Abstract

Percutaneous coronary procedures performed in a day-case setting are intended to facilitate an optimised resource allocation and increase patient satisfaction without compromising procedural and long-term safety or efficacy. While an increasing number of centres have implemented a day-case approach, patient pathways and procedural aspects still lack standardisation, potentially leading to a large heterogeneity in practices. However, several centres and healthcare systems are still reluctant to adopt day-case diagnostic or therapeutic coronary procedures because of safety concerns, penalising reimbursement policies, or simple inertia. This clinical consensus statement summarises experience-based know-how and research-derived data on day-case coronary procedures with the objective of providing standardised practical guidance on patient selection, procedural considerations, and postprocedural management to facilitate wide-scale adoption of a day-case coronary programme. The document also provides clear advice on when such procedures must be converted into regular admissions to maximise patient safety.

Over the last decade, an increasing number of percutaneous cardiovascular procedures have been performed as day cases (DC) – defined as cases in which admission, procedure, and discharge occur on the same day – primarily due to the need for optimising resource allocation and improving patient comfort12. Nevertheless, several centres and national healthcare systems are resistant to introducing DC pathways, mainly due to safety concerns and reimbursement policies.

Modern preprocedural diagnostics and latest-generation interventional tools and techniques allow procedures to be performed with high efficacy and reduced periprocedural risk, which can facilitate the diffusion of DC strategies in well-selected patients. Notwithstanding, local practices are mainly based on individual experiences, with marked heterogeneity between centres. Accordingly, standardisation of the DC approach for interventional coronary procedures would allow the definition of a widely accepted and safe pathway for pre-, peri-, and postprocedural patient management234. This standardisation would include (1) the identification of “best-fit” patient cohorts, clinical indications, and the type of procedures potentially suitable for provisional DC care; (2) the definition of minimum standards for DC care, focusing on procedural and patient safety; and (3) the definition of periprocedural developments that indicate a preferable or mandatory conversion to a regular overnight stationary admission.

The scope of this document is to share experience-, evidence- and data-based advice on how to optimise DC care of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary procedures with the aim of maximising patient safety and procedural efficacy, while optimising the logistics of the healthcare system.

Aims of a day-case strategy

The techniques, tools, and pharmacology related to coronary interventions have developed during the last decades, opening new opportunities for patient treatment while optimising resource allocation. The rationale behind a DC strategy is to minimise hospitalisation without any excess in procedural hazard. DC is beneficial for patients, in view of the reduced risk of in-hospital acquired infections as well as personal comfort, with the added advantage that the spared hospital resources can be better allocated.

