“If you always do what you always did, you will always get what you always got.”

Albert Einstein

The choice of endpoint is an important decision in the design of clinical trials. This choice has been compounded by the rapid expansion in the spectrum of endpoints, particularly in cardiovascular clinical trials. Hence, in lieu of a single event there are now multiple types of event often combined to form a single outcome as a composite endpoint. The first mega trial in acute myocardial infarction, Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue plasminogen activator for Occluded coronary arteries (GUSTO-I), was designed on the primary endpoint of 30-day death1. In contrast, most contemporary trials are based on a composite endpoint of at least two and often four or more event types. This transformation has been precipitated by both wanting to reflect the patient experience and decreasing rates for single events, such as mortality, thereby impacting on the projected sample size needs, and, pari passu, challenging the operation and financing of such trials. Combining multiple types of clinically relevant events into a single endpoint is one strategy to buffer this new reality. However, as each of these individual rates declines, this has led to the inclusion of increasingly disparate composites, encompassing death and recurrent ischaemia, for example, as an equivalent outcome. It may also be argued that patient-oriented outcomes have long been absent from the evaluation of new treatments.

Despite this evolution in the choice(s) of endpoint, the approach to their analysis has not kept pace. Traditional analysis of endpoints, both single and composite, is time-to-first-event. However, this approach does not take into account multiple events in a single patient, their differential clinical impact, sequencing and time course, thereby potentially wasting valuable and clinically meaningful data. Additionally, this approach biases the analysis towards using the earlier and potentially less severe events. There are also important assumptions underlying the use and analysis of composite endpoints, which are infrequently satisfied (Table 1).

