Although long term follow-up after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation shows a sustained clinical benefit in several randomized trials, delayed neointimal growth beyond the first 6 to 9 months has been reported in serial intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) analyses in some trials. The issue of a delayed restenosis which was observed after brachytherapy has not been thoroughly evaluated with DES.

Tissue growth inside the stent (Neointima)

Drug-eluting stents (DES) dramatically reduce neointimal growth at 6 or 9 months compared to bare metal stents (BMS).1-3 Although long term follow-up after DES implantation shows a sustained clinical benefit in several randomised trials,4,5 little is known about neointimal growth beyond the first 6 to 9 months. The issue of a “late catch up phenomenon” (delayed restenosis) which was observed after brachytherapy has not been fully investigated with DES.6

In porcine models, the inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia after deployment of polymer-coated sirolimus-eluting stents was not sustained at 90 and 180 days due to delayed cellular proliferation, and neointimal suppression after deployment of chondroitin sulfate and gelatin coated paclitaxel-eluting stents was also not maintained at 90 days.7,8

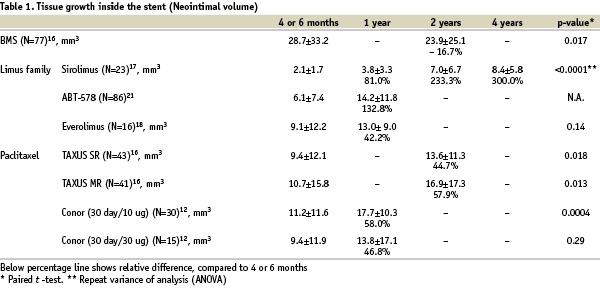

In humans, neointimal tissue does not keep growing after BMS implantation. During long-term angiographic follow-up, compaction of neointima has been described in several reports.9-11 Histological analyses of post-mortem coronary arteries demonstrate that compaction of neointima occurs due to the replacement of water-trapping proteoglycans by decorin and type I collagen.11 Following DES implantation, neointima continues to grow during the follow-up period in some trials in which serial IVUS analyses were performed (Table 1).

A chronic arterial response towards the durable polymer and to the remaining drug within the polymer has been imputed to explain this phenomenon. However, this was also observed with Conor paclitaxel-eluting stents in which neither polymer nor drug is retained at the end of the programmed release period.12 The precise reason for this observation is thus still unclear, but may be related to the delayed healing response and persistent biological reaction caused by the drug soon after the implantation of DES. In view of the results of animal studies and clinical studies, DES may delay restenosis, instead of halting definitively the process of neointimal hyperplasia. Further follow-up is warranted to evaluate the long-term efficacy of DES.

Tissue growth outside the stent (Vessel remodeling)

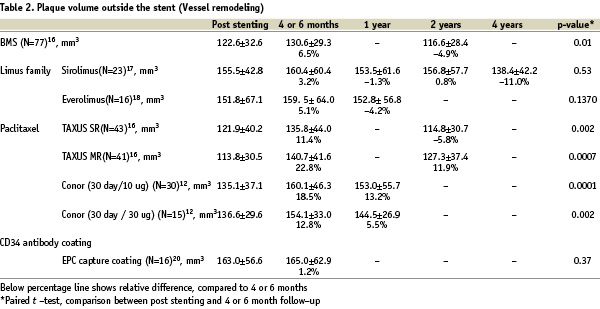

Polymer based sirolimus-eluting stents (Cypher) and polymer based paclitaxel-eluting stents (Taxus) are used in daily practice, and several types of drugs and durable or erodable polymers have been tested in clinical trials.1,3,13,14 After BMS implantation, expansive vessel remodeling (i.e. increasing plaque outside the stent) was reported.15 In the TAXUS II trial, the increased plaque outside the stent 6 months after BMS implantation had regressed completely at 2 years (Table 2).16

Thus, it is likely that mechanical injury and biological reaction against the stainless steel stent that may have induced the inflammation, had subsided by 2 years. After sirolimus and everolimus-eluting stents implantation, increasing plaque area outside the stent was insignificant in both the First In Man (sirolimus)17 and SPIRIT FIRST (everolimus) trials18, whereas a significantly increasing plaque area behind the stent was observed with paclitaxel-eluting stents in the TAXUS II15 and PISCES trials19, and tissue growth exceeded the vessel reaction observed with BMS in both trials. The EPC capture stents induce the rapid establishment of a functional endothelial layer early in the healing response and the mean plaque volume outside the stent was similar immediately post procedure and at 6-month follow-up, demonstrating that overall expansive remodeling did not occur with this device.20

The vessel reaction outside the stent differs from the reaction observed inside the stent, and the different drugs, polymers, and pharmacokinetics result in various effects on tissue growth not only in the intrastent neointima but also on vessel remodeling outside the stent. Interestingly, the timing of regression of the plaque outside the stent was also different. For sirolimus-eluting stents, significant expansive plaque outside the stent was not observed during follow-up and shrinkage of plaque outside the stent occurred at 4 years.17 For paclitaxel-eluting stents, complete regression of expansive plaque outside the stent was observed at 2 years in the slow release group in TAXUS II trial, and partial regression was observed at 1 year in the PISCES and at 2 years in the moderate release group in the TAXUS II trial.12,16 The exact reason for these variant vascular responses is unknown. The tissue growth outside the stent may be more complex and heterogeneous, compared to tissue growth inside the stent. The tissue growth inside the stent consists of smooth muscle cell and a proteoglycan rich matrix, whereas the tissue growth outside the stent consists of several components; 1) cell proliferations and intracellular matrix, 2) oedema caused by mechanical injury and chemical injury due to drug, polymer and stent, 3) growth or regression of existing atherosclerotic plaque. Studies involving larger sample sizes and more detailed analyses with novel in vivo techniques of tissue characterisation may be necessary to assess and better understand the process of vessel remodeling after DES implantation.