Preprocedural evaluation

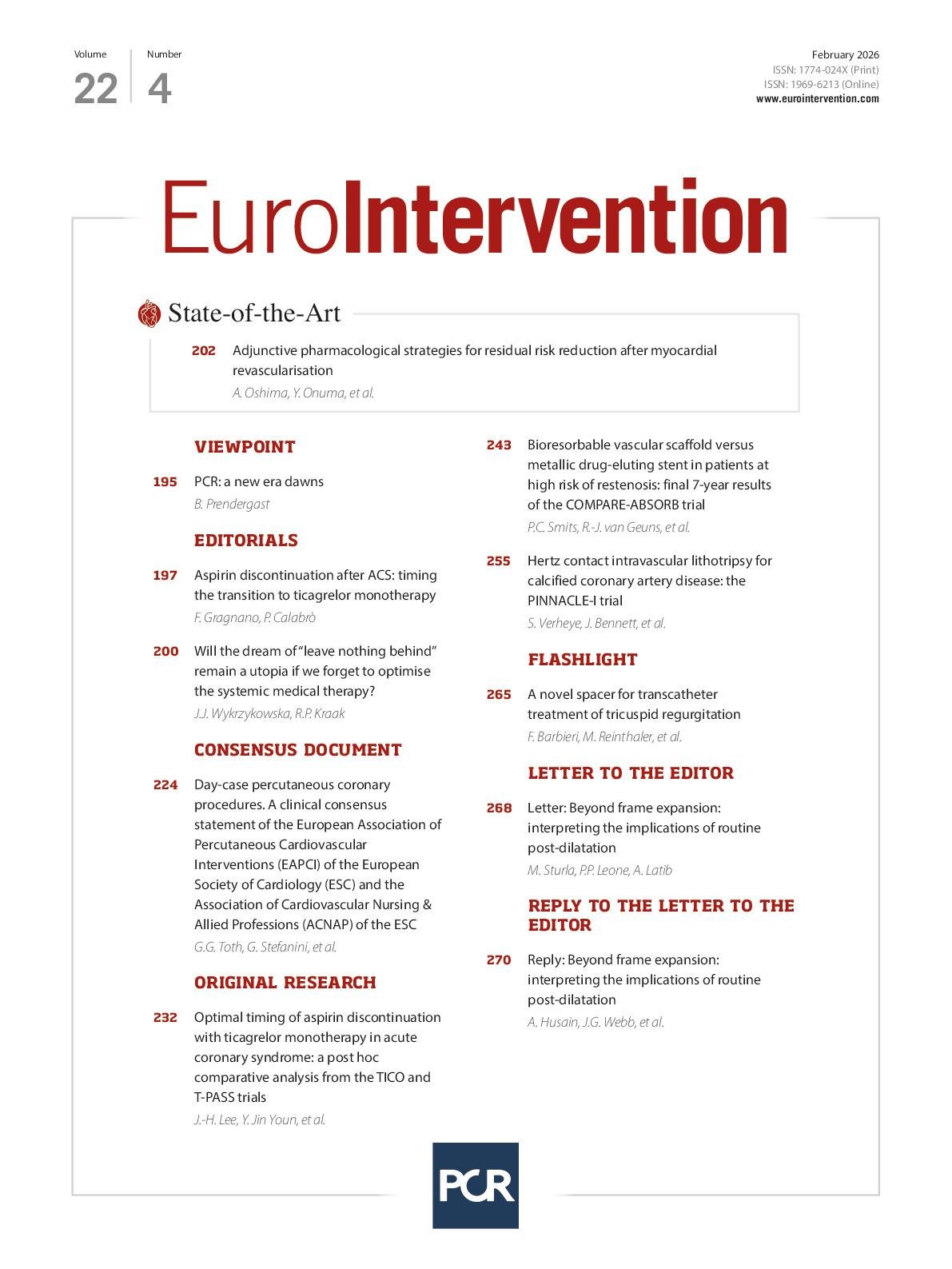

A thorough preprocedural assessment following a standardised protocol based on well-defined selection criteria is essential to ensure a successful DC programme. In addition to a standardised clinical assessment (including discussion of the planned procedure and comorbidities), factors such as potential social aspects, frailty, and health literacy have been suggested as more relevant in identifying suitable patients for DC procedures (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Periprocedural advice for day-case strategies. Strength of advice: IIII – clinical advice, based on robust published evidence; III – clinical advice, based on uniform consensus of the writing group; II – may be appropriate based on published evidence; I – may be appropriate, based on uniform consensus of the writing group. DC: day case; ECG: electrocardiogram; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Patient selection

Several studies have evaluated patient demographics and clinical characteristics related to DC procedures, including age567, sex8, educational attainment, ethnicity9, primary payor status (public healthcare system vs insurance)10 and case- and patient-specific variables (e.g., high-risk profile, comorbidities, renal impairment, cardiac status, multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI])6111213. While none of these aspects have been clearly associated with impaired outcomes, for hospital logistics and overall patient satisfaction, they should be taken into consideration when deciding between DC versus traditional overnight admission. Beyond these aspects, preprocedural evaluation and patient selection should also include a careful assessment of allergies (i.e., contrast, acetylsalicylate, nickel) since they might impact the planned procedure and postprocedural monitoring.

Moreover, risk factors for developing acute kidney injury following PCI should be assessed – including age, diabetes mellitus, acute indication, recent heart failure, baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, baseline anaemia, impaired left ventricular ejection fraction, and frailty141516. The risk of postprocedural nephropathy following a DC procedure can be attenuated by adequate patient selection and application of the general principles promoted by European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines17, including periprocedural hydration, suspension of nephrotoxic medication, and targeted, low-contrast use. The opportunity to propose a DC procedure to a patient with chronic renal failure (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) should take into consideration the above-mentioned factors, the patient's renal function, and the expected amount of contrast medium. Specifically, in case of patients with severe renal failure (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), a DC setting is reasonable in the case of coronary angiography but not necessarily in the case of PCI, given the need for pre- and postprocedural intravenous hydration for PCI17. In case of patients with moderate chronic kidney disease, a DC strategy could be feasible for coronary angiography and PCI where the expected contrast medium volume is below 100 mL17. In these latter cases, postprocedural intravenous hydration could be proposed during the observation time. In all cases, follow-up of renal function should be performed by measuring serum creatinine 24 h after the intervention, potentially in an ambulatory setting, to detect early signs of acute kidney injury16.

