Abstract

Aims: Performing simultaneous renal angiography in patients undergoing coronary angiography for suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) is suitable for those who have a high probability for renal artery stenosis (RAS), thus better recognition of all potential candidates could have paramount importance.

Methods and results: In a cross sectional study, 260 consecutive hypertensive and/or diabetic patients (135 males, 125 females with average age of 57.1 and 57.2 years respectively) underwent simultaneous coronary and renal angiography. RAS was identified in 55 patients (21.2%). Significant RAS (> 50%) was present in 37 patients (14.2%). Female sex (P=0.01), older age (62.1±10 vs 56.3±8.9 years, p=0.001), higher serum creatinine level (1.3±0.69 vs 0.98±0.35 mg/dl p=0.017), reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (58.6±25.4 vs 81.8±28.1 ml/min/1.73 m2, p< 0.001), increased levels of intra-arterial systolic blood pressure (169.8±31.1 vs 155.1±28.4 mmHg, p=0.004) and pulse pressure (90.9±26.2 vs 77.5±21.9, p=<0.001) during catheterisation, history of hypertension alone (p=0.007) or accompanied with diabetes mellitus (DM) (p=0.014) and multi vessel CAD (> 2 vessels, p=0.002) were associated with significant RAS in univariate analysis and normal coronary arteries was a strong negative predictive factor (negative predictive value=95%). There was no significant relationship between involved location of coronary arteries, history of DM alone, history of dyslipidaemia and smoking with RAS. In multivariate model, female sex [odds ratio (OR) 0.3; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.12-0.80, P=0.016], multivessel CAD (OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.25-2.83, P=0.002) and reduced eGFR (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.95-0.99, P=0.002) were independent predictors of RAS.

Conclusions: Considering the limitations of non-invasive techniques, it seems worthwhile from both diagnostic and prognostic standpoints to perform simultaneous renal angiography following coronary angiography in patients with multivessel CAD, especially if other mentioned risk predictors are also present.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (RAS) is an important and often overlooked contributor to renal insufficiency, refractory hypertension (HTN) and overall cardiovascular mortality. It is also a part of a diffuse process of atherosclerosis which is unfavourably associated with poor prognosis1-15.

Although RAS accounts for less than 3% of end stage renal disease (ESRD)1, it represents a potentially treatable condition with surgical or percutaneous revascularisation which is associated with improved clinical outcomes including: the reduction in the number of antihypertensive medications, improved control of HTN and, more importantly, preservation of renal function and prevention of haemodialysis with timely intervention1-3,5,7-9.

Currently, there is no specific, simple guideline for performing simultaneous renal angiography13 following coronary angiography and because no other screening study can reasonably exclude the presence of disease1,8, better recognition of all potential candidates has paramount importance.

In many other studies demographic variables, atherosclerotic risk factors, presence of atherosclerosis in other vascular beds, impaired renal function and extent and severity of coronary artery disease (CAD) has been mentioned as predictors of RAS, but there is considerable variability among results of these studies, including independent predictors of RAS1-14.

Our purpose was the evaluation of these risk predictors and prevalence of RAS in our patients. Since diabetic patients have a greater atherosclerotic burden and accelerated atherogenesis and HTN is more common and tends to be more persistent in these individuals1 we considered diabetic patients as a separate group in our study.

Patients and methods

In a cross-sectional study of patients who were candidates for evaluation of suspected CAD, a total of 260 were enrolled in two educational hospitals in Mashhad (Emam Reza & Qaem) from April 2005 to 2006.

Selection criteria included hypertensive or diabetic subjects, and patients were excluded if serum creatinine level was > 2.5 mg/dl. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and informed consent was obtained from all patients. At the beginning, demographic variables, laboratory data and atherosclerotic risk factors were recorded.

Patients were considered to have a history of HTN according to the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC-7) criteria. Patients were considered diabetic according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria (1997). A history of dyslipidaemia (DLP) was established according to primary prevention goals from the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult treatment panel III). In addition, all patients who were under treatment for HTN, DM or DLP were included into the study.

