Abstract

Aims: To prospectively evaluate the benefit of upstream administration of eptifibatide in patients with non ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS) pretreated with aspirin and clopidogrel.

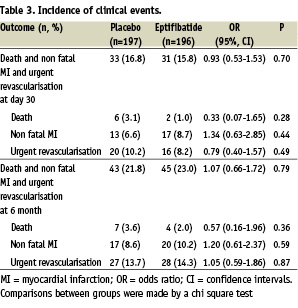

Methods and results: The PRACTICE study was an international, randomised, multicentre trial of 393 patients (of 766 planned) who presented with NSTEACS. Patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with eptifibatide (n=196) or placebo (n=197). Investigators used aspirin, clopidogrel with a loading dose of 300 mg followed by a daily dose of 75 mg, and heparin (unfractionated or low molecular weight) in both groups. An invasive strategy was planned within 6 to 48 hours. The primary endpoint was a composite of death, myocardial infarction, or urgent revascularisation at 30 days. The primary end point occurred in 31 patients (15.8%) in the eptifibatide group and in 33 patients (16.8%) in the placebo group (odds ratio 0.93, 95 percent confidence interval 0.53 to 1.53, P=0.70). The overall incidence of bleeding was not significantly different in the eptifibatide and the placebo groups (14.4% vs 11.3%, p=0.35).

Conclusions: We did not find a measurable benefit of upstream administration of eptifibatide on top of aspirin and clopidogrel in patients presenting with NSTEACS managed by an invasive strategy. Further studies are warranted to further evaluate the clinical benefit of upstream eptifibatide in patients pretreated by clopidogrel in a larger population.

Introduction

Antiplatelet therapy, in association with heparin, is the cornerstone of the management of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS). Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor (GP IIb/IIIa) inhibitors have been extensively evaluated in NSTEACS1-7. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials showed a strong benefit of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in this context, which appeared strengthened in patients with elevated troponin levels undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)8. However, until recently, none of these trials incorporated routine use of clopidogrel, and the demonstration of the efficacy of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with elevated troponin has been based mostly on post hoc subgroup analyses4-6. The CURE and the PCI-CURE trials subsequently demonstrated that clopidogrel in combination of aspirin was highly beneficial in NSTEACS, and the results suggested that pretreatment of clopidogrel may reduce the requirement of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors during PCI9,10. In other settings, such as low risk PCI, a strategy of dual oral antiplatelet therapy using a high loading dose of clopidogrel and aspirin, yields similar clinical outcomes to those obtained with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors11,12. The benefit of downstream administration of abciximab (i.e., in the cath lab), in the context of routine use of clopidogrel, has been recently reported in patients with NSTEACS in the ISAR-REACT 2 trial13. However, the benefit of upstream administration of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors (i.e., in the coronary care unit) in combination with clopidogrel has never been evaluated. The aim of the PRACTICE trial was therefore to prospectively evaluate the benefit of upstream administration of eptifibatide in combination with aspirin and clopidogrel in patients with NSTEMI planned to an early invasive strategy.

Methods

Patients

PRACTICE was an international, multicentre, randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover-permitted, clinical trial conducted in 46 tertiary hospitals (34 in France, 5 in Israel, 4 in Spain, 2 in Denmark, and 1 in Germany). This study was coordinated by the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou in Paris (France), and promoted by Schering Plough. The protocol was approved by relevant institutional review boards, and a written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were recruited between September 2001 and July 2004. Patients were eligible for the study if they presented with ischaemic chest pain at rest within the last 24 hours associated with ECG changes (ST-segment depression > 1 mm and /or negative T wave and /or transient ST-segment elevation) and an elevated cardiac troponin I or T. Each centre used its own cut-off for troponin I or T measurements without core laboratory. Reasons for exclusion were: persistent ST-segment elevation > 1 mm, recent myocardial infarction < 14 days, contra-indications to the administration of eptifibatide (prothrombin time > 1.2 times control, International Normalised Ratio > 2.0), evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, gross genitourinary bleeding or other active abnormal bleeding within the previous 30 days of treatment, uncontrolled hypertension with systolic blood pressure > 200 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure > 110 mm Hg, major surgery or severe trauma within the past 6 weeks, known history of stroke within the past year or any haemorrhagic bleeding, thrombocytopenia (< 100,000 platelets/mm3); creatinine clearance < 30 ml/min or serum creatinine > 350 µmol/l), hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients of eptifibatide concomitant or planned administration of another parenteral GP IIb/IIIa antagonist, patient unable to fully evaluate the potential benefits and risks of participation in this study, concomitant severe or potentially lethal diseases associated with shortened life expectancy, or pregnancy. In women of childbearing potential, effective methods of contraception or negative pregnancy test were required before inclusion.