Social and logistical aspects

A comprehensive social history, including living situation, should be obtained as part of the preprocedural assessment. Not only is this an important part of a holistic approach to patient care but, considering that certain social standards of living are a prerequisite of a DC procedure, it will also highlight potential issues prior to the procedure, thereby minimising the need for additional workload later and potential patient dissatisfaction.

It is important to confirm that the patient agrees with the proposed DC9. Despite having a successful, uncomplicated procedure, a patient may prefer not to have a DC procedure for non-clinical reasons such as complicated acute access to a healthcare facility due to personal logistics (e.g., living far from a hospital, living alone with no support, etc.).

The presence of a caregiver − whether a health professional, a family member, or a friend − is essential after a DC hospital discharge to generally monitor the patient and to assist in case of need18. Despite very low complication rates in contemporary catheterisation procedures, potential delayed periprocedural adverse events, vascular access complications, and drug side effects (especially after use of opiates or sedatives) mandate the presence of a caregiver overnight after a DC procedure. In the rare case of a complication, emergency services should be alerted, and the patient should be referred to the nearest hospital facility.

Pragmatically, it is reasonable that a patient is accommodated within a one-hour travel distance from any hospital facility during the first postprocedural day, despite the lack of evidence on an ideal distance18.

Frailty status

Among patients with chronic coronary syndromes, frailty is known to be associated with increased risks of mortality, complications, and prolonged length of stay1920. Thus, assessment of frailty status should be performed as part of an individualised assessment of eligibility for a DC. Although there is no specific frailty score validated for the purpose, frailty status can support the treatment decision, including a potential need for overnight hospitalisation. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses emphasised the importance of routine frailty screening in risk stratification, especially among elderly patients referred for PCI2122.

Health literacy

The patient should be adequately informed on the nature of the procedure, risk of complications, importance of compliance with pharmacotherapy (in particular the post-procedure antiplatelet medication), and the planned follow-up. Previous studies have demonstrated how low health literacy is associated with worse outcomes2324. Health literacy can be systematically assessed using a validated patient-reported outcome measure, when relevant. To include health literacy perspectives into a DC practice, preprocedural information and detailed consenting, including necessary information about the post-discharge phase, should be individually adapted to each patient110.

Procedural indications

A provisional DC approach is reasonable for procedures performed without any relevant complication and that do not require extended monitoring18. An appropriate DC indication will depend on the anticipation of potential procedural complications and patient-related factors, therefore requiring a careful analysis of the patient’s medical history and the planned procedure before establishing eligibility25.

Coronary artery angiography is feasible as a DC, with no increased risk of complications reported18. The feasibility and safety of a DC after a planned or ad hoc PCI procedure have been evaluated and validated by different registries, prospective randomised trials, and meta-analyses1618. The PCI should ideally be elective, although ad hoc PCI might be proposed at the discretion of the operator in case of low lesion complexity25. Patients with acute coronary syndrome (either with or without ST-segment elevation) have been excluded from the majority of DC PCI studies and, in the absence of supporting evidence, should not be considered for a DC strategy.

Preprocedural medication

Patients who are already on antiplatelet therapy prior to the procedure should not interrupt it on the day of the procedure. An antiplatelet loading dose (600 mg clopidogrel preferentially one day before PCI) is advised in P2Y12 inhibitor-naïve patients in whom an elective PCI is planned1726. Assessment of high bleeding risk factors and PCI complexity may be used to customise the type and duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after the procedure17.