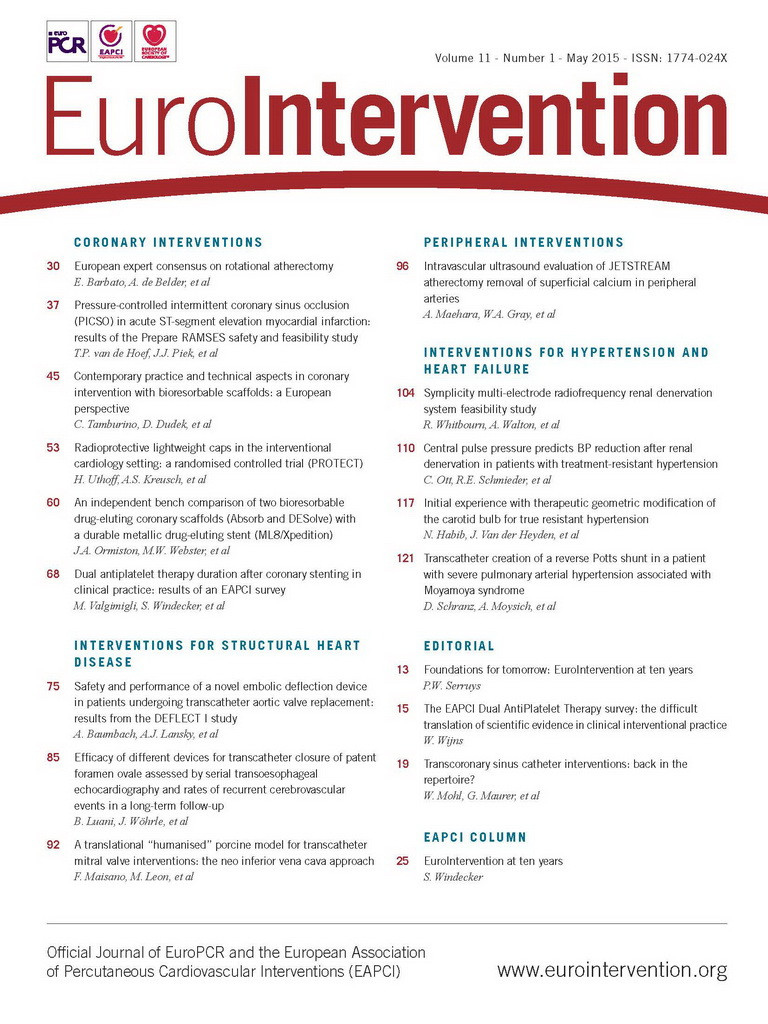

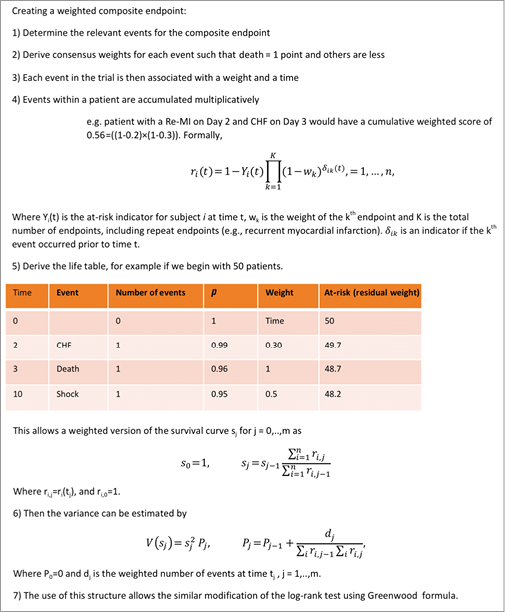

Alternative methodologies were developed in the late 1980s and 1990s to handle multiple occurrences of the same event2-4. These were intended for the analysis of multiple events of the same type more often seen in areas such as oncology (e.g., recurrence of tumours) rather than multiple events of different types typical of cardiology trials. While these approaches deal with the multiplicity of events, the relative value of event types is not accounted for (i.e., all events are valued equally). There is recent and increasing discomfort with this status quo, and new methods are emerging in cardiovascular research5-7. One such approach is the weighted composite endpoint (Figure 1)8-12. In this approach, the relative severity weights for each component of the composite endpoint are first determined based on a survey of stakeholders. In our previous work, the stakeholders were experienced clinician-investigators; however, more recent efforts have sought the perspective of patients12. The results based on a contemporary ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) trial generated the following weights: death (1.0), cardiogenic shock (0.5), congestive heart failure (0.3), and reinfarction (0.2)8. Patients with multiple events were treated multiplicatively. Using this approach, each patient has a residual weight on each day; if a patient had no events, their weight was 1.0; if events occurred, their score was reduced according to the type and number of events, thereby providing a real-time weighted event rate. For example, a patient with cardiogenic shock on day 1 would have a residual weight of 0.5 at the end of day 1 (1-0.5=0.5) (Figure 2A). If a reinfarction then occurred on day 3, the residual score would be reduced to 0.1 (0.5*0.2=0.1). In Figure 2B, a patient experienced reinfarction on day 2 and then death on day 3 of follow-up. Note that the occurrence of death fully eliminates any residual weight. Based on this weighted event rate, the association between the study treatment and the composite endpoint would be analysed with a modified Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and modified log-rank score as the test between treatment groups.

Figure 1. Creating a weighted composite endpoint.

Figure 2. Illustration of residual weights at the end of each day of follow-up in a sample patient with cardiogenic shock on day 1 and reinfarction on day 3 (A), and in another patient with reinfarction on day 2 and death on day 3 (B).

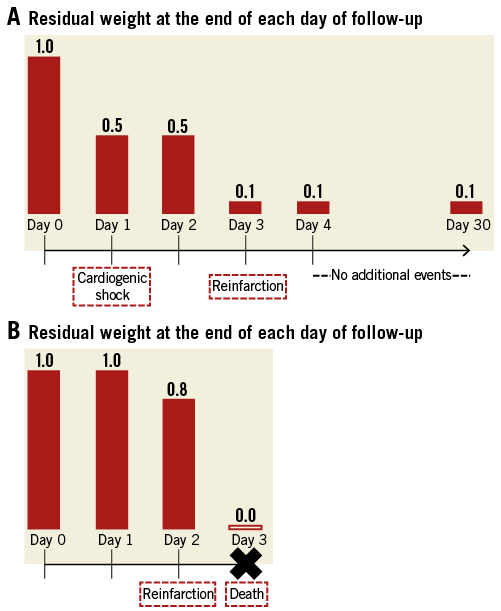

A post hoc application of the weighted composite analysis of the Trial of Routine Angioplasty and Stenting after Fibrinolysis to Enhance Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (TRANSFER-AMI) trial, comparing early PCI to standard treatment of STEMI, revealed two important observations which may not be uncommon in the traditional time-to-first-event analysis10. Recall that one assumption of the traditional composite endpoint is that the direction of association of treatment with all components of the composite should be the same. This assumption, however, was violated in the TRANSFER-AMI trial as the direction of death and cardiogenic shock was opposed to that of reinfarction and recurrent ischaemia; secondly, recurrent ischaemia clearly drove the benefit for early PCI. However, this event should or could be considered the least clinically relevant among the other components in the composite endpoint. Introducing the relative weights of the events calibrated the analysis such that no significant difference between the treatment groups was observed, unlike the standard time-to-first-event analysis (Figure 3)13.

Figure 3. Analysis of patients enrolled in the TRANSFER-AMI trial. Left panel: traditional time-to-first-event (30-day death [1.0], cardiogenic shock [1.0], congestive heart failure [1.0], reinfarction [1.0], and recurrent ischaemia [1.0]) comparing early PCI (blue: - line: Kaplan-Meier estimate; shaded area: 95% confidence region) to standard treatment (red: - line: Kaplan-Meier estimate; shaded area: 95% confidence region). Right panel: weighted composite endpoint (30-day death [1.0], cardiogenic shock [0.5], congestive heart failure [0.3], reinfarction [0.2], and recurrent ischaemia [0.1]) comparing early PCI (blue: - line: Kaplan-Meier estimate; shaded area: 95% confidence region) to standard treatment (red: - line: Kaplan-Meier estimate; shaded area: 95% confidence region).

Another advantage of the weighted composite endpoint approach is the full use of the data collected, as all events, not only the first, are counted. This enhances precision and provides the potential to increase the statistical power. In a simulation study, we demonstrated that this approach not only allowed more events per patient in the analysis but also in turn reduced the variance of the estimate and provided additional discriminative power9.

With the introduction of this novel approach to composite endpoints, we encourage current and future trialists to report the frequency of all events and to consider this more comprehensive analysis in the pre-specified analysis plan, including the a priori stakeholder evaluation of the relative weights. In addition to clinician-investigators, these stakeholders may include patients, sponsors, regulators and journal editors. This may have a particular impact in investigations with longer-term follow-up where non-fatal events have a greater window of opportunity to occur11. Beyond the single-study context, an extension of this approach to the synthesis of multiple studies should be considered in the future. By modifying our traditional approaches (and learning from Einstein’s statement) we can make the best use of all clinical data collected and advance our understanding of treatments and the diseases we study.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to P.W. Armstrong, MD, for his critical review of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.