI or hospitalisation for heart failure (no difference)h | No difference | 1 year |

| Data are presented as n, n (%), or median (IQR). aMedical therapy alone; btiming of angiography was reported as the time interval from admission to angiography; cIQRs were not reported; dmedian timing of coronary angiography was not reported; etiming of coronary angiography was the time interval from randomisation (performed at initial angiography when PCI was deemed to be the most appropriate revascularisation strategy) to receipt of PCI; fthe benefit observed with early intervention was primarily attributed to a higher risk of early reinfarction in the delayed strategy, while the rates of new MI beyond 30 days were similar; gthe observed median difference in the primary endpoint was approximately half as large as the anticipated difference, and the trial was prematurely terminated for futility after 71% of the planned enrolment had been randomised; hthe primary outcome rate was low, and the trial was underpowered to detect such a difference. CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CV: cardiovascular; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; IQR: interquartile range; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; RCT: randomised controlled trial | ||||||||||

Figure 2. RCTs comparing early versus delayed invasive coronary angiography in NSTE-ACS. For trial references, see Table 3. CV: cardiovascular; MI: myocardial infarction; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; RCT: randomised controlled trial

Transient ST-segment elevation

Patients with “transient ST-segment elevation”, which is considered to be one of the high-risk features, in the small RCT by Lemkes et al55 did not have any benefit of an early invasive (STEMI-like) strategy in comparison to a delayed (NSTEMI-like) revascularisation in terms of MACE (defined as death, reinfarction, or target vessel revascularisation) at 30 days (2.9% vs 2.8%; p=1.00). Furthermore, infarct size in transient ST-segment elevation patients was small and was not influenced by an immediate or delayed invasive strategy55.

Role of total ischaemic time

In all the aforementioned trials and meta-analyses, the timeframe was defined according to the “door-to-catheter” time, thus not including the time from symptom onset or total ischaemic time, which is known to impact prognosis in STEMI patients. In KAMIR-NIH, a prospective registry of 5,856 NSTEMI patients, the association between symptom-to-catheterisation (StC) time and clinical outcomes was evaluated56. Patients with an StC delay <48 h had lower 3-year all-cause mortality as the primary outcome, compared to those with a longer StC time interval (7.3% vs 13.4%; p<0.001). Furthermore, they had lower rates of cardiac mortality and hospitalisation for HF (4.2% vs 8.0%; p<0.001, and 2.9% vs 6.2%; p<0.001, respectively)56. The lower risk for all-cause mortality in the group with an StC time <48 h was consistent across all subgroups. Cha et al57 reported that delayed hospitalisation (>24 h after symptom onset) in NSTEMI patients, observed in 27.9% of cases during a 3-year follow-up, was associated with a 1.6-fold increase in mortality compared to those who arrived within 24 h.

Over the past two decades, 6-month mortality following NSTEMI has significantly decreased (from 17.2% in 1995 to 6.3% in 2015), largely attributed to the increased use of PCI within 72 h from admission (9% in 1995 to 60% in 2015)8. However, in the trials referenced (Table 3), up to 40% of patients were managed with medical therapy alone, without undergoing revascularisation (PCI or CABG). This underscores that NSTEMI patients constitute a distinct subgroup of ACS cases, characterised by variability in clinical presentation and angiographic findings, as well as alternative diagnoses including Type 2 MI, among others, which make their management particularly challenging46. These findings may suggest that total ischaemic time, rather than door-to-catheter time, plays a crucial role in high-risk NSTEMI patients and should be considered as an important factor in reducing all-cause mortality.

Role of computed tomography angiography in low-risk patients

In patients who do not meet any of the very high-risk or high-risk criteria (non-very high/high-risk patients), who are generally patients with clinical suspicion of NSTE-ACS but with inconclusive hs-cTn or patients with elevated hs-cTn but without ECG changes, management should be tailored to each patient individually, with the utility of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) or non-invasive test being advocated if needed (Class IIa, LoE A) (Figure 1)1.

However, contradictory results regarding the usefulness of CCTA have been recorded. A meta-analysis of 4 RCTs reported that CCTA was associated with an increase in the use of ICA (there was 1 additional ICA for every 48 patients and 1 additional revascularisation for every 50 patients evaluated with CCTA)58. In a recent RCT of unclear NSTEMI diagnosis, upfront imaging with CCTA reduced the need for ICA59. Similar results were observed in a subanalysis of the VERDICT trial, where upfront CCTA in NSTE-ACS patients had high diagnostic performance to rule out or rule in significant coronary artery disease (CAD; defined as stenosis ≥50%), with a negative predictive value of 90.9% and a positive predictive value of 87.9%60.

The RAPID-CTCA trial61 evaluated the impact of early CCTA in identifying ACS patients who would benefit from more rapid and appropriate therapeutic interventions, thus improving clinical outcomes. The trial included 1,748 intermediate-risk ACS patients (mean GRACE score of 115), who were randomised to receive early CCTA (median time of 4.2 hours) in addition to standard care or to standard care alone. In total, 1,004 patients (57%) had raised levels of cardiac troponin. Notably, elevated troponin was observed in 39% of patients with normal coronary arteries and 49% of patients with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. The trial concluded that an early CCTA did not alter 1-year clinical outcomes. The composite endpoint of all-cause death or subsequent non-fatal Type 1 or 4b MI occurred in 5.8% of the CCTA group and 6.1% of the standard-care group, showing no significant difference (adjusted HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.62-1.35; p=0.65)61. The study did highlight a 19% RR reduction in the hazard for ICA, likely due to the ability of CCTA to rule out obstructive coronary artery disease, thus avoiding unnecessary invasive procedures in patients with elevated troponin levels unrelated to myocardial infarction or obstructive disease. However, this benefit was offset by a modest increase in the length of hospital stay61. These findings do not support the routine use of early CCTA in intermediate-risk patients with suspected ACS. In addition, a variety of factors may influence the decision to pursue ICA after CCTA, including the quality of the CCTA images, anatomical details regarding the location and severity of stenosis, the presence of specific high-risk features such as the “napkin-ring” sign, overall clinical judgment, and finally, the experience and expertise of the readers of the CCTA images.

Role of cardiac magnetic resonance

The diagnostic utility of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) before ICA in suspected NSTEMI has been assessed in several randomised and observational trials59626364. Smulders et al59 randomised patients with suspected NSTEMI to either CMR (n=60), CCTA (n=70) or ICA (n=68) and found that a CMR-first strategy obviated the need for ICA in 13% of patients, with similar clinical outcomes in the three cohorts at 1-year follow-up.

