Abstract

Objective: To compare the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) in patients with multiple vessel coronary artery disease treated with drug eluted stents (DES), bare metal stents, percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) or bypass surgery (CABG).

Methods: In the Argentine Randomized Study Coronary Angioplasty versus Coronary Bypass Surgery in Multiple Vessel Disease (ERACI) III trial, 225 patients with multivessel disease who received DES met clinical and angiographic inclusion criteria for the ERACI II trial. This cohort (ERACI III-DES) was compared to both ERACI II treatment arms (ERACII-PCI and ERACI II-CABG). The primary end point was freedom from MACCE at one year.

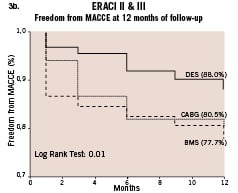

Results: Comparison of baseline demographic and angiographic data, revealed that ERACI III-DES patients were older, smoked more, had more diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, type C lesions and received more stents. At one year freedom from MACCE was significantly greater in ERACI III-DES cohort (88%) than ERACI II CABG (80.5% p=0.038) and ERACI II PCI (78% p=0.006) patients. The ERACI III-DES cohort had similar freedom from death and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) to ERACI II PCI patients but greater than ERACI II-CABG arm. Freedom from repeat revascularization was similar between ERACI III-DES to ERACI II-CABG (95.1% p=ns) patients, but both were significantly better than those in the ERACI II-PCI arm ( 91.2% and 83%p=0.002 and 0.02 respectively).

Conclusion: Patients with multiple vessel disease treated with DES in ERACI III had better one year outcomes than those treated with PCI or CABG in ERACI II.

Introduction

Several randomized studies have compared coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) to percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with balloon angioplasty (POBA) and/or bare metal stent placements1-13.

These studies showed similar incidence of death, myocardial infarction and stroke between both revascularization techniques in the mid- and long- term follow-up outcome. However, repeat revascularization procedures were significantly higher among patients undergoing PCI.10-14 Furthermore, two of the studies showed a trend towards high mortality rate in diabetics compared to non diabetics when they were treated with PCI techniques15-17.

With the advent of drug eluting stents (DES) several randomized and controlled studies have shown a significant reduction of clinical and angiographic parameters of restenosis. Indeed, paclitaxel (PES) and sirolimus (SES) eluting stents18-24 demonstrated a sustained benefit in both the diabetic and non-diabetic population when compared with bare metal stent therapy.

The purpose of the present study (ERACI III) was to compare short, medium and long term outcome of patients with multiple vessel coronary artery disease treated with DES and those treated with PCI or CABG in the earlier ERACI II trial11.

Methods

ERACI III is a multicentre, prospective, non-randomized and open labeled study designed to evaluate the role of SES and PES use in patients with multiple vessel disease who meet angiographic and clinical criteria of the earlier ERACI II trial11.

In order to obtain a comparable population and an equivalent revascularization strategy to that employed in ERACI II the same centres and investigators took part in the ERACI III trial.

Patient selection

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committees and all patients gave written informed consent. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had severely limiting stable angina (Canadian Cardiovascular Society class III-IV) despite maximal medical therapy and/or unstable angina, which included post myocardial infarction (AMI) angina.

Patients with no angina or minimal symptoms, but with a large area of “at risk” myocardium identified by exercise testing (two or more areas with perfusion defects) were also eligible. Unstable angina was defined according to Braunwald’s criteria25. Patients were required to have angiographic evidence of severe coronary obstruction (stenosis greater than or equal to 70% by visual estimation) in at least one major epicardial vessel and one significant lesion (greater than 50%) in other vessel. Only epicardial vessels with a reference size by visual estimation >2.5 mm were included. All lesions included in the analysis were considered amenable to both PCI and CABG revascularization based on angiographic assessment. The revascularization strategy was planned prior to the procedure and the aim was to achieve complete revascularization. The lesion considered culprit was treated first and then followed by PCI of the other vessels. This main vessel was always treated with at least one DES, SES or PES. Treatment at least with one DES design was an inclusion criteria of the study. SES was used in 52% of the patients and PES in the other 48%. Placement of a bare metal stent design in the main vessel was not allowed. Lesion length greater than 20mm was not criteria for exclusion of the study. Revascularization was considered complete when all severe stenoses (>70%) were treated successfully with stents. Chronic totally occluded vessels supplying akinetic left ventricular segments, were usually not attempted26.