Among patients on oral anticoagulation, diagnostic coronary angiography and low-risk PCI can be performed without interrupting oral anticoagulation, by using radial access. For complex PCI, discontinuing anticoagulation is advised, but the decision should be eventually taken by the operator based not only on the ischaemic/bleeding risk of the patient/procedure but also on personal skills and experience. Oral vitamin K antagonists should be stopped three days prior to the procedure, eventually with heparin bridging if necessary, while non-vitamin K antagonist therapy can be stopped on the day of the procedure for once-daily drugs and 12 h prior to the procedure for twice-daily drugs.

Preprocedural laboratory tests

Recent preprocedural laboratory status is needed for all patients who undergo coronary catheterisation. A laboratory test not older than one month should be available at the time of the procedure. This should include blood status, coagulation status, inflammation status, renal function, and liver function. A newly identified or dynamic abnormality might indicate stricter postprocedural control or an overnight stay after coronary angiography.

Preprocedural echocardiography

A transthoracic echocardiogram should be available (ideally performed <6 months prior to the procedure) for all patients who undergo coronary angiography for an adequate clinical evaluation and risk stratification. Patients with heart failure symptoms, with high or increasing pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels, or with a newly discovered cardiac murmur since the last examination should be re-evaluated with transthoracic echocardiography prior to catheterisation.

Procedural aspects

Admission

At the time of admission, a double-check regarding the above-described criteria (i.e., most recent lab results, most recent echocardiography report, taken and paused medication, and allergies) is advised prior to the start of the procedure. While a fasting status is standard in most centres, the safety of a non-fasting status has been suggested27.

Access site

Radial access is consistently associated with a lower rate of bleeding complications compared to femoral access28. Moreover, radial access-related bleeding is easy to monitor and to manage out of hospital after discharge. Therefore, radial access is the gold standard in a DC programme, while distal radial and ulnar access represent advisable alternatives.

Of note, femoral access may still be used in patients undergoing coronary interventions according to the operators’ preference or if no suitable forearm access is available. When femoral access is used, a DC procedure is still possible, but haemostasis should be cautiously reviewed prior to discharge, and patients should be kept for a longer in-hospital postprocedural observation (i.e., 6 hours after the end of the procedure). An ultrasound-guided puncture is strongly advised in case of femoral access with a planned DC, since it increases first-pass success, ensures precise common femoral artery puncture, and reduces access site complications2930. For femoral access, the use of closure devices is encouraged because of a more rapid and more complete haemostasis283132. Prior to discharge, all patients should be informed of how to avoid all relevant groin or forearm exercises (e.g., climbing stairs) for the immediate postprocedural phase.

Type of procedures

There is no elective coronary procedure that by default contraindicates a DC approach. However, as discussed above, an individualised comprehensive assessment of patient characteristics and procedural aspects is pivotal to identify appropriate cases.

Diagnostic coronary angiography in a low-risk patient is a first-line indication for a DC. Persisting in a DC strategy is discouraged if a relevant procedural complication occurs (e.g., access site complication, contrast reaction, or contrast overload). In the event of significant findings during the coronary angiography, reassessment of a possible DC approach should be guided by the disease complexity and by the planned revascularisation strategy (i.e., ad hoc vs planned revascularisation; ad hoc complete vs staged complete revascularisation; interventional vs surgical revascularisation). If ad hoc revascularisation is performed and an adequate postprocedural observational time window is granted (at least 6 hours)3334, no benefit is expected from an overnight admission or longer hospitalisation.

Complex PCI procedures − such as multivessel PCI, complex bifurcation lesions, or calcified stenosis requiring adjunctive lesion preparation − should not be considered an absolute contraindication to a DC strategy. Retrospective registries have reported that rotational atherectomy-facilitated PCI, unprotected left main PCI and uncomplicated PCI of chronic total occlusions are feasible and safe in a DC setting3536373839404142. However, robust, prospective, and generalisable evidence is lacking. Currently, it is reasonable to advise that, in experienced centres, complex and high-risk PCI can provisionally follow a DC strategy if the procedure is successful and uncomplicated. Unsuccessful but uncomplicated cases may also be considered for DC (e.g., typically a failed attempt of a chronic total occlusion). On the other hand, in the case that procedural complications occur, including relevant coronary flow disturbance with expected periprocedural myocardial infarction, symptomatic arrhythmias, access site complications, or haemodynamic imbalance during the procedure, conversion into overnight admission is advised.