Study protocol

Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were randomised in a double-blind manner to either eptifibatide or placebo in the coronary care unit using a prospective randomisation schedule. Eptifibatide or placebo infusion was started immediately after the randomisation. The eptifibatide arm patients received a single 180 µg/kg bolus followed by a continuous 2.0 µg/kg/min infusion, and the placebo group patients, a matching placebo. The infusion was continued for a maximum duration of 72 hours or up to 24 hours following PCI in those patients who underwent PCI during that period.

During the study, investigators were encouraged to systematically use aspirin, clopidogrel with a loading dose of 300 mg followed by a daily dose of 75 mg, and heparin (unfractionated or low molecular weight) in both groups. An invasive strategy was planned within 6 to 48 hours.

In order to provide emergency open-label glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy in case of abrupt closure, no reflow or slow flow (TIMI grades 1 or 2), need for urgent revascularisation or other similar PCI complications, bailout kits were supplied. Investigators had the possibility to break the randomisation code in order to assess the treatment group (placebo or eptifibatide). If placebo, an open bail-out kit (bolus and infusion) was available. If eptifibatide was given, no changes in the treatment were required.

Other treatments, including type and dosage of anti-anginal treatments were left at the investigators discretion. In order to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding, use of proton pump inhibitors was recommended.

If the patient required urgent cardiac surgery during eptifibatide or placebo therapy, the infusion was immediately stopped. If the patient required semi-elective surgery, the eptifibatide or placebo infusion was stopped at an appropriate time to allow time for platelet function to return towards normal (usually 4 hours).

Definition of study end points

The primary end point of the study was the incidence of death, myocardial infarction, and recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularisation at 30 days following randomisation. The secondary end points of the study were the incidence of death, non fatal myocardial infarction, and recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation at hospital discharge and at 180 days.

The diagnosis of MI was defined as follows: occurrence of Q-wave in two contiguous leads and/or increase in CK and/or CK-MB > 2 fold the upper limit of normal (ULN) values. In patients undergoing angioplasty, myocardial infarction was defined as an increase in CK and/or CK-MB > 3 fold the ULN values; in those undergoing CABG, MI was defined as the occurrence of Q-wave in at least two contiguous leads and/or increase in CK and/or CK-MB > 5 fold the ULN values. In patients presenting with elevated CK values at the time of randomisation, reinfarction was defined as the occurrence of a Q-wave in at least two contiguous leads and /or new increase in total CK and/or CK-MB > 50% previous value. Recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation was defined as the reoccurrence of anginal pain and/or ECG changes (new ST-segment depression, negative T-wave, transient ST-segment elevation, extension to other territories of baseline ECG abnormalities) requiring an angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

The safety of the study medications was assessed on the basis of the incidence of major and minor bleeding, profound thrombocytopenia (less than 20,000 platelets per cubic millimetre). Major and minor bleedings were defined according to the TIMI criteria14. All major cardiac events and bleeds were adjudicated by an event-adjudication committee whose members were blinded to assigned treatment.