Patients with unprotected left main stenosis could be also included if they were considered amenable to percutaneous treatment by the interventionalist.

Treatment of lesions of 50% to 70% severity was at the discretion of the physician.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had single vessel disease, prior CABG, PCI in the preceding year, in-stent restenosis, acute myocardial infarction in the last 48 hours, poor left ventricular function (an ejection fraction of less than 35%), two or more chronic total occlusions, severe concomitant valvular or myocardial heart disease, limited life expectancy, history of cerebrovascular accident, neutropenia or thrombocytopenia, aspirin or thienopyridines intolerance, a requirement for concomitant vascular or general surgery or if they were deemed unsuitable for long term antiplatelet therapy or not amenable to treatment with DES therapy.

Medication

Prior to PCI all patients in ERACI III received an oral loading doses of 300mg of clopidogrel plus 325mg of aspirin. Administration of a glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor during PCI was strongly recommended in patients with unstable angina class III or C and in diabetics. All lesions were pretreated with balloon angioplasty before stent placement. Stents were deployed at 13 to 14 atmospheres. The nominal DES diameter was 2.5 mm to 3.5 mm and length 16 mm to 33 mm.

After PCI, all ERACI III patients received clopidogrel 75 mg daily doses, three and six months with SES and PES respectively. Aspirin was given indefinitely. Lipid lowering agents were prescribed in all ERACI III patients post PCI procedure, irrespective of cholesterol levels.

In ERACI II patients received lipid lowering agents depending on baseline cholesterol levels and thienopyridines (Ticlopidine) were given for one month.

Study end points

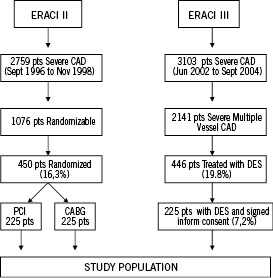

The primary end point of the study was freedom from major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) defined as death by any cause, non-fatal myocardial infarction, major stroke and/or repeat revascularization procedures (PCI or CABG) at one year of follow-up . A comparison was made between ERACI III patients treated with DES therapy (ERACI III-DES) and previously reported ERACI II data - bare metal stent (ERACI II-PCI) or CABG (ERACI II-CABG) treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow charts from ERACI II and ERACI III.

Secondary end points of the study were to compare the incidence of MACCE between ERACI III-DES, ERACI II-PCI and ERACI II-CABG arms at 30 days, two, three and five years follow-up; the incidence of MACCE among diabetic patients within each of the three revascularization groups and cost effectiveness of the three revascularization strategies. Incidence of stent thrombosis in ERACI III during the five years of follow-up was also analysed as a secondary end point of the study.

End points definitions

Death included mortality from all causes. A Q-wave myocardial infarction was defined as new pathologic Q waves, or new left bundle branch block with more than a 3 fold rise of creatine-kinase, a MB fraction (CK-MB) rise and was judged on the basis of a review of all electrocardiogram obtained as part of the study protocol or others associated with admission.

Stent thrombosis (SET) was predefined27 as:

1. Suspected Stent Thrombosis. When the patient suffered unexpected cardiac or sudden death or had an ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) which correlated with the area of DES placement. Patients who had a non STEMI or whose electrocardiogram from the time of the acute event could not be reviewed, were not included in this category.

2. Confirmed Stent Thrombosis. When the patient had angiographically documented stent thrombosis with TIMI flow 0 or 1, or the presence of a flow-limiting thrombus (TIMI flow 1 or 2). Both SST and CST were counted as definitely SET.

All clinical events were adjudicated by Clinical Events and Safety Committee.