For procedures requiring significant contrast use (suggested >approximately 250 mL) or overall longer duration (suggested >approximately 150 minutes), a DC should be avoided because of medical, logistical, and patient-dependent factors. Therefore, for procedures with a higher probability of finally not fulfilling the DC criteria, a back-up option for overnight stay should be granted (Table 1).

Table 1. Procedural evaluation of day-case eligibility.

| Safe |

|---|

| Continuously maintained TIMI 3 flow |

| Asymptomatic patient during and after the PCI |

| No permanent or long-lasting ECG changes |

| No definite (side) branch occlusion |

| Non-complex coronary stenoses with an acceptable stent result |

| May be appropriate |

| Transient TIMI 1-2 flow without long-lasting patient symptoms or ECG changes |

| Complex and higher-risk interventions with confirmed acceptable stent result |

| Not advised |

| Estimated periprocedural myocardial infarction (e.g., persistent no-flow or TIMI 1 flow during the procedure, side branch occlusion, persistent ST-segment elevation, etc.) |

| Suboptimal stent result confirmed angiographically or by intravascular imaging |

| Haemodynamic instability during the procedure |

| Symptomatic patient after the procedure |

| Periprocedural persistent ECG changes as compared to baseline |

| ECG: electrocardiogram; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction |

Postprocedural assessment

On-the-day status

Postprocedural observation is a key element for a safe DC strategy. Following the procedure, clinical PCI success should be assessed utilising standard definitions, and any adverse event should be recorded. If the success criteria are not met, monitoring should be extended with overnight admission.

After the procedure, the patient should be routinely transferred to the DC ward, accompanied by medical personnel. All patients who are intended for a DC strategy should undergo routine postprocedural electrocardiography (ECG). Postprocedural continuous ECG and continuous blood pressure monitoring are not necessary. Sequential arterial pressure measurements are advised. Postprocedural echocardiography is not required, unless there is suspicion of complications.

