Abstract

Aims: Zotarolimus-eluting stents (ZESs) have been shown to be safe and effective in randomised trials. We sought to report the clinical outcomes after implantation of ZES in real-world clinical practice.

Methods and results: ZES have been approved for clinical use in Singapore since April 2005. Until December 31, 2007, a total of 219 patients had undergone implantation of ZES. After excluding 11 foreign patients with whom contact was lost, 208 patients (246 lesions, 305 stents) formed the study cohort. A high-proportion of diabetic patients (n=90, 43.3%) was included. Recommended dual antiplatelet therapy was at least 3 months (n=147) for patients treated before or 12 months (n=61) after January 2007. As of January 2008, the median follow-up duration was 19 months (range: 1 to 33 months). There were 10 (4.8%) deaths, including 7 (3.4%) cardiac deaths. Myocardial infarction occurred in 11 (5.3%) patients. The numbers of patients requiring target vessel revascularisation and target lesion revascularisation were 10 (4.8%) and 5 (2.4%) respectively. Using the ARC definition, there were two cases of definite stent thrombosis on days 7 and 17, and one case of probable stent thrombosis on day 15.

Conclusions: In this real-world clinical experience, ZES was associated with a low incidence of adverse cardiac events at a medium follow-up of one and half years.

Introduction

The zotarolimus-eluting stent (ZES; Endeavor, Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) is the third drug-eluting stent approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use in the United States.1 This second-generation drug-eluting stent system combines the cobalt-alloy Driver StentTM (Medtronic Vascular,Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) with the antiproliferative agent zotarolimus and a biocompatible phosphorylcholine polymer coating. Preliminary data from first-in-man (FIM) and pivotal randomised clinical trials have shown that ZES is safe and more effective than a bare metal stent in reducing restenosis and repeat revascularisation.2,3 Although ZES is not the most potent drug-eluting stent in suppressing neointimal proliferation,4,5 a recent randomised study suggests that clinical outcomes among patients treated with ZES were comparable to those among patients treated by an existing drug-eluting stent.6 Four-year follow-up of the FIM study confirms the durability of the safety and efficacy.7 However, the cohorts of low-risk patients with single de novo lesions tested in these trials do not represent most of the procedures in real-world clinical practice. In most centres, ZES is being implanted for off-label indications, the outcomes of which are likely to be less favourable compared to those reported in clinical trials.8,9

In this regard, ZES have been approved and available for clinical use in Singapore since April 2005. The objective of this study was to present the long-term follow-up data of patients who have undergone implantation of ZES at our institution.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective study carried out in the National University Hospital (NUH) of Singapore. Following sirolimus-eluting stent (SES; Cypher, Cordis Corporation, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) and paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES; Taxus, Boston Scientific Corporation, Maple Grove, MN, USA), ZES became available for clinical use since April 2005. ZES was available in a range of sizes from 2.25 mm to 4.0 mm in diameter, and 8 mm to 30 mm in length. Up to December 31, 2007, a total of 219 patients have undergone implantation of ZES for the treatment of symptomatic coronary artery disease. Following the introduction and replacement by the next generation ZES, Endeavor Resolute drug-eluting stent system (Medtronic Vascular), at our institution we decided to report the clinical outcomes of patients treated by the original ZES.

There were no strict indications for drug-eluting stent implantation at our institution, but operators were recommended to limit the use of drug-eluting stents in situations where the risk of restenosis was perceived to be high, such as diabetes mellitus, small artery, long lesion, and in-stent restenosis. The selection among the different drug-eluting stents was up to individual operator. Apart from being discouraged in ST-elevation myocardial infarction, there were no restrictions on patient and lesion selection, as well as procedural strategy for ZES implantation. Our institution has an internal guideline for dual antiplatelet therapy following drug-eluting stent implantation, but the final prescription was decided by the clinician in-charge. During the initial period, at least three months of dual antiplatelet therapy was recommended after ZES implantation, which was in line with clinical trials. Since January 2007, following guideline issued by the FDA, the recommended duration had been prolonged to 12 months.10,11 Unfractionated heparin was the only anti-thrombin used. Weight-adjusted heparin was administered to achieve an activated clotting time of >300 seconds, or 200 to 250 seconds when an intravenous platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor was used.