Statistical analysis

The sample size of the study was determined using a test for trend analysis based on an estimation of the incidence of the primary end point of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at one year of follow up among patients treated with DES compared with ERACI II stent arm. In line with recently published randomized data regarding DES treatment (SIRIUS, E-SIRIUS, C-SIRIUS, TAXUS II and TAXUS IV) and also based on our previous ERACI trial data1,11 (35% of MACCE reduction among ERACI II with bare metal stent versus ERACI I with balloon angioplasty), we predicted a 50% reduction of MACCE with DES therapy. Thus, based on the 22.3% incidence of MACCE at one year in the ERACI II-PCI arm11, we expected a one year incidence of MACCE of about 10 to 12% with DES1,11,18-23. Consistent with the above data, and using a two-sided test for differences in independent binomial proportions with an alpha level of 0.05, we calculated that approximately 210 patients treated with DES were required to guarantee a power of 80%.

Continuous variables were compared using ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Categorical variables were compared using chi square analysis or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD and categorical variables as percentages. Freedom from survival end points at follow-up were obtained using Kaplan Meier curves and compared by log rank test.

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed using SPSS v14.0 (intro mode: all variables introduced in block in a single step) to determine independent predictors of poor outcome at one year, thus correcting for demographic, clinical and angiographic confounders. Variables of statistical significance after univariate analysis and clinically relevant covariates were included in the analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant27.

Results

Between June, 2002 and September, 2004, 3,103 patients with coronary artery disease underwent coronary angioplasty and stenting in the centres participating in the ERACI III trial (see Appendix). Of these, 2,141 patients had multiple vessel disease and 225 (7.2%) who met the study inclusion criteria and signed the informed consent were consecutively included in the ERACI III study (Figure 1). All ERACI III patients underwent PCI and had at least one DES deployment. Of the ERACI III patients 52% received a SES and 48% a PES.

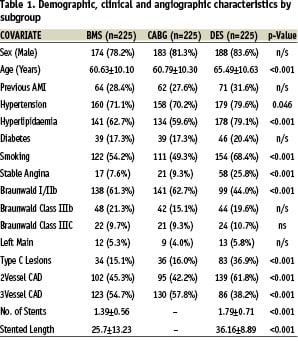

Baseline demographic, clinical and angiographic characteristics of the ERACI III patients are described in Table 1.

Analysis of baseline characteristics confirmed that ERACI III patients were significantly older and had a higher incidence of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and smoking than those included in ERACI II. ERACI III patients also had more complex (type C) lesions, more stents placed per patient and had greater vessel stented length. In contrast, ERACI II patients were more likely to have three vessels disease.

Complete anatomical revascularization was achieved in similar proportions ERACI III-DES and ERACI II-PCI patients (48% vs 50.2% respectively; p=ns), though significantly higher levels were achieved in the ERACI II-CABG arm (85%). However there was no significant difference in levels of complete functional revascularization attained (the PCI goal) between the groups (ERACI III-DES (88.4%), ERACI II-PCI (83.5%) and ERACI II-CABG (85%); p=n/s.

In-hospital and 30 days outcome

Procedural, clinical success and hospital MACCE in ERACI III was similar to that in the ERACI II-PCI arm and both were significantly lower than the ERACI II-CABG arm. GP IIb-IIIa inhibitors were used also in a similar proportion of patients in the PCI groups. There were no significant differences between the ERACI III-DES and ERACI II-PCI arms in terms of p value. Procedural and in-hospital adverse events (death 0.9% vs 0.9%; AMI 0.9% vs 0.9%; stroke 1.3% vs 0% respectively; p= n/s for all comparisons).

In-hospital emergency repeat revascularization due to stent thrombosis was required in one (0.4%) ERACI III-DES patient and three (1.3%) ERACI II-PCI patients (p=ns). However three additional ERACI III patients developed stent thrombosis three, five and seven days post hospital discharge. Two of them were confirmed by angiography.

At one month follow-up, the composite MACCE rate in the ERACI III-DES group (4.4%) was similar to the ERACI II-PCI arm (3.6%; p=n/s), but significantly lower than in the ERACI II-CABG (12.3%; p=0.002) arm. The latter reflects a high incidence of in-hospital death and acute myocardial infarction among ERACI II-CABG patients in that trial11.