Statistical analysis

Power calculation was based on the event rates reported in CAPTURE, PRISM, and GUSTO IV-ACS studies, which included patients with an acute coronary syndrome and positive troponin4,5,7. In the placebo groups of CAPTURE and PRISM trials, the occurrence of the combined endpoint of death, MI, and recurrent ischaemia at 30 days was 19.6% and 13.0%, respectively4,5. In the group of patients treated with a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor, the combined endpoint were respectively 5.8% and 4.3%, meaning an approximate 70% reduction4,5. In the GUSTO IV-ACS trial, the occurrence of death and MI at 30 days was lower than in the CAPTURE and PRISM studies (8.0% in the placebo group and 8.2% in the GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor group)7. Assuming an 11% incidence rate of the combined endpoint (death, MI, and recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation) under placebo versus 6% under eptifibatide (reduction > 40%) with an 80% study power and a one-sided α value of 5%, the required number of patients per group was 383.

Double data entry was carried out. Source data verification was implemented in order to detect any data discordance. Major adverse cardiac events (death, MI, recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation) were registered at discharge, 30 and 180 days by an independent, blinded, clinical events committee.

Because enrolment was slower than expected, the study was stopped by the promoter of the study in July 2004. At this time 393 patients had been enrolled, 196 and 197 in the placebo and the eptifibatide groups, respectively.

Primary efficacy analysis involved all randomised patients on an intention-to-treat basis. The characteristics of patients between groups were compared using a Pearson χ2 and ANOVA tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for critical events associated with treatment were estimated by logistic regression. Time to critical events by treatment group was compared by Log-rank tests (Kaplan-Meier method). P value for determination of the significance of results was 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.2 (SAS institute, Inc.).

Results

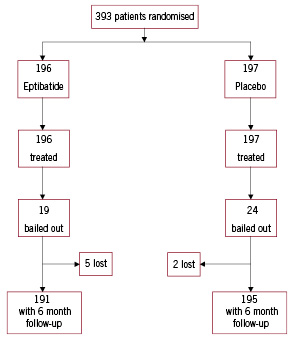

The flow of patients through the trial is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Trial profile.

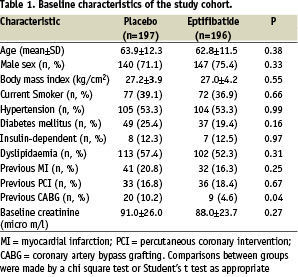

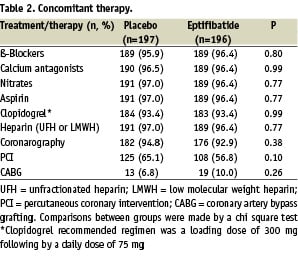

Of the 393 patients enrolled in the study, 196 were assigned to eptifibatide and 197 to placebo. Five patients were lost for the follow-up in the eptifibatide group and 2 in the placebo group (p=0.28). The overall follow-up was available in 98.2% of the randomised patients. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1, and are well balanced, although a history of CABG was significantly more frequent in the placebo group. Concomitant treatments are summarised in Table 2.

Aspirin, clopidogrel, and heparin (unfractionated and low molecular weight) were routinely and similarly used in both groups. Coronary angiography was performed within 48 hours of admission in more than 90% of the patients in both groups. Moreover, PCI and CABG were often and equally performed in both groups (Table 2). A bail out procedure was requested in 12.2% (24 patients) and 9.7% (19 patients) in the placebo and the eptifibatide groups, respectively (P=0.42). The 24 patients of the placebo group received open-label eptifibatide. Among these patients, the overall event rate of the primary composite endpoint 30 days after enrolment was 36.8% in the eptifibatide group (7 patients) and 29.2% in the placebo group (7 patients, p=0.59).

Efficacy analysis

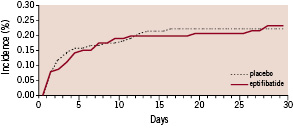

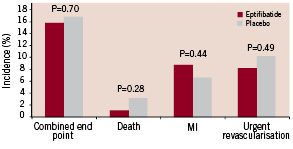

The results are summarised in Table 3 and in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2. The 30-day cumulative probability of the primary combined end point (death, myocardial infarction, recurrent ischaemia requiring urgent revascularisation) in the eptifibatide and placebo groups.