The patients were considered smokers if they were current smokers or had quit smoking less than two years before. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from the plasma creatinine concentration, age and gender and by the four variable modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation, which is the superior method because it does not rely on body weight1 and is expressed as millilitre per minute per 1.73 m2 body surface area (ml/min/1.73 m2).

All patients underwent simultaneous renal angiography following elective coronary angiography with either selective method using a right Judkins catheter and 15 percent straight contralateral projections with hand injection, or abdominal aortography using a pigtail catheter and anteroposterior view with a pump injector at a rate of 15 ml/sec. About 20-30 ml additional contrast material were used by both techniques. No patient suffered early complications including neither contrast induced nephropathy nor dissections.

Significant CAD was considered if coronary artery narrowing > 50 percent was present. RAS with a stenosis diameter > 50 percent was considered significant.

All angiograms were recorded digitally at a speed of 25 frames/sec and interpreted as a consensus of two cardiologists by visual estimation.

Statistical analysis

After completion of data collection, all data was encoded and statistically analysed using SPSS software version 13.0 for windows (SPSS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The relationship between RAS and other variables was examined using student’s t-test for normal continuous variables and chi-square test for discontinuous ones. Numerical variables were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) and categorised variables as percentages. Finally, by multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis, independent predictors of RAS were determined and expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

P values of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of our patients, 51.9% were males with an average age of 57.1 ±10.7 years and 48.1% were females with an average age of 57.2±9.4 years showing a balanced distribution of participants.

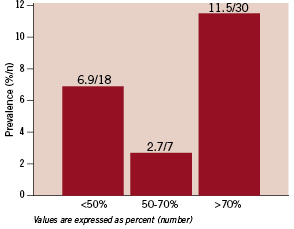

As for atherosclerotic risk factors, 175 patients (67.3%) had HTN, 88 patients (33.8%) had DM, 165 patients (63.5%) had DLP and 39 (15%) were smokers. Overall prevalence of RAS was 21.1% (55 patients). Significant RAS was present in 37 patients (14.2%) which was mainly high grade (>70 percent) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overall prevalence of RAS was 21.1%, predominately high grade (>70%).

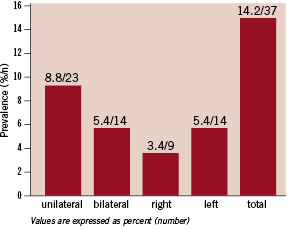

In 23 (8.8%) of these patients with significant disease, RAS was unilateral (on the left side in 14 patients and on the right in nine) and in 14 subjects (5.4%) it was bilateral (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Prevalence of significant RAS was 14.2% (8.8% unilateral, 5.4% bilateral, 5.4% on left side and 3.4% on right side).

Patients with high grade stenoses were referred directly for angioplasty and those with 50-70% stenoses underwent captopril renal scanning to determine haemodynamically significant lesions which required intervention.

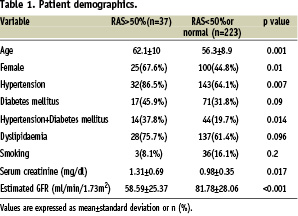

There was a significant relationship between RAS and the hypertensive only group (P=0.007) and patients who were both hypertensive and diabetic (P=0.014). The diabetic only group did not show any significant relationship with RAS (P=0.09).

The average age of patients with significant RAS was 62.1± 10 years vs 56.3±8.9 years in those without significant RAS (P=0.001) and prevalence of significant RAS was higher in females (P=0.01). There was no association between RAS, DLP (P=0.096) or smoking (P=0.2).

Average serum creatinine and eGFR levels in patients with significant RAS was 1.3±0.69 mg/dl and 58.6±25.4 ml/min/1.73 m2 vs 0.98±0.35 mg/dl and 81.8±28.1 ml/min/1.73 m2 in patients without significant RAS with p values of 0/017 and <0.001 respectively (see Table 1 for baseline characteristics).

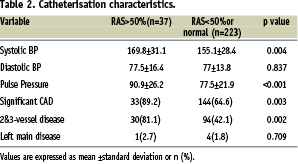

Average intra-arterial systolic, diastolic and pulse pressures during catheterisation were 169.8±31.1 vs 155.1±28.4 mmHg for systolic BP, 77.5±16.4 vs 77±13.8 mmHg for diastolic BP and 90.9±26.2 vs 77.5±21.9 for pulse pressure in patients with vs without significant RAS.