Besides the ability to reduce the need for ICA, CMR has demonstrated accuracy in detecting obstructive CAD and identifying the infarct-related artery (IRA) in suspected NSTEMI, thereby guiding targeted revascularisation strategies that improve outcomes6364. In the prospective study by Heitner et al63, the IRA was not identifiable by coronary angiography in 37% of patients. In these patients, the IRA or a new non-coronary artery disease diagnosis was identified by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE)-CMR in 60% and 19% of patients, respectively. Even in patients with an IRA determined by coronary angiography, a different IRA was identified by LGE-CMR in 14% of cases. Overall, LGE-CMR led to a new IRA diagnosis in 31% and a diagnosis of non-ischaemic pathogenesis in 15%.

In the study by Shanmuganathan et al62, early CMR (a median of 33 h after admission and 4 h pre-ICA) confirmed an MI diagnosis in 67% of patients (52% with subendocardial infarction, and 15% with transmural infarction, likely late-presenting STEMI), whereas alternative diagnoses were a non-ischaemic pathology (myocarditis, Takotsubo syndrome, and other forms of cardiomyopathies) in 18% and normal findings in 11% of patients. Accordingly, a CMR-first strategy has the potential to change diagnosis and/or management in at least 50% of patients presenting with suspected NSTEMI.

In patients with NSTE-ACS and multivessel disease (MVD), an identifiable culprit lesion may be absent in up to 30% of patients, while >10% of patients may have multiple culprit lesions on angiography65. In such circumstances, CMR may be a valuable option to identify the IRA in multivessel NSTE-ACS, guiding clinical decision-making and revascularisation.

Angiographic findings and the role of intravascular imaging

Angiographic findings in NSTE-ACS may be non-obstructive (<50%) or obstructive (≥50%) CAD (Figure 3, Figure 4). An early pioneering acute MI (AMI) coronary angiography study by DeWood et al66 demonstrated that, in contrast to patients presenting with STEMI (where almost 90% had an occluded coronary artery), in AMI patients who did not present with ST-segment elevation, total coronary occlusion was less frequently observed, with 26% having an occluded coronary artery when angiography was performed within 24 h of symptom onset. It is interesting to note that 10% had no significant CAD on coronary angiography66.

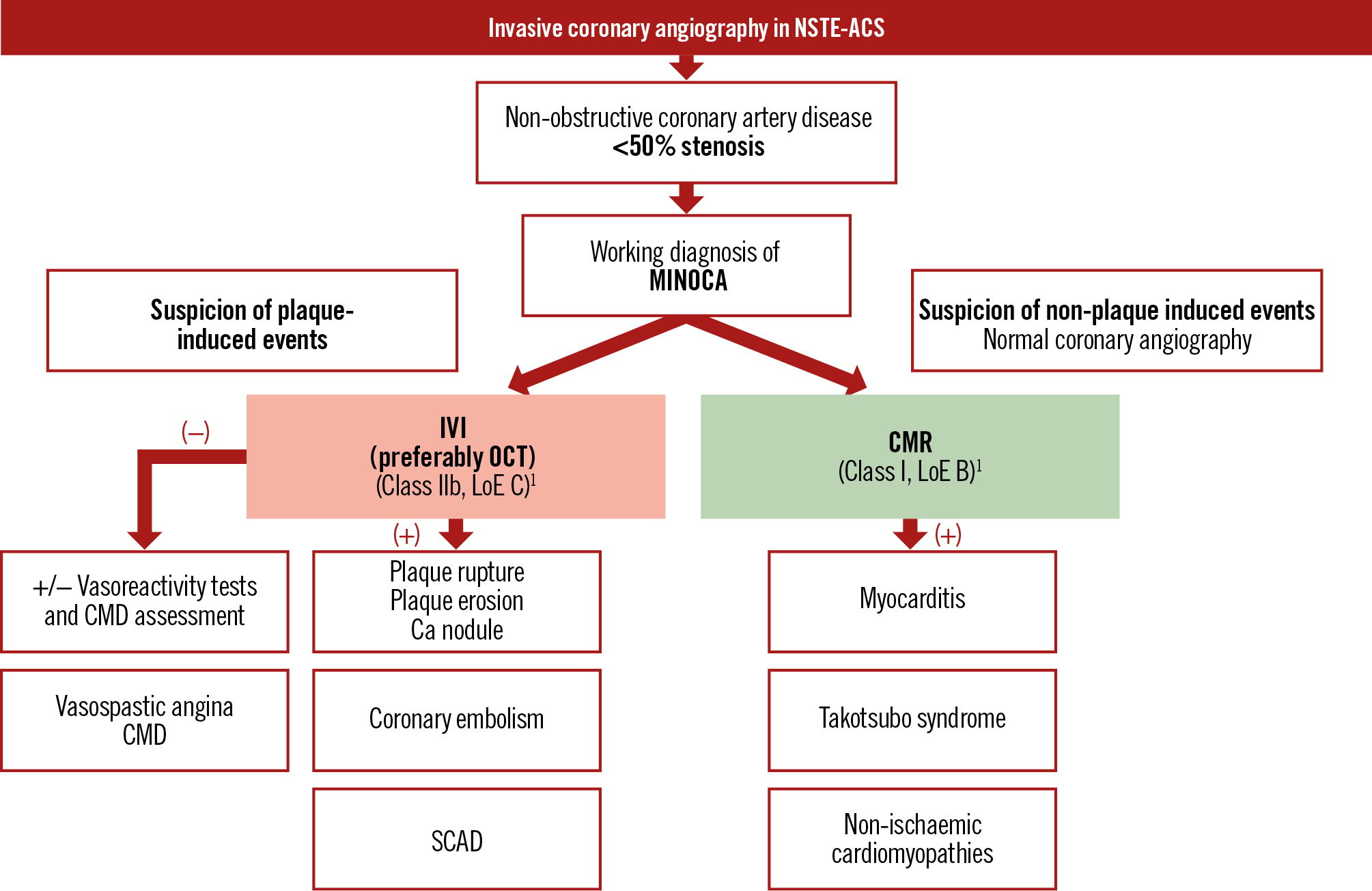

Figure 3. Proposed algorithm for patients without obstructive coronary artery disease on invasive coronary angiography. Ca: calcium; CMD: coronary microvascular dysfunction; CMR: cardiac magnetic resonance; IVI: intravascular imaging; LoE: Level of Evidence; MINOCA: myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OCT: optical coherence tomography; SCAD: spontaneous coronary artery dissection