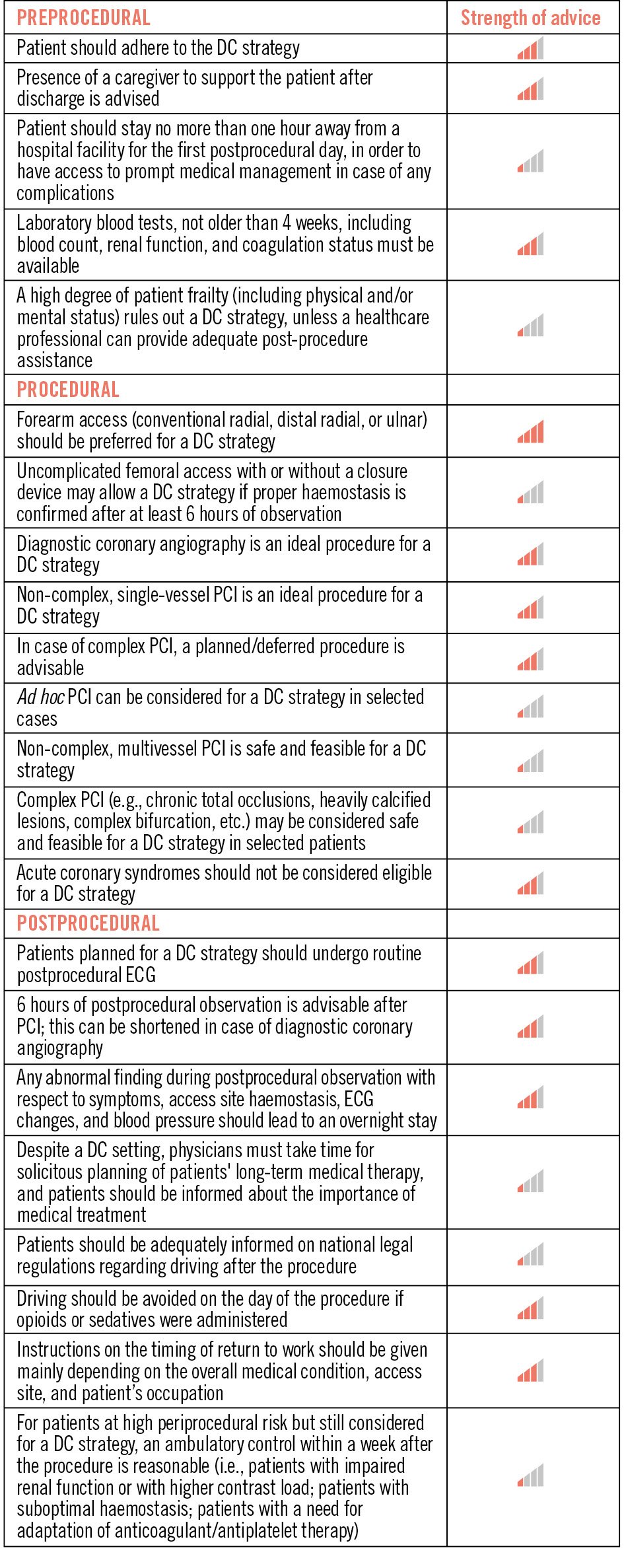

The usual hospital stay time for a DC varies, but a 6-hour observation time seems to be reasonable, considering that most periprocedural complications occur within 6 hours after PCI3334. The observation time may be decreased to 2-4 hours in case of pure diagnostic procedures, depending on the haemostasis policy. During that time, periodic observation, preferentially in the form of a checklist, for potential adverse events should be made. This includes checking for access site complications, for allergic reactions, for typical chest pain, for signs and symptoms of neurological deficit, for blood pressure beyond acceptable thresholds (systolic: 100-150 mmHg, diastolic: 70-90 mmHg), as well as for ECG changes and arrhythmias. Any abnormal finding in these respects should indicate overnight monitoring and potentially provisional next-day discharge. Validation of discharge should be made always by a well-informed healthcare professional (interventional cardiologist/clinical cardiologist/trained nurse) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proposed checklist for postprocedural day-case eligibility. ECG: electrocardiogram

Access site

Haemostasis and monitoring for vascular access site complications are critical for a DC procedure. Access site issues contribute to most side effects after PCI (1-16%) and, although minor in most cases, can be severe and result in relevant bleeding events. The latest haemostatic techniques, providing patent haemostasis for 2-4 hours with radial bands, should be used to further minimise complications. For transfemoral procedures, the postprocedural in-hospital observation phase should be extended at the discretion of the operator. Extensive patient education delivered by dedicated personnel (e.g., a trained nurse, advanced practice provider, physician assistant, clinical physiologist, pharmacist, or other qualified clinician – according to local organisation and competencies) regarding how to rest access sites during the post-discharge 24- to 72-hour period and how to recognise potential late complications is an essential element of a DC pathway.

Medications

While there is less opportunity for patient-physician interaction in a DC setting, it is still crucial that physicians take time to plan patients’ long-term therapies and that patients are instructed on the importance of medical treatment to optimise outcomes. The antithrombotic regimen should be defined prior to discharge (i.e., combination, potency, duration, de-escalation/escalation of DAPT, or triple antithrombotic therapy) following the current clinical practice guidelines43444546. If antiplatelet therapy is initiated during the DC procedure, a sufficient number of pills should be provided to the patient at the time of discharge, in order to cover the indicated dose for the following three days. For patients on oral anticoagulation who interrupted the anticoagulant therapy, the first dose of anticoagulant should be administered on the morning after the procedure in case of once-daily anticoagulants, and on the evening of the day of the procedure in case of twice-daily anticoagulants.

At the time of discharge, patients should receive a prescription for medication for secondary prevention and be well informed about its use and administration.

Post-discharge counselling

Clear and comprehensive instructions are required to ensure a safe post-discharge phase − to mitigate the risk of subsequent complications − and to increase awareness of health literacy.

Adequate wound care is important. Patients should be instructed on removal of access site dressings the day after the procedure. They can shower but must avoid baths or swimming for 5-7 days. They must avoid heavy lifting or strenuous activity for 3-7 days. If they experience bleeding or notice redness, pain, or swelling around the access site, they must contact a medical professional or the emergency services. The same applies to any suspected adverse event, such as chest pain, syncope, or dyspnoea.

Patients should be adequately informed – preferably in written form – on national legal regulations regarding driving after the procedure, which may vary based on the procedure performed, medications administered, and underlying medical condition. Driving is to be avoided on the day of the procedure if opioids or sedatives were administered.

Patients should be adequately informed on the timing of return to work, which primarily depends on the overall medical condition, access site, and patient’s occupation.