Data collection and management

Clinical and procedural data (including offline quantitative coronary analysis, QCA) were prospectively entered on a web-based data entry form. Off-line QCA (stenosis analysis software, AI 1000, GE, Schenectady, NY, USA) was performed by an experienced angiographer. For each lesion, baseline and post-procedural QCA were performed. The minimal lumen diameter, reference diameter, percent diameter stenosis and lesion length were measured. All data were verified and the web-based data entry form closed by the interventional cardiologist performing the procedure. Off-label use of ZES was defined as implantation in left main coronary artery, saphenous vein graft, multivessel stenting, bifurcation lesion, chronic total occlusion, restenotic lesion, lesion length > 27 mm, or reference vessel diameter < 2.25 or > 4.0 mm. There was no mandatory angiographic follow-up protocol at our institution.

Follow-up

Retrospective follow-up data was collected by a dedicated research assistant at our institution. Information on patient outcomes was obtained by telephone calls, medical charts, and review of the web-based data entry form. Patients were evaluated for the occurrence of death, myocardial infarction, target vessel or lesion revascularisation (surgical or percutaneous revascularisation). Stent thrombosis was classified on two levels: time frame and event certainty. The time frame followed the traditional definition of acute (within 24 hours), subacute (1 to 30 days), late (>30 days to 1 year) and very late (> 1 year) stent thrombosis. The event certainty was based on the Academic Research Consortium (ARC) consensus definition (definite, probable or possible).12 Since no patient underwent mandatory angiographic follow-up, all the revascularisation procedures were symptom-driven.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). In the analysis of major adverse cardiac event, a patient was considered to have an event if he/she experienced any of the following: cardiac death, myocardial infarction or target lesion revascularisation, following the implantation of ZES. The event time was calculated from the date of procedure, to the date when a major adverse event first occurred. Patients who did not experience any major event were censored at the date of last follow-up. The cumulative probability of any major event was constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between groups of clinical interest were made using the log-rank statistic. The hazard ratio (HR) and its associated 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated to provide a measure of the effect. Cox proportional hazards regression was employed to assess independent correlates of adverse outcomes. All statistical tests were assessed at the conventional 0.05 level of significance.

Results

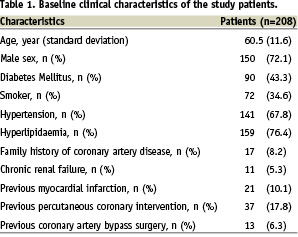

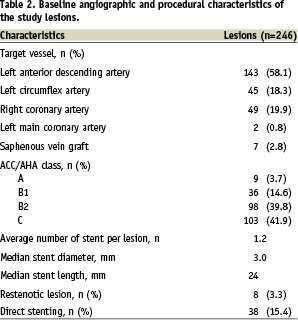

From April 26, 2005 to December 31, 2007, a total of 219 patients underwent implantation of ZES. During this period a total of 3,978 patients underwent coronary stent implantation at our institution, and 1,452 patients (36.5%) received drug-eluting stents. After excluding 11 foreign patients with whom contact was not available, 208 patients (246 lesions, 305 stents) formed the study cohort. The demographic and procedural data of the patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

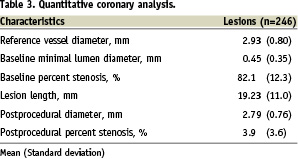

It is notable that approximately half (n=90, 43.3%) of the patients had diabetes mellitus. ZES was implanted for off-label indications in 161 (77.4%) patients. Importantly, left main lesions (n=2, 1%) and saphenous vein graft lesions (n=7, 4.3%) were also included in this analysis. Approximately one-third (n=72, 34.6%) of the patients received more than one stent. Glycoprotein IIbIIIa inhibitor was used in 11 (4.5%) patients. Quantitative coronary analysis data are shown in Table 3.

Anti-platelet therapy

Because of allergy or intolerance to aspirin, single antiplatelet therapy was prescribed in eight patients (clopidogrel, n=7, ticlopidine, n=1) after ZES implantation. All eight patients had ZES implanted during the initial period (within the first year) after approval.

The reminder of the patients (n=200, 96.2%) were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy on discharge. Despite internal guideline and trial use of at least three months dual antiplatelet therapy, the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy prescribed varied widely, from one month (n=8, 3.8%), three months (n=79, 38.0%), six months (n=36, 17.3%), to 12 months (n=73, 36.5%).

After the FDA recommendation on dual antiplatelet therapy for 12 months after drug-eluting stenting implantation was issued in December 2006, the percentage of patients prescribed with dual antiplatelet therapy for 12 months increased significantly (85.2%, n=52/61, after versus 15.6%, n=23/147, before, p<0.001).