Figure 3. The 30-day incidence of adverse events in the eptifibatide and placebo groups. There were no significant differences between groups.

The overall event rate of the primary composite endpoint 30 days after enrolment was 15.8% in the eptifibatide group (31 patients) and 16.8% in the placebo group (33 patients, p=0.70). Death occurred in 1.0% in the eptifibatide group (2 patients) and 3.1% in the placebo group (6 patients, p=0.28). Non fatal myocardial infarction occurred in 8.7% in the eptifibatide group (17 patients) and 6.6% in the placebo group (13 patients, p=0.44). Sixteen patients (8.2%) in the eptifibatide group and 20 patients (10.2%) from the placebo group required urgent revascularisation. The results were closely similar at discharge (not shown) and 180 days after inclusion (Table 3). The primary composite end point at 30 days was also evaluated according to PCI status. In patients treated by PCI, the event rate of the primary composite endpoint 30 days after enrolment was 15.2% (19 patients) in the eptifibatide group and 14.8% (16 patients) in the placebo group (odds ratio 0.96, 95 percent confidence interval 0.47 to 1.99, P=0.84). In patients non treated by PCI, the event rate of the primary composite endpoint 30 days after enrolment was 17.1 (14 patients) in the eptifibatide group and 20.9% (14 patients) in the placebo group (odds ratio 0.75, 95 percent confidence interval 0.33 to 1.73, P=0.55).

Safety analysis

The overall incidence of bleeding was 14.4% (28 patients) in the eptifibatide group and 11.3% (22 patients) in the placebo group (p=0.35). Eight patients (4.1%) in the eptifibatide group and 6 patients (3.1%) in the placebo group had a major bleeding complication (p=0.59). Twenty patients (10.2%) in the eptifibatide group and 16 patients (8.1%) in the placebo group had a minor bleeding complication (p=0.48). Profound thrombocytopenia occurred only in one patient in the eptifibatide group.

Discussion

The latest American and European guidelines recommended to use GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients presenting with NSTEACS in patients with elevated troponin levels treated with an invasive strategy15,16. However, until recently, the trials did not incorporate routine use of clopidogrel, and the demonstration of the efficacy of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with elevated troponin has been based mostly on post hoc subgroup analysis. Moreover, physicians do not fully comply with the guidelines based on the assumption that a dual oral antiplatelet therapy combining aspirin and clopidogrel might be able to obviate the need for GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Two regimens of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors have been proposed in the management of patients presenting NSTEACS. GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors can be administered upstream or downstream to PCI if an early invasive strategy is planned. In the context of routine use of clopidogrel, the PRACTICE trial evaluated the effect of upstream administration of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor in patients presenting NSTEACS treated by an invasive strategy. We observed a small and non significant reduction of the primary combined endpoint in patients treated by eptifibatide compared with placebo. Our study was underpowered to detect a significant reduction since only 393 (out of planned 766) patients were included in the PRACTICE study. However, the small reduction of the primary end point may be also explained by the widespread use of clopidogrel in both groups. In the present study, clopidogrel was administered with a loading dose of 300 mg at least 6 hours before coronary angiography and PCI if necessary followed by a daily dose of 75 mg. In the CURE trial, clopidogrel was beneficial in combination with aspirin in NSTEACS9. The benefit was consistent across subgroups, particularly with regard to revascularisation9. In the PCI-CURE trial, a strategy of clopidogrel pretreatment followed by long-term therapy reduced cardiovascular events in patients with NSTEACS undergoing PCI10. In this trial, however, the use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors was discouraged unless refractory ischaemia occurred10. Moreover, fewer patients assigned to clopidogrel received GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors during PCI than those assigned to placebo (20.9% vs 26.6%, p=0.01) suggesting that pretreatment of clopidogrel and aspirin may reduce the requirements of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors10.

