Abstract

Objective: During open heart surgery, the myocardium usually provides sufficient visual contrast with both epicardial veins and arteries. However, visibility of coronary arteries may occasionally be impaired due to, e.g., intra-myocardial course of coronary arteries, increased epicardial fat, epicardial post-surgical adhesions, or pericarditis. Seen within the near infra-red range, coronary arteries show higher contrasts in relation to the myocardium than coronary veins. Hence, we developed a non-contact stereo-optical camera to selectively enhance coronary arteries by combining visible and near infra-red images. In this paper we present our first results on porcine and human hearts.

Materials and methods: Two CMOS-cameras, with apochromatic lenses and dual-band LED-arrays, captured visible colour (visible range, or VIS, 400-780nm) and near infra-red grey-scale (near infra-red range, or NIR, 910-920nm) images by sequentially switching between LED-array emission bands. Data was recorded by computer and processed off-line. Arterial NIR contrasts were algorithmically distinguished from shadows and specular reflections. Detected arteries were selectively enhanced and back-projected into the stereoscopic VIS-colour-image using either a 3D-display or conventional shutter glasses.

Results: Our technique visualised coronary vasculature and allowed to identify concealed parts of coronary arteries using off-line processing. Raw VIS & NIR images were real-time, processing took < 15s after filming.

Conclusion: The applied principle works, but needs further development.

Introduction

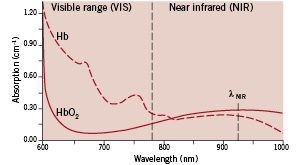

For visually guided procedures like cardiac surgery, it is obvious that a good view onto a well lighted operating field is crucial. A well lighted myocardium usually forms a sufficiently contrasting background for the dark coronary veins and for the lighter coronary arteries. In this regard, most of the coronary arteries can be readily identified. In some instances – such as the intra-myocardial course of coronary arteries, increased epicardial fat, epicardial adhesions after previous surgery, or pericarditis – visibility of the coronary arteries may be impaired. When, however, extending vision beyond the boundaries of the human eye into the near infra-red, this situation is changed: visual penetration depth is increased and coronary arteries show an improved contrast against the myocardium which even dominates compared with the coronary veins. This is caused by the different optical properties of haemoglobin and oxyhaemoglobin as illustrated in Figure 1.2,4,10,12

Figure 1. Spectral absorption curves for haemoglobin (Hb) and oxyhaemoglobin (HbO2)

The wavelength axis shows the spectral range from 600 nm (visible reddish orange) to 1000 nm (invisible infra-red). The boundary between the visible range (VIS) and near infra-red (NIR) lies at 780 nm. The vertical scale indicates the degree of light absorption. Within the visible range, highly oxygenated blood absorbs less red light than poorly oxygenated blood, which explains the bright red appearance of arterial blood.

Within the near infra-red, absorption is significantly lower and thus the light can penetrate deeper. For the applied wavelength λNIR of 920 nm, highly oxygenated blood absorbs stronger than poorly oxygenated blood.

We previously described a new non-contact optical technique that allows selective enhancement of superficial blood vessels beneath the skin by combining images obtained in the visible range (VIS) with images obtained in the invisible near infra-red range (NIR)8. We added a “surgical mode” to the image processing software of this device to utilise differences in blood oxygenation levels to enhance the visualisation of coronary arteries. By filming pigs’ hearts, the method was fine-tuned to a level that could be handled in a clinical environment. This article describes our first recordings during human cardiac surgery.

Methods

Instrumental set-up

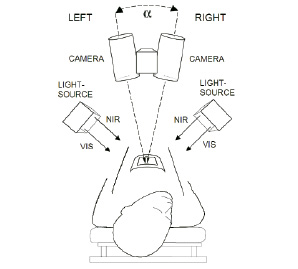

The instrumental hardware front-end set-up is schematically drawn in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Device principle. Two identical cameras, set apart at normal eye distance (7 cm), are aligned at an angle (similar to the human eye) and focused on the heart. Both cameras capture colour images within the visible range (VIS, 400-780 nm) but also grey-scale images within the near infra-red range (NIR, 910-920 nm). This is achieved by sequentially switching between the VIS and NIR LED-array emission bands. The information contained in both image-types is then selectively combined by software.

Two custom built synchronised identical single-chip CMOS-cameras (Vector Technologies Belgium) were equipped with apochromatic lenses and specially constructed dual-band LED-arrays. These LED-arrays were current controlled and had individually programmable channels for the emission of visible white light (with an adjustable colour temperature) as well as for the emission of near infra-red radiation. The light sources were carefully constructed so that the geometrical beam profiles of VIS and NIR matched very closely. Any resulting shadows and/or reflections thus also matched for both spectral ranges, which allowed adequate discrimination between contrasts originating from the tissue surface versus contrasts originating from within the tissue7. Cameras and light sources were placed on a custom made balanced mechanical support with six adjustable joints. The cameras were capable to obtain normal colour images within the visible range, but additionally were sensitive to near infra-red radiation, which was achieved by a special NIR-transparent RGB filter mosaic on the camera-chip. By sequentially switching between emission bands of the LED-arrays, pixel-to-pixel aligned images within the visual range (VIS, 400-780 nm) and near infra-red range (NIR, 910-920 nm) were acquired. Left (L) and right (R) image data was simultaneously acquired by 2 dedicated image acquisition boards and streamed to a dual 3.06 GHz Xeon-processor PC equipped with a high-speed SATA-disk array and 2Gb of RAM. The images were processed by custom software and either presented on an auto-stereoscopic Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) monitor or on a normal Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) monitor equipped with LCD-shutter glasses.