In-hospital outcomes

Device success, defined as less than 50% stenosis and Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow, was achieved in all patients. Procedural success, defined as device success without an in-hospital major adverse event (death, myocardial infarction or urgent revascularisation) was achieved in 98.1% of the patients. There were four cases of post-procedural myocardial infarction, one due to stent edge dissection requiring urgent target lesion revascularisation while no identifiable cause was found in the other three.

Clinical follow-up

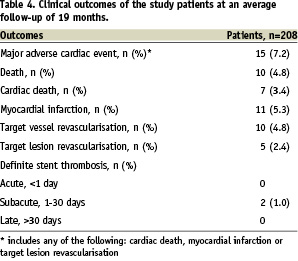

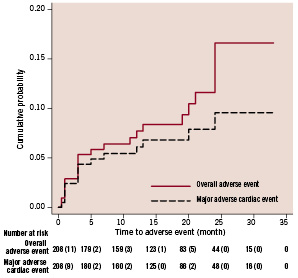

As of January 2008, the median follow-up duration was 19 months (range: 1 to 33 months). There were 10 (4.8%) deaths, including seven (3.4%) cardiac deaths. The three non-cardiac deaths consisted of carcinoma of the lung (n=1, 21 months post ZES implantation), carcinoma of the prostate (n=1, 24 months post ZES implantation) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (n=1, 24 months post ZES implantation). Myocardial infarction occurred in 11 (5.3%) patients. The number of patients who underwent target vessel revascularisation and target lesion revascularisation were 10 (4.8%) and five (2.4%) respectively. The overall adverse event (death, myocardial infarction, target vessel or lesion revascularisation) rate was 10.6%, and the major adverse cardiac event (cardiac death, myocardial infarction and target lesion revascularisation) rate was 7.2%. Table 4 summarises the adverse event rates and Figure 1 shows the event curve.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall adverse events (all death, myocardial infarction or target vessel revascularisation) and major adverse cardiac events (cardiac death, myocardial infarction or target lesion revascularisation).

Among the eight patients receiving only single antiplatelet therapy, there were two deaths (one cardiac and one non-cardiac), and there were no stent thromboses.

In univariate analyses, male gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure were found to be possible predisposing risk factors of major adverse cardiac events. Further analysis adjusting for the effect of potential confounders revealed male gender and chronic renal failure to be the two main predictors of major cardiac events. In particular, females have a higher risk of a major cardiac event (HR= 0.21; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.63; p=0.005). Chronic renal failure increased the risk of a major cardiac event (HR=5.52; 95% CI 1.71 to 17.87; p=0.004).

Stent thrombosis

According to the ARC definitions, the number of patient with definite, probable or possible stent thrombosis were two (1%), one (0.5%) and one (0.5%), respectively. For the two patients with definite stent thrombosis, the first patient was a 68 years old Malay female admitted with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Two ZESs were implanted to the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and one ZES was implanted to the proximal left circumflex artery. Three months of dual antiplatelet therapy was prescribed. She was readmitted 17 days later with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction due to thrombotic stent occlusion of the LAD. The second patient, whom we reported previously,13 was a 39 years old Chinese female with active systemic lupus erythematosus. She was admitted with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Four ZESs were implanted to the LAD. However, she stopped dual antiplatelet therapy immediately after hospital discharge and was admitted seven days later with subacute stent thrombosis, presenting as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Both patients, now 30 and 25 months respectively after the index procedures, remain alive with no further adverse events after the stent thrombosis events. One patient with probable stent thrombosis developed sudden death at home 15 days after ZES implantation, and the patient with possible stent thrombosis developed sudden death at home seven months after the ZES implantation. Post-mortem examination was not performed on these two sudden death patients.

Discussion

This is a retrospective study from an institution where ZES was approved for clinical use since April 2005. The main finding of this study is that ZES appears to be safe and effective in real-world clinical practice-where high-risk patients and complex lesions are treated. Importantly, although this is a relatively small study, there were no incidences of definite late stent thrombosis.