Two studies recently evaluated the benefit of downstream administration of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with NSTEACS13,17. ISAR-REACT 2 was an international, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial comparing abciximab with placebo13. All patients were pretreated with aspirin and clopidogrel (loading dose of 600 mg at least 2 hours before PCI, and followed by a daily dose of 75 mg), and were randomly assigned to abciximab (bolus of 0.25 mg/kg, followed by an infusion of 0.125 µg/kg/min for 12 hours) or matched placebo13. The recommended strategy was an early invasive strategy with PCI within 6 hours. The primary end point was a composite of death, non fatal MI, urgent target vessel revascularisation at 30 days13. The cumulative incidence of the primary end point was 11.9% and 8.9% in placebo and abciximab groups, respectively (relative risk 0.75, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 0.97, p=0.03). The benefit of abciximab was confined to patients presenting an elevated troponin level13. The ADVANCE study was a single centre, double blind, placebo controlled, randomised trial comparing tirofiban with placebo17. All patients were pretreated with aspirin and clopidogrel (loading dose of 300 mg followed by a daily dose of 75 mg), and were randomly assigned to tirofiban (high dose bolus of 25 µg/kg per 3 min, followed by an infusion of 0.15 µg/kg/min for 24 to 48 hours) or matched placebo17. The primary end point was a composite of death, non fatal MI, urgent target vessel revascularisation, and thrombotic bailout GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy at 180 days15. The incidence of the primary end point was 35% and 20% in placebo and tirofiban groups, respectively (hazard ratio 0.51, 95% confidence interval 0.29 to 0.88, p=0.01)17. The results of these 2 studies strongly suggest that downstream administration of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor is significantly associated with clinical benefit on top of aspirin and clopidogrel in patients presenting with NSTEACS managed by an early invasive strategy. Upstream administration of dual (aspirin and clopidogrel) versus triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, and tirofiban) has been recently reported in the ELISA-2 trial18. The primary end point of the study was enzymatic infarct size, which was not significantly different between the two regimens, although there was a trend towards a better survival without death or MI in triple antiplatelet therapy group18.

The only head to head comparison of upstream and downstream administration of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor has been recently reported in the EVEREST trial19. Tissue level perfusion and troponin release were significantly lower with upstream tirofiban compared to downstream tirofiban or abciximab19. However, this study was not designed to evaluate the clinical benefit of these two strategies in this clinical context. Further studies are warranted to compare upstream and downstream administration of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor in a larger population in this clinical context.

The safety analysis of the combination of aspirin, clopidogrel and eptifibatide was reassuring since we did not observe a significant increase of the overall incidence of bleeding in the eptifibatide group as compared to the placebo, according to recent trials13,17,18.

Limitations

Half of the expected patients have been enrolled. The study was stopped by the promoter of the study because enrolment was slower than expected. Our study was therefore underpowered to detect a clinical benefit of eptifibatide in this clinical context. The effect of upstream administration of eptifibatide in patients presenting with NSTEACS on top of aspirin and clopidogrel is currently evaluated in a larger population in the EARLY-ACS trial20.

We have probably overestimated the benefit of eptifibatide in the design of the study with an estimation of 48% odds reduction. However, this calculation was based on the analysis of the benefit of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in relation to serum troponin levels in the CAPTURE and PRISM studies4,5 demonstrating a 70% reduction of the primary endpoint in patients treated by GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors compared to placebo.

Finally, eptifibatide was administered in the present study with a single bolus of 180-µg/kg followed by an infusion of 2.0 µg/kg per minute according to the PURSUIT trial regimen3. Enhance inhibition of platelet aggregation with a double bolus administration of eptifibatide may further reduce ischaemic complication in NSTEACS21.

Conclusions

We did not find a measurable benefit of upstream administration of eptifibatide on top of aspirin and clopidogrel in patients presenting with NSTEACS managed by an invasive strategy. Further studies are warranted to further evaluate the clinical benefit of upstream eptifibatide in patients pretreated by clopidogrel in a larger population.

Appendix

Writing Committee: N. Danchin, E. Durand, A. Lafont, G. Steg.

Steering Committee: P. Barragan, P. Goldstein, E. Durand, A. Lafont.

Clinical Events Committee: N. Danchin, J.L. Dubois-Rande, P.G. Steg.