Data acquisition

Multi-spectral stereoscopic movies were recorded during cardiac surgery with the sterile packed stereo camera located at a distance of approximately 45 cm from the heart (see figure 3).

Figure 3. The device in practice. A cart with the device was placed near the head-side of the patient support, the stereo-camera was positioned on an adjustable balanced arm, thus avoiding interference with the surgical procedure. Normal disposable transparent sterile covers were applied. Average recording distance was 45 cm.

Real-time raw VIS and NIR images were available from a preview mode which allowed for aiming, adjustment of converging angle  and focus of the cameras. Software triggering the cameras then streamed all raw image data via the image acquisition boards to the PC, which automatically saved all this raw image data in 8 bit encoding depth on a fast SATA hard disk array, together with the applied camera and light source settings.

and focus of the cameras. Software triggering the cameras then streamed all raw image data via the image acquisition boards to the PC, which automatically saved all this raw image data in 8 bit encoding depth on a fast SATA hard disk array, together with the applied camera and light source settings.

Data processing

The stored raw image data was subjected to post-processing using custom developed software (programming language C++) which facilitated viewing the contrast information contained in visible and infra-red light in a combined image7. The processing method allowed discrimination between image information obtained from the tissue surface versus image information obtained from shallow depth within the tissue. Additionally, the difference in spectral absorption (see Figure 1) between haemoglobin (Hb) and oxyhaemoglobin (HbO2) was exploited to selectively enhance the coronary arteries using the ratio between the intensity of the visible red and invisible infra-red pixel values as a decision criterium on whether or not to enhance a pixel.

Data presentation

The images could either be displayed on an auto-stereoscopic LCD-monitor (Sharp LL-151-3D) or on a CRT-monitor (Iiyama Vision Master 21) equipped with shutter glasses (e-Dimensional). The post-processing software offered the possibility for pause and scrolling forward or reverse frame-by-frame. The user could freely switch between stereoscopic (3D) or monoscopic (flat) display of normal colour view (VIS), grey scale near infra-red view (NIR) or a combined virtual reality view (VR). By means of virtual slider controls and virtual push buttons, settings for shadow suppression, noise threshold and blood vessel contrast could be adjusted.

Results

Results obtained with pigs’ hearts

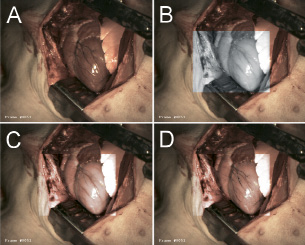

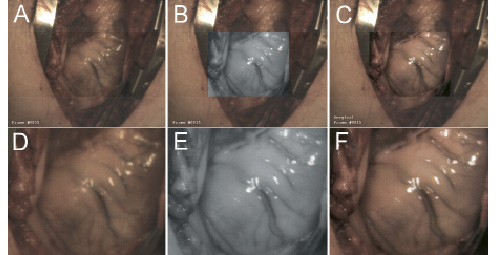

The method was developed using movies acquired during cardiac surgery on pigs, in conformance with the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and under the regulations of Erasmus MC Rotterdam. Figure 4a shows the normal VIS image of a pigs’ heart. The myocardium forms a visually well contrasting background for the dark coronary veins and a somewhat less contrasting background for the lighter coloured coronary arteries. Figure 4b shows, that beyond the boundaries of the human eye, in the near infra-red range this situation is changed; the coronary arteries show a higher contrast against the myocardium than the coronary veins.

Figure 4. Example of results for pigs’ hearts. Normal visual (VIS) image of a pigs’ heart (fig. 4a) compared to a near infra-red (NIR, 920 nm) image within a centred region of interest reveals an improved contrast for the epicardial arteries (fig. 4b). Selective combination of VIS and NIR vascular contrasts results in an improved visualisation of the epicardial arterial diagonal branches (fig. 4c). Adjusting the software parameters so that venous contrasts from the VIS image are also preserved combines the best vascular contrasts of both spectral ranges (fig. 4d). The veins in fig. 4d look thinner than those in fig. 4b. Also the diagonal branches of the epicardial arteries do not completely overlap when comparing the VIS (fig. 4b) and NIR (fig. 4c) images. These effects are caused by heart motion during the interval between VIS and NIR exposure (due to the relatively low frame-rate).