There was a good relationship between systolic and pulse pressures (p values of 0/004 and <0.001 respectively), but not diastolic blood pressure (P=0/837) and RAS (Table 2 for catheterisation characteristics).

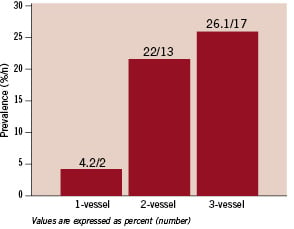

In 177 patients with CAD, significant RAS was more common (18.6%, P=0.003) and in 83 individuals (31.9%) with normal coronary arteries, only five had RAS in which four were significant (6% and 4.8% with negative predictive values of 84% and 95% respectively). Significant RAS was present in 4.2% of patients with one vessel disease, 22% of those with two vessel disease and 26.1% of patients with three vessel disease (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Prevalence of significant RAS by the number of diseased coronary arteries.

Following this it seems that patients with significant RAS were more likely to have multivessel CAD (P=0.002), but there was no significant relationship between involved location of coronary arteries (proximal, mid or distal portions) and RAS (P values >0.1).

Interestingly, with increasing numbers of proximally involved coronary arteries prevalence of significant RAS increases (P<0.001), but this was not true for mid or distal portions (p=0.45).

Finally, by multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis female sex (OR 0.3; 95% CI 0.12-0.80, P=0.016), multivessel CAD (OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.25-2.83, P=0.002) and reduced eGFR (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.95-0.99, P=0.002) were independent predictors of RAS.

Interestingly, after excluding the diabetic patients from analysis for elimination of possible effects of occult diabetic nephropathy on eGFR, eGFR was no longer seen as an independent predictor.

Discussion

The overall prevalence of RAS in our patients was considerably high and unilateral involvement predominated (left more than right side).

The presence of significant RAS in 14.2% of our study population is within the previously reported range of prevalence in patients undergoing coronary angiography, and its predominant unilateral affliction is in agreement with most other studies.

It seems that HTN is both an important risk factor and a manifestation of RAS, and DM alone is not a significant predictor of RAS unless HTN coincides with it. Multivessel CAD is an independent predictor of RAS irrespective of its involved locations (proximal, mid or distal portions) and normal coronary arteries are a strong negative predictor. As far as we know, our study is the first study which addressed the relationship between RAS, and distribution of coronary artery lesions. The independent predictive value of multivessel CAD for RAS prediction is in agreement with most other studies. Having eGFR below 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 is an important known breaking point for adverse cardiovascular outcomes1 and in our study this was reconfirmed for RAS prediction, thus, it is prudent to calculate eGFR before catheterisation, not only for diagnostic purposes, but also for other reasons such as: long-term cardio-renal protection with appropriate medical treatment and timely use of preventive strategies for contrast induced nephropathy (CIN). It is worth noting that in our study, after exclusion of the diabetic patients, eGFR was no longer seen as an independent predictor of RAS, possibly because of decreased eGFR due to occult diabetic nephropathy. To the extent of our knowledge, this issue has not been addressed before in the literature.

This study presents new insight concerning the relationship between atherosclerotic involvement in different locations (proximal, mid or distal portions of coronary arteries) and different vascular beds (renal and coronary arteries) which needs to be more extensively studied in larger series. Although our study shows that the number of diseased coronary arteries is far more important than involved locations, the hypothesis that atherosclerotic RAS affects predominantly the proximal portions of renal arteries and its association with CAD is predominantly in proximal disease and should be taken into account and evaluated in future studies.

Conclusion

Considering the limitations of non-invasive techniques, it seems reasonable, safe and cost effective to perform renal as well as coronary angiography in patients with multivessel CAD, especially if other risk predictors including HTN alone or accompanied with DM, elevated intra-arterial systolic and pulse pressures during catheterisation, advanced age, female sex and reduced eGFR are also present.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate Dr. Ramin Sadeghi’s assistance in revising this paper.