Study Centres, principal investigators, and study coordinators.

France

Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris (N. Danchin, E. Durand, A. Lafont, F. Ledru, S. Rahal); Clinique Beauregard, Marseille (P. Barragan, J.L. Bouvier, P. Commeau, P.O. Roquebert); Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire Rangueil, Toulouse (C. Beixas, P. Galinier, L. Schmutz); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nîmes (J.P. Bertinchant, J. Brunet, P. Messner); Centre Hospitalier de Poissy (J.C. Kahn, X. Marchand, M. Pathe); Hôpital Antoine Béclère, Clamart (P. Colin, S. Dinanian, T. Fourmet, I. Moraru, M. Slama); Centre Hospitalier de Chartres (F. Albert, G. Range); CHU - Hôpital Gabriel Montpied, Clermont-Ferrand (J. Cassagnes, C. Dauphin, J.R. Lusson, P. Motreff); Hôpital de Gonesse (M. Ghannem); Clinique des Franciscaines, Nîmes (P. Rioux, O. Wittemberg); Hôpital Cochin, Paris (P. Allouch, F. Belaouchi, E. Salengro, C. Spaulding); Centre Hospitalier Privé Saint-Martin, Caen (J.F. Morelle, A. Richard); Centre Hospitalier de Montmorency (A. Akesbi, G. Karillon); Complexe Hospitalier du Bocage, Dijon (Y. Cottin, J.C. Eicher, M. Freison, I. L’huillier, J.E. Wolf); Hôpital Nord de Marseille (F. Paganelli); Hôpital du Haut Lévêque, Pessac (P. Coste, C. Jaïs, R. Roudaut); Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil (S. Champagne, J.L. Dubois-Rande, P. Garot, J. Lacotte, I. Macquin-Mavier); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Necker, Paris (J.P. Metzger, C. Lefeuvre); Centre Hospitalier d’Avignon (S. Andrieu, J.L. Hirsch); Centre Hospitalier de Montfermeil (S. Cattan, P. Michaud, O. Nallet, J. Sergent); Centre Hospitalier de Versailles, Le Chesnay (J.L. Georges, B. Livarek, J.P. Normand); Centre Hospitalier de Pontoise (F. Funck, P. Jourdain); Centre Chirurgical Marie-Lannelongue, Le Plessis-Robinson (C. Caussin, G. Dambrin, B. Lancelin); Centre Hospitalier du Mans (D. Fagart, M. Rosak); Centre Hospitalier Général Bretagne Sud (P. Cazaux, J.P. Hacot); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Arnaud de Villeneuve, Montpelier (F. Leclercq, J.C. Macia); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Reims (C. Brasselet, J. Elaerts, D. Metz); Hôpital de Hautepierre, Strasbourg (P. Bareiss, G. Roul); Clinique Ambroise Paré, Boulogne (G. Makowski, F. Beverelli, R. Pilliere, O. Hoffman); Centre Hospitalier Général de Valenciennes (J.C. Bodart); Centre Hospitalier intercommunal de Toulon (I. Canavy); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Lariboisière, Paris (P. Henry).

Germany

Kerckhoff Heart Centre, Bad Nauheim (C.W. Hamm).

Spain

Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid (C. Macaya); Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander (J. Domenech); Hospital Clínico de Santiago de Compostela, La Coruna (J.M. Garcia Acuna); Hospital Virgen de Arrixaca, El Palmar, Murcia (M. Valdes); Hospital General de Cataluña, San Cugat del Vallés, Barcelona (C. Crexells).

Denmark

University Hospital of Aarhus (S.E. Husted); Hillerod Hospital (J. Launbjerg).

Israel

Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem (M. Mosseri); Kaplan Hospital, Rehovot (X. Piltz, O. Kracoff, L. Krasov); Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv (S. Viskin); Ha’Emek Medical Center, Afula (S. Atar); Hadassah Medical Center, Mt. Scopus, Jerusalem (A.T. Weiss).

Statistical analysis: X. Jouven (Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris).

Schering-Plough: I. Dreyfus, A. Rimailho.

References