One year follow-up

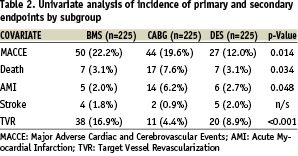

UNIVARIATE ANALYSIS

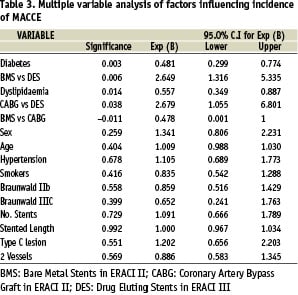

Univariate analysis of outcome by subgroup and multivariate analysis of factors influencing MACCE at one year are represented in tables 2 and 3 respectively.

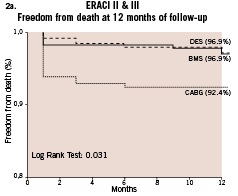

The incidence of MACCE, death, AMI and TVR but not stroke differed significantly between the 3 study groups when determined by univariate analysis (Table 2). One year incidence of MACCE was significantly lower in ERACI III (12%) compared to ERACI II-PCI arm (22.2%; p=0.0056) and ERACI II-CABG (19.6%; p=0.038). One year incidence of death, which included in-hospital outcome, was similar in the ERACI III-DES (3.1%) and ERACI II-PCI (3.1%) arms and hence had similar survival curves (96.9% in both groups) however death in ERACI II-CABG arm (7.6%) was significantly higher (survival 92.4% p=0.031 Figure 2-A). The one year incidence

of death plus myocardial infarction was 5.1% in ERACI II-PCI arm versus 5.8% in ERACI III-DES (p=ns). The corresponding freedom from death and AMI curve was 94.3% in ERACI III, 94.6% in the ERACI II-PCI arm (p=ns) and 86.2% in ERACI II-CABG arm (p=0.01 for both comparisons). (Figure 2-B)

Figure 2. a. Freedom from Survival among ERACI III, ERACI II-PCI and ERACI II-CABG; b. Freedom from death/AMI among ERACI III, ERACI II-PCI and ERACI II-CABG.

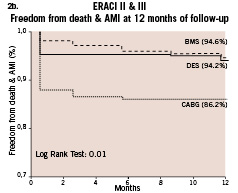

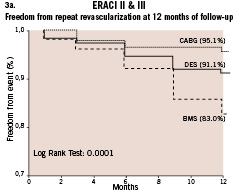

The incidence of repeat revascularization was significantly lower in ERACI III compared to ERACI II-PCI arm (8.8%vs 16.9% respectively p=0.016) and similar to the CABG arm of ERACI II (8.8%vs 4.9% respectively p= ns). The corresponding freedom curve from repeat revascularization procedures (Figure 3-A) was similar among ERACI II-CABG arm and ERACI III (94.7% and 91.2% respectively p=ns) and both significantly better than ERACI II-PCI arm (83% p<0.001 for both comparisons). The corresponding freedom from MACCE curve (Figure 3-B) showed a significant differences among ERACI III versus ERACI II-CABG and PCI arm (88% versus 80.5% and 77.7% respectively p=0.01). MACCE was 8.5% and 14.8% with PES and SES respectively (p=ns).

Figure 3. a. Freedom from repeat revascularization procedures between ERACI III, ERACI II-PCI and ERACI II-CABG; b. Freedom from MACCE between ERACI III, ERACI II-PCI and ERACI II-CABG.

Among ERACI III-DES patients the incidence of repeat revascularization was similar for PES and SES (6.3% vs 10.6% respectively; p=ns).

Three patients in ERACI III developed SET more than 30 days and less than 12 months post-procedure (49, 204 and 227 days). Thus overall SET was 2.6% in ERACI III. This is in contrast with the ERACI II-PCI arm where there were no reports of SET during the first year of follow-up11. Five of the patients with SET had discontinued clopidogrel therapy and three of the six suffered a cardiac death related to the acute thrombotic event. The incidence of SET was similar between PES and SES (three cases with each).