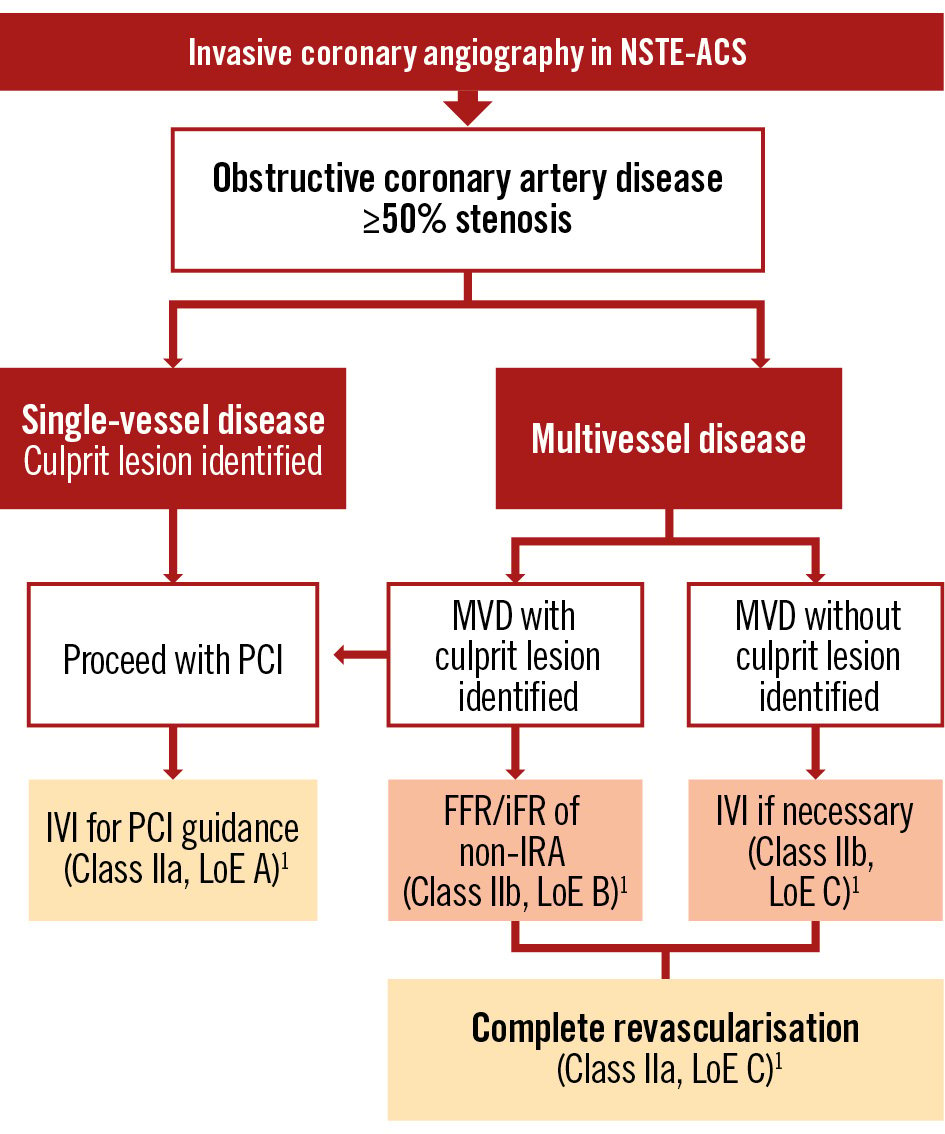

Figure 4. Proposed algorithm for patients with obstructive coronary artery disease on invasive coronary angiography. FFR: fractional flow reserve; iFR: instantaneous wave-free ratio; IRA: infarct-related artery; IVI: intravascular imaging; LoE: Level of Evidence; MVD: multivessel disease; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries

Although obstructive CAD (≥50% stenosis) is seen in most patients presenting with NSTEMI, there is increasing awareness that a proportion of all MI patients do not have evidence of obstructive CAD on angiography. Due to the ambiguity of the underlying cause of this particular finding, clinical researchers created the term “myocardial infarction/injury with non-obstructive coronary arteries” (MINOCA)6768. The prevalence of MINOCA among patients with NSTEMI varies across studies, ranging from ~5-14%, and disproportionately affects females96869. The conventional cutoff of 50% diameter stenosis for defining obstructive CAD is based on studies that determined what degree of stenosis is flow-limiting and may cause ischaemia under stress68.

MINOCA was previously considered to be “non-atherosclerotic AMI”, mainly due to the infrequent use of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT) in routine clinical practice. Currently, MINOCA is defined by the absence of obstructive stenosis on ICA, though it may still involve atherosclerosis (<50% stenosis). Furthermore, coronary atherosclerosis may also be an “innocent bystander” in non-ischaemic causes of elevated troponin (myocarditis and Takotsubo syndrome).