Compared to the SES and PES, ZES has several unique features that qualify it as a second-generation drug-eluting stent. The Driver stent™ platform (Medtronic Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA),14 made of cobalt-alloy, has one of the thinnest struts (91 µm) and is one of the most deliverable stents available. The drug (zotarolimus) is an analogue of sirolimus, which has been proved highly effective in SES.15 Most importantly, the biocompatible phosphorylcholine polymer16,17 has been shown in vitro to resist fibrinogen adsorption and cause less platelet and monocyte activation.18 Although speculative, these may improve the safety profile and reduce the risk of late stent thrombosis,19 which has been a major concern for first-generation drug-eluting stents. Pre-clinical data have shown that ZES is effective in suppressing neointimal proliferation and,20,21 compared to SES and PES, induced least amount of inflammation.22 In addition, all stent struts of the ZES were shown to be covered by neointimal tissue.22

In the pivotal Endeavor II study, the primary endpoint of target vessel failure at nine months was reduced from 15.1% with the bare metal stent to 7.9% with the ZES (P=0.0001), and the rate of major adverse cardiac events was reduced from 14.4% with the bare metal stent to 7.3% with the ZES (P=0.0001).3 Although, when compared with SES, ZES is associated with significantly higher late lumen loss (0.34±0.44 mm versus 0.13±0.32 mm, p < 0.001) and binary restenosis rate (11.7% versus 4.3%, p=0.04) at 8-month angiographic follow-up,4 a subsequent large-scale randomised study of 1548 patients focused on clinical endpoints demonstrated non-inferiority of the ZES compared to PES.6

Currently more than half of the SES and PES use are for off-label indications.8,9 It is conceivable that ZES would also be widely used for off-label indications in the US market. However, it is recognised that off-label use of SES and PES is associated with higher incidences of adverse events, including stent thrombosis.8,9 So far, there has been no report on long-term outcomes after implantation of ZES in real-world clinical practice. In this regard, our study provides valuable information because of the unique characteristics of our study population. The proportion of diabetic patients in our study was much higher than that in the randomised trials (43.3% versus 16.0-29.7%).2-4,6 Complex patient and lesion subsets such as chronic renal failure, left main disease, saphenous vein graft lesion, and in-stent restenotic lesions were excluded in randomised trials but were included in this study. In the majority of procedures (77.4%), ZES was implanted for off-label indications in this study. Despite these unfavourable factors, excellent clinical outcomes were observed at a median follow-up duration of one and half years. The 7.2% risk of major adverse cardiac event was low and was similar to that reported in clinical trials. While awaiting data from larger multicentre registries, our study suggests that it might be reasonable to extrapolate the clinical trial results of ZES into real-world clinical practice.

It is beyond doubt that stent thrombosis (especially late stent thrombosis) has been a major concern for first-generation SES and PES.23-28 Although the absolute event rate is low in most series, stent thrombosis often presents in a catastrophic manner with high incidence of myocardial infarction and/or death.29-31 In accordance with the pre-clinical findings mentioned before, data from Endeavor I-IV clinical trials point to a late stent thrombosis risk of 0.4% at one year and 0.5% at two years, rates similar to that for bare metal stents. In the present study, there were two cases of definite and one case of probable stent thrombosis, all occurring within the first month. The absence of definite late stent thrombosis, together with a low (1.4%, n=3/208) combined incidence of definite/probable stent thrombosis are promising. Given the low absolute incidence, long-term follow-up studies with a larger patient population to confirm these initial findings are warranted. The E-five registry enrolled more than 8,000 patients is designed for this purpose, but so far only short-term outcomes of a small proportion of the enrolled patients are reported. The 30-day major adverse cardiac event rate reported was 1.7%.32 It would take a few years before the long-term data are available. The PROTECT trial was designed to compare the safety (incidences of stent thrombosis) of ZES and SES in 8,000 patients at 200 international clinical sites. Results are expected to be available in 2010.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations in this study. This was a retrospective study at a single centre. There was no mandatory angiographic follow-up protocol at our institution. Therefore, data on angiographic parameters such as late loss and restenosis rate were not available. The number of patients in some subgroups, such as chronic renal failure and left main disease were too small to make meaningful sub-analysis. In an attempt to optimise the cost-effectiveness of using expensive devices at our institution, most drug-eluting stents (including ZES) were implanted in patients and/or lesion subsets at high-risk of restenosis. This may introduce bias when other centres having a different medical device reimbursement system are using our data as a reference. Since this was a real-world clinical experience but not a prospective randomised trial, only procedures where the ZES was actually deployed were included in the analysis. Situations such as when the ZES failed to reach or cross the lesion were not recorded, although we believe it should be a rare event.

Conclusions

In this real-world clinical experience with a high-proportion of off-label use, ZES was associated with low incidences of major adverse cardiac event at a median follow-up of 19 months. There were no incidences of definite late (beyond one month) stent thrombosis. While awaiting larger studies with longer follow-up, our study suggests that the safety and efficacy of ZES demonstrated in randomised trials can be extrapolated into real-world clinical practice.