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed, correcting for demographic, clinical and angiographic confounders to determine independent predictors of poor outcome at one year. Significantly, MACCE at one year was higher among patients treated with CABG compared to DES (p=0.038) and those treated with BMS compared to DES (p=0.006), and was similar between CABG and BMS (p=n/s) (Table 3). Differences in the incidence of death and AMI, when considered individually after correction for confounders, failed to reveal a significant difference between treatment arms. A trend towards increased stroke was seen in both the DES and BMS groups when compared to CABG (p=0.054 and p=0.071 respectively). The incidence of TVR at one year was significantly higher among those treated with BMS compared to both DES (p=0.002) and CABG (p=0.02), but not significantly different between the latter two groups.

Along with treatment subgroup both hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus were significant independent predictors of MACCE in the multivariate model (p=0.014 and 0.003 respectively) (Table 3).

Diabetic versus non-diabetic patients

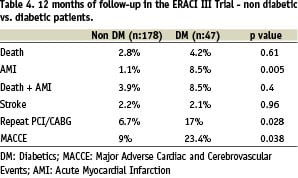

Of the patients in ERACI III 21% had a diagnosis of diabetes (DM). When all 3 treatment arms were combined, univariate analysis revealed that patients with diabetes (n=124) had a significantly higher incidence of MACCE at one year when compared to non-diabetics (n=551) (27.4% vs 15.8% p=0.004). An association between DM and TVR appeared to be the main determinant of MACCE (18.5% DM vs 8.3% non DM; p=0.002) .

Furthermore, patients with DM in ERACI III-DES had poor outcome when they were treated with PCI: MACCE 9% in DM, vs 23.4% in non DM p=0.038. (Table 4)

Comparison of DM patients treated with DES in ERACI III and DM from the ERACI II-PCI arm failed to demonstrate a significant improvement in death and myocardial infarction (8.5% vs 10.2% respectively), repeat revascularization (17% vs 28% respectively) or MACCE (23.4% vs 36.3% respectively).

Discussion

Percutaneous DES therapy has brought about a significant reduction in clinical and angiographic parameters of coronary restenosis. Several randomized controlled studies have demonstrated a significantly lower rate of angiographic restenosis, target vessel revascularization (TVR) and MACCE with both SES and PES when compared to BMS17-23. The principle aim of ERACI III, a prospective, multicentre study, was to compare the incidence of MACCE among patients with multivessel CAD treated with DES to BMS and CABG-treated patients from the earlier ERACI II study.

ERACI III patients treated with DES for multivessel CAD had a significantly lower incidence of MACCE at 1 year when compared to patients treated with BMS and a similar incidence of those in the CABG arm of the earlier ERACI II study. The need for repeat revascularization after treatment with DES was significantly lower than with BMS therapy and comparable to that of CABG. In addition, analysis of the diabetic population combined from the three revascularization strategies demonstrated a significantly increased incidence of MACCE when compared to the non-diabetic patients. The need for target vessel revascularization appeared to be a major contributor to this composite endpoint.

In ERACI III, repeat revascularization was required in 8.8% of DES patients and 17% in ERACI II-PCI patients, p=0.002. This represents a 48% relative risk reduction (RRR) of TVR at one year with DES therapy. Incidence of MACCE was 12% and 22.2% for ERACI III-DES and the ERACI II-PCI arms respectively (p=0.002), which represents a 34% RRR. Indeed these results are comparable with POBA and bare metal stent analyses from previous ERACI trials1-11. Incidence of death or death plus myocardial infarction however did not differ significantly between PCI strategies (BMS and DES). However, ERACI III patients showed freedom from repeat revascularization (Figure 3-A) and MACCE (Figure 3-B) comparable to that of surgical patients.

Since the first randomized comparison between PCI techniques and CABG was performed, several randomized and observational trials have shown poor outcome in diabetics patients treated either with balloon angioplasty or bare metal stent4,6,7,10. Consistent with this the ERACI II trial showed a significant lower freedom from MACCE in PCI treated patients relative to CABG patients at five year of follow-up15. Furthermore BARI, EAST and ARTS also showed that diabetes was an independent predictor of increased mortality in PCI treated patients4,6,7,10.

In ERACI III, despite the use of DES, incidence of TVR and MACCE was worse for diabetics patients compared to non-diabetics (Table 4).