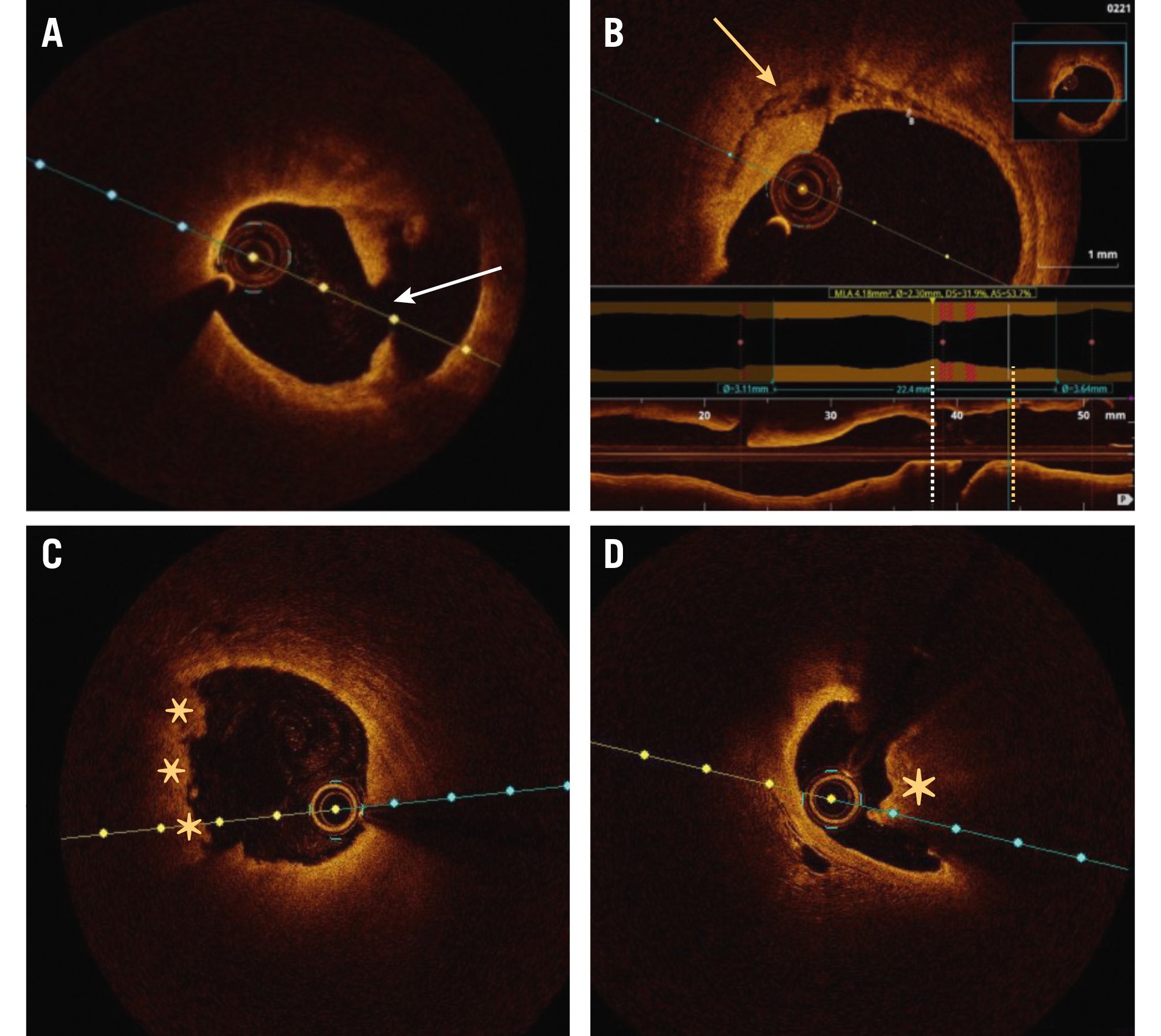

Plaque disruption as a mechanism of MI with/without obstructive coronary artery disease and the importance of intravascular imaging

The most common underlying culprit lesion in ACS patients is a plaque disruption, primarily due to fibrous cap rupture or superficial erosion. Fibrous cap rupture causes STEMI more commonly than NSTE-ACS, whereas eroded lesions are more frequently associated with NSTE-ACS70. Fibrous cap rupture is identified on OCT by the presence of a discontinuity in the fibrous cap that is associated with a cavity inside a lipid-rich plaque (Figure 5A, Figure 5B)71. Although plaque rupture is the most frequent finding in ACS, pathological studies have demonstrated the presence of plaque erosion in about 20-30%, mostly in NSTE-ACS patients (Figure 5C)72. Plaque erosion may be defined as “definite” by the presence of attached thrombus overlying an intact and visualised plaque or “probable” when there is luminal surface irregularity at the culprit lesion in the absence of thrombus or when there is attenuation of underlying plaque by thrombus without superficial lipid or calcification immediately proximal or distal to the site of thrombus7273. A calcified nodule (CN) with thrombus has also been suggested as a cause of ACS on intracoronary imaging (Figure 5D). A CN is defined as fibrous cap disruption detected over a calcified plaque, characterised by protruding calcification, superficial calcium, and the presence of substantive calcium proximal and/or distal to the lesion72.

Intravascular imaging (IVI), particularly OCT, may have a crucial role in identifying plaque-induced events. Moreover, due to its ability to discriminate between plaque rupture and erosion, OCT may be a valuable tool to guide treatment strategies, by deferring stenting in non-critical stenoses with plaque erosion74.

Furthermore, without IVI, mild culprit plaques, intraplaque cavities, and layered plaques, which are hallmarks of culprit lesions, may be overlooked, especially when early initiation of antithrombotic therapies and endogenous thrombolysis dissolve a superimposed thrombus. Beyond detecting acute culprit lesions, OCT can identify high-risk plaque features or “vulnerable plaques” such as thin-cap fibroatheromas (TCFAs), high lipid burden plaques, and macrophage infiltration, which may predispose patients to future ACS. In a selected patient population, their identification may be of clinical significance, prompting a need for PCI75. In the CLIMA Study, when all four predefined high-risk plaque features (minimum lumen area <3.5 mm2, TCFA with a cap thickness <75 μm, lipid arc >180°, and macrophage infiltration) were present, the hazard ratio for the primary hard endpoint (cardiac death or target segment MI) was as high as 7.5476. Supporting this concept, the PREVENT trial77 demonstrated that preventive PCI of non-flow-limiting (fractional flow reserve [FFR]>0.80), vulnerable plaques significantly reduced MACE compared to optimal medical therapy alone. These findings suggest that PCI may have a role even in angiographically non-obstructive, but imaging-defined, high-risk lesions, warranting further exploration of this proactive strategy.

Figure 5. Plaque-induced causes of NSTE-ACS. A) Plaque rupture with discontinuity in the fibrous cap (white arrow). B) Necrotic core in the same patient, localised proximally to the plaque rupture (yellow arrow). C) Plaque erosion (asterisks). D) Calcified nodule (asterisk). NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome

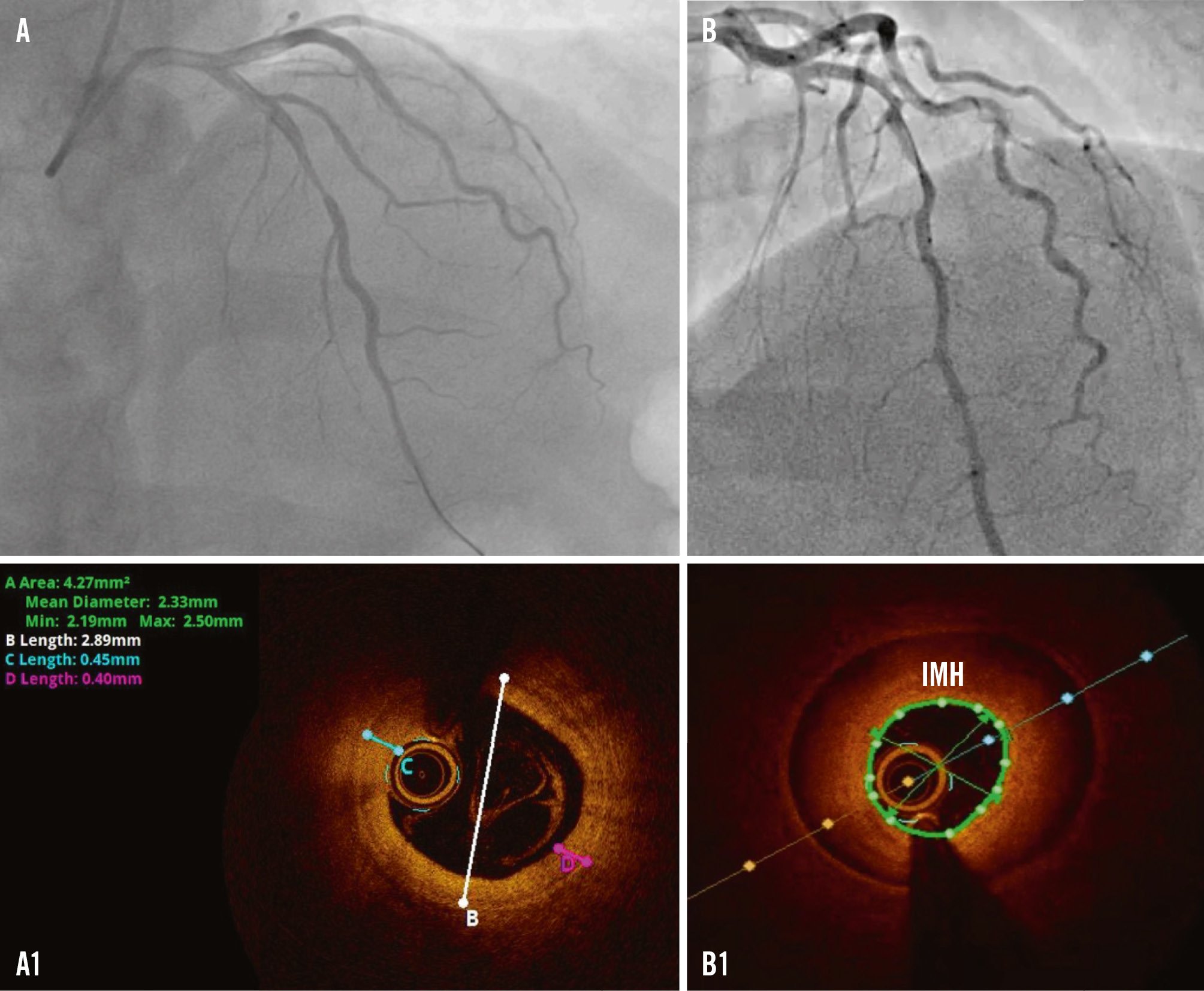

Non-plaque-induced events as a mechanism of MI with non-obstructive coronary arteries

The underlying mechanism of MINOCA, however, besides plaque-induced events (plaque rupture, erosion, or calcified nodule), can include non-plaque-induced events such as epicardial vasospasm, coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), or spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) (Figure 6). If the underlying cause of MINOCA is not established using ICA alone, further evaluation using left ventriculography, IVI, and “functional coronary angiography” (referring to the combination of ICA with adjunctive tools for CMD and vasoreactivity testing) can be useful to identify the underlying cause (Figure 3). OCT or IVUS may help in identifying SCAD, particularly type 2b, which closely mimics atherosclerosis and may be easily overlooked without confirmation of an intramural haematoma by these imaging modalities (Figure 6B, Figure 6B1)78. When OCT is inconclusive or an identifiable culprit lesion is not found, invasive tests for CMD or coronary vasospasm may be considered. Ultimately, a non-invasive investigation, preferably with CMR, is recommended1.

In the HARP-MINOCA registry, of 145 MINOCA patients, a definite or possible culprit lesion was identified by OCT in 46.2%, with plaque rupture as the leading cause79. Intimal bumping – defined as smooth, localised intimal protrusions, typically without fibrous cap disruption, often resolving with intracoronary nitroglycerine – was described as a marker of coronary artery spasm in 2% of patients with an identifiable culprit lesion. In contrast, SCAD was detected in only 0.7%, as it was a prespecified exclusion criterion79. Based on OCT alone, about half of the patients remained with an undefined diagnosis. However, among 116 patients who underwent CMR (cine imaging, LGE, and T2-weighted imaging and/or T1 mapping), an underlying aetiology could be determined in 74.1% of patients, with an ischaemic pattern in 53.4% and a non-ischaemic pattern (mostly due to myocarditis, Takotsubo syndrome, or non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy) in 20.7% of patients79. When CMR was used in addition to OCT, it resulted in 84.5% of cases with identifiable causes of MINOCA79.

Figure 6. Non-plaque induced events in NSTE-ACS. A) Significant stenosis in the mid-LAD in a patient with chest pain, ECG changes and a positive troponin result. A1) OCT finding after intracoronary NTG administration revealing intimal thickening of 0.45 mm and intimal bumping suggestive of spasm. B) Coronary angiogram in a patient with NSTEMI presentation. B1) OCT revealing an IMH in the distal and mid-LAD suggestive of SCAD type 2b. ECG: electrocardiogram; IMH: intramural haematoma; LAD: left anterior descending artery; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; NTG: nitroglycerine; OCT: optical coherence tomography; SCAD: spontaneous coronary artery dissection

NSTE-ACS with multivessel disease

Culprit-only versus complete revascularisation

Approximately half of NSTE-ACS patients have MVD, which leads to a dilemma regarding the revascularisation strategy that should be chosen: complete versus culprit-only PCI. If complete revascularisation is chosen, should it be a single-staged or multistaged procedure33580? Currently, there is a lack of sufficient evidence supporting the benefits of complete revascularisation in NSTE-ACS. Some observational studies and meta-analyses have indicated that complete revascularisation in NSTE-ACS patients with MVD is linked to reduced mortality and MACE compared to a culprit-only strategy8182. Others, however, suggest that multivessel PCI at the index procedure may be considered to prevent unplanned revascularisations, but that this has no influence on mortality8384.

To date, the SMILE trial is the only RCT in this field to have concluded that single-staged PCI in NSTE-ACS patients is superior to multistaged PCI. However, it does not address whether multivessel PCI is beneficial to culprit-only PCI at the index procedure nor does it assess the added value of functional evaluation of non-culprit lesions85. Current ESC guidelines recommend considering complete revascularisation (Class IIa, LoE C), preferably during the index procedure, especially in haemodynamically stable patients, based on individual clinical profiles and comorbidities1. The ongoing COMPLETE-2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05701358) of physiology-guided versus angiography-guided non-culprit lesion complete revascularisation strategies in patients with AMI (STEMI and NSTEMI) and MVD and the COMPLETE-NSTEMI trial86 of culprit-lesion only versus complete revascularisation in NSTEMI might provide valuable insights concerning revascularisation strategies.

Functional assessment of non-culprit lesions

The evaluation of non-IRA lesion severity in NSTE-ACS poses additional challenges. Acute myocardial ischaemia can exaggerate the apparent severity of non-IRA lesions when assessed via angiography, necessitating functional evaluation tools like FFR or instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR). It is well known that angiography alone is inaccurate in assessing the functional significance of coronary stenosis when compared with FFR87. Studies, including subanalyses of trials like FAME and FAMOUS NSTEMI, have shown that incorporating FFR into the decision-making process can refine the revascularisation strategy by identifying functionally significant lesions, potentially avoiding unnecessary interventions, and using fewer stents and less contrast medium878889. The PRIME-FFR registry included 533 ACS patients and reported that a management strategy guided by FFR is associated with a high reclassification rate, changing the management strategy in 38% of cases (e.g., from CABG to PCI or to medical treatment), without an impact on MACE, death/MI, or angina symptoms at 1 year, and was thus found to be safe90.