Post-discharge ambulatory follow-up

According to the ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes, regular cardiac follow-up is recommended45 for most patients who undergo coronary catheterisation, regardless of whether it is an overnight admission or a DC. For patients at high periprocedural risk but still considered for a DC, an ambulatory control within a week after the procedure is reasonable. Such ambulatory control can be advised with a focus on renal function (e.g., patients with impaired renal function or with a higher contrast load), access site (e.g., patients with suboptimal haemostasis, but without an indication for stationary admission), or adaptation of anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapy (e.g., patients who discontinued oral anticoagulation).

Financial considerations

DC programmes have economically favourable aspects47, but their profitability for an institution is still dependent on national and regional reimbursement policies. While the adaptation and optimisation of DC programmes is worth attempting, the discussion on cost-effectiveness falls beyond the scope of the present document due to its significant variations based on jurisdiction.

Conclusions

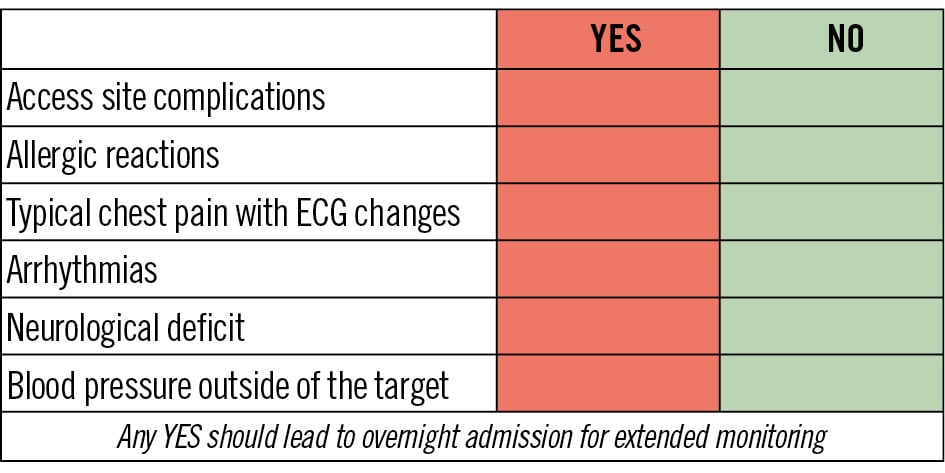

DC programmes allow for optimal resource allocation and increase patient satisfaction without compromising safety or efficacy. These programmes should be achieved through standardised pre-, peri- and postprocedural assessments of every individual patient, which are based on careful evaluation of patient- and procedure-related factors, including medical and social aspects. This document provides guidance on how to structure a DC programme for percutaneous coronary interventions (Central illustration).

Central illustration. Periprocedural assessment of day-case feasibility. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Conflict of interest statement

G.G. Toth reports speaker fees from Boston Scientific, Cordis, Terumo, and Medtronic. N. Amabile reports consulting fees from Boston Scientific, GE HealthCare, Abbott, and Shockwave Medical; and speaker fees from Boston Scientific and Abbott. E. Barbato reports consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences; and speaker fees from Boston Scientific, Abbott, Insight Lifetech, and Medtronic. T. Cuisset reports consulting and speaker fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Edwards Lifesciences. S. James reports research grants to the institution from Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. R. Al-Lamee reports consulting fees from Abbott, Philips, Shockwave Medical, Medtronic, and CathWorks; speaker fees from Abbott, Philips, Shockwave Medical, Medtronic, Fondazione Internazionale Menarini, and Servier Pharmaceuticals LLC; and support for attending meetings from Philips, Shockwave Medical, Medtronic, Abbott, Abiomed, Asahi Intecc, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardinal Health, Daiichi Sankyo, Teleflex, and Terumo. K. Mashayekhi reports consultancy fees and speaker honoraria (to the institution) from Abbott, Abiomed, Asahi Intecc, AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardinal Health, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Shockwave Medical, Teleflex, and Terumo. D. Regazzoli reports consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Terumo, and Medtronic. J.M. Siller-Matula reports a research grant from AOP Health; and speaker fees from Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, Biotronik, Boehringer Ingelheim, Terumo, and Cordis. S. Brugaletta reports consulting fees from Boston Scientific. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.