The recently published ARTS 2 trial in which SES were deployed reported one year follow-up results in both diabetic and non diabetic patients28. Incidence of repeat revascularization procedures and MACCE in that study were similar to those in ERACI III (8,5% and 10.5 in ARTS 2 vs 8.8% and 12% respectively in ERACI III ) and also both studies showed similar relative reduction of MACCE and TVR when compared with previous bare metal stent randomized trials13,14. Analysis at longer term follow-up is required however to establish if DES improves outcome in this high risk cohort of patients.

The issue of stent thrombosis with DES is a contentious one. In the PCI arm of ERACI II, 1.3% of patients developed acute stent thrombosis. The incidence in ERACI III (0.4%) appears to compare favorably, though out of the hospital shows a reversal in this trend. There were no reported cases of stent thrombosis post discharge in the ERACI II-PCI arm, whereas six patients had acute stent thrombosis at one year of follow-up in ERACI III26. The ARTS 2 study did not report an excess of SET with SES28. Differences in antiplatelet therapy compliance and SET definitions (a secondary end point of our study) between the trials might explain these discrepancy. Late stent thrombosis is usually a severe but rare event with bare metal stent design. However, the incidence associated with DES will require a considerably larger study26,29. Indeed the overall incidence of adverse cardiac adverse events was lowest in the DES group in our study.

Finally, despite recent randomized data indicating better outcome with SES compared with PES, our trial has not shown any significant difference in outcomes between the two groups at one year30,31.

In conclusion, this multicentre, prospective and controlled study in patients with multivessel disease treated either with SES or PES stents, demonstrated a significant reduction of MACCE and the need for repeat revascularization when compared to our previous PCI bare metal stent data from ERACI II. Further analyses are required to establish if there is a significant improvement in outcome among diabetic patients.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is a non-randomized study, and its well known that randomized comparison are the most appropriate study design to evaluate medical or surgical procedures in clinical practice, however, well designed, and controlled registries have also proven useful in evaluating revascularization techniques32.

Secondly, the study was not performed with contemporary percutaneous coronary interventional equipment and techniques. Specifically improved PCI material, lower balloon profile, more deliverable guide wires, adjunctive glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors and better secondary prevention practices, such as routinely prescription of lipid lowering agents in all DES patients and more aggressive and prolonged antiplatelet therapy, etc. may have contributed to a beneficial effect in our ERACI III-DES study arm.

Thirdly, the high in-hospital rate of MACCE reported in the ERACI II-CABG arm may artificially inflate the relative benefit of DES use at one year11.

Finally, we are presenting the one year follow-up data, and do not know if the DES efficacy and safety findings will be sustained over a longer follow up period. Randomized controlled trials comparing DES with CABG, in patients with multivessel disease, such as the FREEDOM trial in diabetics and the SYNTAX trial in patients with three vessel disease and left main coronary artery disease are ongoing and will further elucidate the relative benefit of these techniques.

Appendix

The following are participants in ERACI III trial:

Steering Committee: Alfredo E. Rodriguez, Liliana Grinfeld, Daniel Berrocal, Igor Palacios, William O Neill.

Safety and Ethics Committee: Alberto Lambierto, Jorge Pascual, Gustavo Poggi, Julio Baldi.

Clinical Events Committee: Miguel Russo Felsen, Valeria Curotto, Fernando Guerrico

Coordinating Center and Statistics: CECI (Centro de Estudios en Cardiologia Intervencionista) Alfredo Rodriguez, Andrew O Maree, Carlos Fernandez Pereira, Alfredo M. Rodriguez-Granillo

Participating Hospitals and Clinical Investigators: (numbers in parenthesis are the numbers of patients randomized) Otamendi Hospital, Buenos Aires (138) Alfredo E. Rodriguez, Carlos Fernandez-Pereira, Cesar F. Vigo, Sanatorio Las Lomas, San Isidro, Buenos Aires (17) Alfredo E. Rodriguez, Maximo Rodriguez-Alemparte, Juan Mieres, Clinica IMA, Adrogue, Buenos Aires (13) Carlos Fernandez-Pereira, Carlos Mauvecin, Hospital Italiano, Buenos Aires (31) Liliana Grinfeld, Daniel Berrocal, Jorge Gabay, Hospital Español, La Plata, Buenos Aires (26) Liliana Grinfeld, Diego Grinfeld.