Despite this evidence of the feasibility and utility of functionally guided revascularisation in NSTE-ACS with MVD, functional assessment during the acute phase of NSTE-ACS may still be unreliable because of transient microvascular dysfunction. Thus, delayed assessments could offer more precise evaluations. The ESC guidelines note that functional invasive evaluation of non-IRA lesions during the index procedure is a Class IIb recommendation, suggesting it may be considered in selected cases1.

Specific populations

Management of older adults with NSTE-ACS

Due to the ageing of the global population, there is an increasing number of older individuals presenting with NSTE-ACS, with NSTEMI being the most common ACS diagnosis91. The management of this specific subset of patients necessitates a delicate approach due to a higher prevalence of comorbidities, frailty, and increased bleeding and ischaemic risks. Older adults (≥75 years) are often underrepresented or excluded from many pivotal ACS clinical trials, which weakens the practice of evidence-based medicine in this high-risk cohort92.

Moreover, one of the most powerful predictors of adverse outcomes following ACS is age, with a 15.7-fold increased odds of in-hospital mortality in patients ≥85 years old compared to those <45 years old93. Yet, older patients are less likely to receive evidence-based therapy, compared to younger patients, suggesting a “risk-treatment” paradox in current clinical practice209294. Older age, frailty, comorbidities, cognitive status, anticipated complex calcified lesions on angiographic findings, and life expectancy may influence the decision on the choice of antithrombotic therapy and invasive strategy959697.

RCTs in older patients with NSTE-ACS

RCTs in older patients with NSTE-ACS are faced with problems of slow enrolment, a small number of patients, lack of power, and the exclusion of those with comorbidities, frailty, or high procedural risk. Until recently, there were only six RCTs investigating invasive strategy in older patients with NSTE-ACS92, with the largest one being the After Eighty Study that included 457 patients (mean age 85 years, females representing 50.8%)98. The trial showed a benefit in primary endpoint reduction in the early revascularisation group compared to the selective invasive strategy (40.6% vs 61.4%; HR 0.53, 95% CI: 0.41-0.69; p<0.0001). This outcome was mainly driven by the reduction of MI and unplanned revascularisation, with no influence on mortality98. However, 90% of screened patients were excluded for unknown reasons, thus limiting the generalisability of findings to a real-world population.

Meta-analysis in older patients with NSTE-ACS

A meta-analysis by Garg A et al, including six RCTs (two of them specifically designed for the older population) with 1,887 patients, confirmed that a routine invasive strategy is superior to selective invasive management for reducing MI risk, but not mortality, in older patients with NSTE-ACS99. Similarly, in an individual patient meta-analysis conducted by Kotanidis et al, which included six RCTs with 1,479 participants, no evidence was found that routine invasive treatment for NSTE-ACS in older patients reduces the risk of a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality and MI within 1 year compared with selective invasive management. However, there is convincing evidence that invasive treatment significantly lowers the risk of repeat MI or urgent revascularisation100.

SENIOR-RITA Trial

Recently, the largest RCT in this patient cohort − SENIOR-RITA − was published, involving 1,518 patients with NSTEMI, aged ≥75 years (mean age 82 years, 45% females), who were randomised to a conservative strategy or an invasive strategy. Patients who were frail or had a high burden of coexisting conditions were eligible. An invasive strategy did not result in a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular death or non-fatal MI (the composite primary outcome), compared with a conservative strategy, over a median follow-up of 4.1 years101. There was a significant reduction in non-fatal MI (HR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.57-0.99) and in subsequent coronary revascularisation (HR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.17-0.39) in patients undergoing invasive management. The study also included assessments of frailty, cognition, comorbidity, and quality of life as secondary outcome measures, emphasising the need for individualised care102103.

Assessment of frailty, comorbidity, and cognition in older adults

To aid in decision-making, routine assessment of frailty (e.g., Rockwood Frailty Score or Fried Frailty Index), comorbidity (e.g., Charlson Index), and cognitive impairment (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment) in ACS patients is recommended to further enhance care by balancing the benefits and risks of intervention and ensuring patient-centred management104105106. Frailty assessments and individualised risk evaluations are critical to guide decision-making. Ultimately, appropriate holistic assessment to guide the treatment of older, frail patients with NSTE-ACS will impact health-related quality of life104.

Management of prior CABG patients

Patients with previous CABG surgery account for ~10% of patients presenting with NSTE-ACS and often represent a high-risk subgroup, as they are typically older, have greater comorbidities, and have increased mortality compared to those without prior CABG107. Clinical guidelines currently recommend a routine early invasive strategy in NSTE-ACS patients identified as high risk (e.g., GRACE score >140), with ICA as the standard of care for those meeting such criteria3. From a patient perspective, ICA is more challenging in a post-CABG patient and is associated with a greater risk of complications such as contrast-induced acute kidney injury and stroke108109. Furthermore, when ICA is performed, patients with prior CABG are less likely to receive PCI110111112113, implying a lower likelihood of treatment benefit with a routine invasive strategy.

Whilst observational evidence suggests that there is a benefit with revascularisation in reducing MACE for patients with prior CABG who present with NSTE-ACS compared with medical therapy, national registries consistently demonstrate that CABG patients are less likely to undergo angiography than patients without prior CABG107113. Pivotal clinical trials that have compared routine invasive management versus selective invasive management in ACS, for example, TIMI IIIB114, FRISC-II21, VINO115 and RITA 323, all excluded patients with prior CABG, and other trials that included these patients only involved small numbers. The only dedicated RCT of invasive versus medical management of NSTE-ACS in CABG patients reported similar MACE outcomes at 2 years, although this trial only included 60 patients112. A recent meta-analysis of the outcomes of 897 CABG patients from 11 RCTs of a routine invasive versus a selective invasive strategy in NSTE-ACS, including previously unpublished subgroup outcomes of nine trials, demonstrated that a routine invasive strategy does not reduce mortality (RR 1.12, 95% CI: 0.97-1.29) or MI (RR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.65-1.23)116. Therefore, larger, dedicated RCTs are needed to compare invasive and non-invasive approaches in prior CABG patients presenting with NSTE-ACS117. One potential consideration in the design of any study would be the use of CCTA as the first-line test in patients with prior CABG presenting with NSTE-ACS, given its known excellent sensitivity and specificity for assessing bypass grafts; if grafts are found to be patent, the higher risks of invasive angiography can be avoided. CCTA can also help target the use of PCI, an approach that has recently been demonstrated to reduce MACE in the BYPASS-CTCA trial, which included a 45% NSTEMI cohort118.