In figure 4c this information has been incorporated within the visible image, which drastically improves arterial contrasts but decreases venous contrasts. Finally, figure 4d contains the “best of both worlds”, by combining the VIS venous contrast and the NIR arterial contrast in one virtual reality (VR) image. Some motion artifacts are present in figure 4d, which are caused by the time interval between the VIS and NIR acquisition. This can be solved by increasing the frame rate and/or by using parallel acquisition of both wavelength ranges instead of the applied sequential image acquisition which was used here.

Results for human hearts

Figure 5 shows results obtained during our first recordings of a human heart.

Figure 5. Results of our first recordings of a human heart. Figure 5a presents a full overview captured in the visible range (VIS). In figure 5b (NIR) and 5c (enhanced) the centred region of interest are displayed framed within a larger overview captured in the visible range. Figure 5d zooms in on the centred ROI in VIS-mode, whereas figure 5e shows the zoomed ROI in NIR-mode and figure 5f displays the zoomed ROI in enhanced mode. Although these first recordings were not optimally focused, it is clear that the VIS image (fig. 5a & 5d) contains less vascular contrast than the NIR image (fig. 5b & 5e). The resulting combined image (fig. 5c & 5f) clearly shows two vessels (whereas fig. 5a & 5d only show one).

Within the visual range, the fat layer around the heart decreases the visibility of coronary vasculature (see figure 5a for overview and figure 5d for zoomed region of interest, or ROI). The NIR image, however, reveals more of the vascular pattern (see figure 5b for NIR-mode ROI in VIS-overview frame and figure 5e for zoomed NIR-mode ROI). The combined information results in an enhanced image (see figure 5c for enhanced ROI in VIS-overview frame and figure 5f for zoomed enhanced ROI).

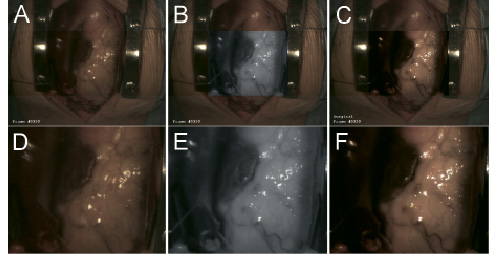

Figure 6 shows results from another patient, after implementation of a few small mechanical camera modifications.

Figure 6. Typical results viewing epicardial fat on a human heart. The upper row of figures shows the centred region of interest, 6a (VIS), 6b (NIR) and 6c (enhanced), framed within a larger overview captured in the visible range. Within the lower row of figures, only the corresponding centred regions of interest are shown 6d (VIS), 6e (NIR) and 6f (enhanced). Two blood vessels already contrasting fairly well within the VIS image (fig. 6a & 6d) appear more pronounced in the NIR image recorded at a wavelength of 920 nm (fig. 6b & 6e). Also here, processing clearly enhances vascular visualisation (fig. 6c & 6f).

Discussion

These first results are encouraging and prove that, in principle, the technology works. As seen in figure 4, the contrast of coronary arteries can be increased on a “clean” heart with almost no epicardial fat. The ratio between the intensity of the red and infra-red signal values can be used as a criterion on whether or not to replace the original VIS-pixel by an enhanced version, and can be seen as a crude qualitative blood oxygenation related discriminator9. Arterial contrasts thus can be selectively enhanced without effecting already good venous contrasts in the visual range.

The figures 5 and 6 demonstrate that coronary vessels buried by epicardial fat can significantly be enhanced. This technique also holds potential for improved visualisation in cases of the intra-myocardial pathway of coronary arteries, epicardial adhesions after previous surgery and pericarditis. Exploration of these topics will be our next step after implementation of modifications which address the limitations of the present device, those being:

– sub-optimal image sharpness caused by motion, due to a limited frame-rate;

– limited focus depth range due to limited light source power;

– limited penetration depth within the tissue due to relatively simple optics for these first experiments.

Hardware and software solution strategies for these points already have been identified, and the implementation of these technological improvements is now in progress.

Conclusions

Our experiments resulted in improved visualisation of coronary vessels. Raw preview VIS & NIR image were real-time available, processed results were available within < 15 seconds. The method looks promising, but needs further development before it can be used as a real-time vision-enhancement device during cardiac surgery. Our planned improvements are designed to be obtained without sacrificing stereoscopic viewing, since it is clear that depth perception is crucial for surgical procedures1,3,5,6,11.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by TNO Quality of Life and by TNO O2 View BV (both based in Leiden, The Netherlands). Custom mechanical constructions were made by Mr. L. Bekkering and support on electronics was given by Mr. J. Honkoop (Biomedical Engineering Thorax Centre, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, The Netherlands). We greatly appreciated the possibility of filming during cardiac surgery. We therefore thank the surgeons involved, Dr. A.B.M. Maat and Dr. J. Kluin, as well as the OR-staff that supported the work (especially Dr. A. van der Woerd for photography) and the Department of Experimental Cardiology that facilitated filming in the animal lab OR (all within Erasmus MC Rotterdam, The Netherlands).