Females presenting with NSTE-ACS

CAD represents >50% of cardiovascular deaths among females, and over a third of all females in their fourth decade will develop some degree of CAD119. Despite the high prevalence of CAD in females, the female population is underrepresented in almost all clinical trials, including heart failure, CAD, and ACS119120121. Although current ESC guidelines do not support distinctive management of ACS based on sex, several studies have reported that significant sex disparities exist in the management of patients with NSTE-ACS122123124. Females presenting with ACS, both STEMI and NSTEMI, suffer higher in-hospital mortality than males125.

Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of females with NSTE-ACS

Females who suffer ACS typically present for medical assessment later than males, and they are less likely to undergo ICA and PCI within the guideline-directed therapeutic window. Fewer females are offered cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programmes following an acute coronary event126127. Females comprise almost 50% of patients with MINOCA compared to ~25% of patients with MI with obstructive CAD128. Although previous studies have shown that MINOCA is associated with fewer in-hospital complications and better clinical outcomes compared to MI with obstructive CAD129, when it comes to sex, the rates of mortality are significantly higher in females than in males in both clinical scenarios130.

NSTE-ACS in older females

Older females with NSTE-ACS represent a unique and particularly delicate subset of patients to manage, given their significant underrepresentation in RCTs. A meta-analysis by Rubino et al131 included 717 females with a median age of 84 years from six RCTs comparing invasive and conservative management strategies in NSTE-ACS. The study concluded that in this population, an invasive management strategy does not significantly reduce the composite outcome of all-cause mortality or MI at 1-year follow-up. However, invasive strategies were found to significantly reduce the risk of MI (HR 0.49, 95% CI: 0.32-0.73; p<0.001) and urgent revascularisation (HR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.20-0.98; p=0.04).

Early versus delayed invasive strategy in females

A meta-analysis by Mills et al132 evaluated six RCTs involving 2,257 females with a median age of 69 years. The study concluded that an early invasive approach (median time 5 hours) did not confer significant benefits in reducing the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality and MI compared to a delayed strategy (median time 49 hours). However, it was effective in reducing recurrent ischaemia. Importantly, high-risk females, as identified by a GRACE score >140, who underwent early invasive management experienced a significant reduction in the hazard for all-cause mortality and MI at 6 months (HR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.45-0.94; p=0.021; p-interaction=0.035).

Future directions for addressing female underrepresentation and improving NSTE-ACS management

Existing studies highlight the ongoing issue of underrepresentation of females in clinical trials, with an average participation rate of ~25%, which leads to their underdiagnosis and undertreatment. Addressing this gap requires prioritising the enrolment and retention of females in future, rigorously designed clinical trials to generate sex-specific data on the efficacy and safety of NSTE-ACS treatments. Additionally, addressing disparities in care, research, and prevention necessitates dedicated sex-specific research to elucidate pathophysiology, outcomes, and effective interventions for females. Establishing sex-specific guidelines for the management of NSTE-ACS and broader cardiovascular care in females is crucial. Implementing these strategies holds the potential to markedly improve NSTE-ACS management in females, aligning with the Lancet Commission’s goal of reducing the global cardiovascular burden by 2030133.

Antithrombotic therapy in NSTE-ACS – a brief overview

Dual antiplatelet therapy

In NSTE-ACS, a dual antithrombotic approach combining antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies is crucial to mitigate thrombotic risks and enhance patient outcomes. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) remains a cornerstone, typically initiated with a loading dose of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA; 150-300 mg orally or 75-250 mg intravenously, Class I) and a potent P2Y12 inhibitor such as ticagrelor or prasugrel, while clopidogrel should be used where newer potent agents are contraindicated/not available, or in some patients considered at high bleeding risk (HBR)1134.

P2Y12 inhibitor pretreatment

The approach to antithrombotic therapy in NSTE-ACS has evolved, particularly regarding the timing and selection of P2Y12 inhibitors. Earlier guidelines3135 recommended P2Y12 inhibitor pretreatment (loading dose prior to coronary angiography) for all patients at high risk of coronary events. This strategy was guided by trials indicating reduced thrombotic events; however, there was an elevated bleeding risk in patients ultimately not requiring PCI136137. The latest ESC guidelines1 revised this approach, emphasising the deferral of P2Y12 inhibitor initiation until coronary anatomy has been defined by coronary angiography. This change reflects data from studies such as ACCOAST, which demonstrated that among patients with NSTE-ACS who were scheduled to undergo ICA, pretreatment with prasugrel (with a median time from loading dose to ICA of 4.4 h) increased the rate of major bleeding complications without significantly improving ischaemic outcomes138.

Regarding the choice between ticagrelor and prasugrel, the largest head-to-head comparison of 1-year DAPT with prasugrel versus DAPT with ticagrelor in patients with ACS planned for invasive evaluation − the ISAR-REACT 5 trial − found that a ticagrelor-based strategy with routine pretreatment was inferior to a prasugrel-based strategy with a deferred loading dose in NSTE-ACS patients139. Therefore, in patients with a working diagnosis of NSTE-ACS, routine pretreatment with a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor in patients anticipated to undergo an early (<24 h) invasive strategy is not recommended (Class III)1. However, if there is an anticipated delay to ICA (>24 h), pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor may be considered according to the bleeding risk of the patient (Class IIb, LoE C)1. In patients proceeding to PCI without P2Y12 inhibitor pretreatment, a loading dose is recommended at the time of PCI, with prasugrel preferred over ticagrelor1. On the other hand, for patients managed conservatively, initiation of DAPT, including a P2Y12 inhibitor, can be performed promptly upon diagnosis, guided by the balance between ischaemic and bleeding risks. This shift towards selective pretreatment aligns with the goal of reducing unnecessary bleeding risk while maintaining ischaemic protection.

Intravenous antiplatelet therapy

In patients with NSTE-ACS undergoing PCI who are P2Y12 inhibitor-naïve or unable to receive oral therapy (e.g., intubated or in cardiogenic shock), cangrelor, a short-acting intravenous P2Y12 inhibitor, may be considered (Class IIb, LoE A)1 to reduce periprocedural ischaemic events. Its use is advised on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the increased risk of minor bleeding and limited supporting data when used alongside prasugrel or ticagrelor. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (e.g., eptifibatide or tirofiban) are not recommended for routine use due to bleeding risk and lack of ischaemic benefit in the era of potent oral antiplatelets, but they should be considered (Class IIa, LoE C) as bailout therapy in selected cases of large thrombus burden, no-reflow, or slow flow during PCI1.

Parenteral anticoagulant therapy

Patients with NSTE-ACS are also recommended to receive parenteral anticoagulant therapy. Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is recommended for patients undergoing immediate or early ICA (Class I), but enoxaparin should be considered (Class IIa) as an alternative to UFH, especially in cases where monitoring of clotting times is complex140. For patients who are not anticipated to undergo early angiography, fondaparinux (with a UFH bolus at time of PCI) is recommended (Class I) in preference to enoxaparin141, although enoxaparin should be considered if fondaparinux is not available. Additionally, after much controversy, the recent individual patient data meta-analysis of over 12,000 NSTEMI patients across five large RCTs concluded that bivalirudin significantly reduces serious bleeding and yields similar outcomes to UFH142.

Duration of antithrombotic therapy

Concerning the duration of antithrombotic therapy, while continuation of anticoagulation after PCI is not necessary unless an indication for lifelong oral anticoagulation (OAC) is present, post-PCI antiplatelet treatment is mandatory in ACS patients. A default DAPT regimen consisting of a potent P2Y12 inhibitor (prasugrel or ticagrelor) and ASA is generally recommended for 12 months (Class I)1. However, maintaining DAPT long term may be associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Therefore, to mitigate bleeding risk while attaining optimal ischaemic protection, de-escalation strategies, including ASA discontinuation (abbreviated DAPT regimen) or switching between P2Y12 inhibitors, have been investigated. Several RCTs evaluated DAPT duration by testing “ASA-free” therapies, consisting of P2Y12 inhibitor (ticagrelor) monotherapy after a short course (typically 1-3 months) of DAPT143144145146147148. These trials provide evidence that discontinuing ASA within 1 to 3 months post-ACS significantly reduces bleeding risk without increasing ischaemic events, particularly in HBR patients. This strategy has therefore received a Class IIa recommendation in the ESC guidelines1. In contrast, the ACC/AHA guidelines assign a Class I, LoE A recommendation to the transition to ticagrelor monotherapy ≥1 month after PCI, recognising its usefulness in reducing bleeding risk54. Furthermore, in the recently published TARGET-FIRST trial149 of low-risk MI patients who completed one month of uneventful DAPT and underwent early complete revascularisation within 7 days of the index MI, P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy for the remaining 11 months was non-inferior to standard DAPT in ischaemic outcomes and superior in reducing bleeding, suggesting that abbreviated DAPT may be particularly compelling in low-risk, completely revascularised patients. Conversely, the NEO-MINDSET Trial150 showed that very early ASA cessation (within 7 days post-PCI in ACS patients) did not meet non-inferiority criteria for ischaemic endpoints, although it was associated with a lower incidence of bleeding. Another de-escalation approach, though less extensively studied, involves switching from potent P2Y12 inhibitors (ticagrelor or prasugrel) to clopidogrel after the first month151152. This strategy is based on the fact that ischaemic risk is highest during the initial month post-ACS and subsequently declines, while bleeding risk remains unchanged over time. According to the current guidelines, this strategy of switching therapies may be considered (Class IIb) in HBR patients1151153. Guided approaches using platelet function testing or genotyping may further personalise therapy. Trials such as TROPICAL-ACS152 and POPular Genetics153 have demonstrated that de-escalation guided by platelet-function testing or a CYP2C19 genotype is non-inferior to standard therapy in preventing ischaemic events, with reduced bleeding. A recent meta-analysis by Galli et al154 further supports this approach, demonstrating that outcomes vary depending on the strategy employed: de-escalation led to a significant reduction in bleeding without compromising efficacy, while an escalation approach was associated with a significant reduction in ischaemic events without a trade-off in safety. These findings highlight the potential utility of personalised antiplatelet strategies in specific clinical scenarios to optimise both safety and effectiveness. After 1 year of DAPT, ASA monotherapy is the recommended strategy1. However, in patients with high ischaemic risk but without HBR, prolonged antithrombotic strategies with a reduced dose of ticagrelor (60 mg bid)155 or low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg bid) added to ASA156 may be considered (Class IIa)1. Another emerging option for long-term secondary prevention is clopidogrel monotherapy, which demonstrated superiority over ASA in reducing the composite of thrombotic and bleeding events in the HOST-EXAM trial157.

NSTE-ACS patients who require oral anticoagulation

In patients with NSTE-ACS who require OAC, antithrombotic therapy should be carefully tailored to balance ischaemic and bleeding risks. Triple antithrombotic therapy − consisting of ASA, clopidogrel, and an oral anticoagulant − is recommended for the shortest duration possible, typically for up to 1 week. Thereafter, dual antithrombotic therapy (OAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor) is generally preferred for up to 12 months1. Withdrawing antiplatelet therapy at 6 months while continuing OAC may be considered in selected cases with HBR1. Beyond this period, monotherapy with OAC is usually continued1. Furthermore, the choice of OAC should consider the patient’s renal function and the specific clinical scenario, with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) preferred over vitamin K antagonists in most cases because of their superior safety profiles1. Regular reassessment of bleeding and thrombotic risks is essential to adjust the therapy appropriately over time.

Contemporary challenges and future perspectives

Despite substantial advancements in the diagnosis and management of NSTE-ACS, several evolving concepts continue to challenge traditional paradigms and may influence future clinical practice.

One such development is the growing interest in reclassifying acute coronary syndromes based on the presence or absence of acute coronary occlusion – shifting from the conventional STEMI/NSTEMI terminology to a more pathophysiological framework of “occlusion MI” (OMI) versus non-OMI158. While promising, this terminology is not yet integrated into clinical workflows, as ECG findings remain central to early decision-making.

Another major challenge is the differentiation between myocardial infarction and myocardial injury, particularly in the context of elevated hs-cTn levels. As the widespread use of hs-cTn assays has led to increased detection of minor myocardial damage, clinicians are increasingly faced with distinguishing Type 1 MI (plaque-related) from Type 2 MI (supply-demand mismatch) or non-ischaemic myocardial injury. This diagnostic complexity often complicates treatment decisions, as current guidelines focus primarily on Type 1 MI.

Finally, the clinical relevance of UA is diminishing. With improved biomarker sensitivity, true UA is now rare, and its continued classification within NSTE-ACS is being questioned.

Together, these shifts highlight the need for refined diagnostic algorithms and further research to better align terminology, risk stratification, and management strategies with contemporary practice.

Conclusions

This review underscores the complexity of managing NSTEMI due to its diverse presentations and underlying pathophysiology. Advances in diagnostic tools, such as hs-cTn and risk stratification models, have improved early detection and individualised treatment planning. However, challenges persist, such as variability in applying routine invasive versus selective invasive strategies and the timing of interventions. Current evidence favours routine invasive strategies for high-risk patients, while selective approaches may suffice for those with lower risk. Moreover, emerging diagnostic methods, such as CCTA and CMR, alongside intravascular imaging, have refined the identification of culprit lesions, particularly in conditions like MINOCA. Special considerations for older patients and female patients emphasise the need for tailored approaches, accounting for frailty, comorbidities, and underrepresentation in clinical trials.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest with regard to this manuscript to declare.