Forgive me this “seaside” editorial but, if we do not digress a bit in July, when should we do it? Let’s discuss a topic that everyone knows and very few talk about. What is the action that most of us perform every day automatically, over and over again, without thinking too much? Yes, correct, I’m talking about the cancellation of the countless unsolicited, non-legitimate e-mails which have accumulated overnight and during the day. The phenomenon of medically themed spam began gently a few years ago and has progressively reached unsustainable proportions. I do not know how many of you have ever read these e-mails from A to Z, so seductive in promising high-impact publications with a large overall reach. If you have never done so, then you have missed wonderful peaks of creativity. Here are my top five favourite types of spam e-mail in the academic field.

Fifth position: those that have nothing to do with your specialty of interest

“We are pleased to invite you to submit your valuable research work in the (random non-cardiological) journal”. Thank you, sirs, your pleasure in inviting me is nothing compared to my pleasure in receiving twenty other e-mails of this kind every day. Typically, these journals try to attract the recipient with a list of newly accepted articles, which have nothing in common with disciplines even remotely or vaguely related to each other. “The Influence of the Tannic Acid on the Expression of the Connexins 45 in a Rat Kidney Damaged by the Chronic Hyperglycaemia” is certainly a respectable theme, but not exactly what I would call “my cup of tea”.

Fourth position: those who think they are very smart

The devil is in the detail, to quote an old saying. Indeed, once that first and quite legitimate pride of being invited to contribute to a scientific (?) journal has died down, the critical eye begins to look at the fine print and consider the rip-off. In fact, it must be said that these e-mails are always similar, so it is not that difficult to separate the useful from the useless. However, any distraction can be fatal. It goes without saying that most of these journals are not indexed, typically fake, and have no review process. Clicking the link by which you access the journal’s page on its charge policy, a world of tax after tax is revealed. In practice, not only is the journal unknown and perhaps even non-existent, but also the article’s topic is a shameless pretext. Even given (but not granted) that the article is finally written by a valiant fellow desiring to build his curriculum vitae, to publish it he or she will still have to borrow the equivalent of a mortgage.

Third position: those who invite you to write a book

Who has never wanted to write a bestseller? Some publishers give you the chance. Obviously, you have to write the whole index by yourself, and this is okay. Then you have to identify the authors of the individual chapters, and this is also part of the game. At that point, however, you have to explain to the co-authors, before it is too late, that the book is “open access” and therefore accepting authorship will mean at some point providing the publisher with a fair amount of money. In the end, the problem is not actually the journal that invites you, because the money request is after all quite explicit (well, sometimes it is not). The real problem is the colleague who receives his/her first invitation to be editor and tries at all costs to convince you to write a chapter, ignoring the issue of page charge. You try hard to explain that life is already complex enough and we do not need to add page charges to it, but for some reason he/she feels offended.

Second position: those who never give up

“Dear Researcher, I contacted you earlier regarding the manuscript submission for our journal but unfortunately we did not receive any response from your end. We are aware that you might be busy with your activities and so we are taking the liberty of sending the e-mail again”.

Of course, please feel free to send me the reminder another six times: if I did not answer it, it was certainly a case of my being distracted. Some journals are so desperate that they propose deadlines outside of any human logic: “You are welcome to submit your Research/Review/Rapid Communication, etc. [etc.?] within one week”. Obviously, if you were so “busy” as not to answer their previous e-mails, all of a sudden you are now somehow free to write and send an article within seven days.

First position: those who invite you to a wonderful congress

Leaving aside the theme of the congress itself (I often receive invitations to bioengineering stuff that I even struggle to pronounce), the interesting point is that such invitations invariably come under the heading of “first come, first served”. In practice, the invited pseudo-faculty must choose in perfect autonomy the session where he/she wants to talk, starting from a bunch of possible offers, and then insert the title of the presentation wherever it happens. The sessions are as predictable as a soup, ranging from astrophysics to antiplatelet therapy. Nothing is said about the financing of the registration, accommodation and travel costs. Of course, the appeal of the destination is not trivial and, to make everything more attractive, they range from the Caribbean islands to Alpha Centauri. “Awaiting your swift and favourable response”. Who could ever refuse?

Honourable mentions (off the chart)

a) Those who send the e-mail to you but the e-mail is addressed to another person.

b) Those who write to you in 2018 because they found your 2008 article of great interest.

c) Those who have read your “valuable” article on left main revascularisation and found it to be of great interest, so now they invite you to write in their journal of lymphology.

d) Those who invite you to review an article and say that “your commitment would be very much appreciated to ensure the highest standards of the journal” but, before thinking about the high standards of their journal, they really need to start looking at the standards of their own invitation letters.

e) Those who mix famous names or improbable words in their titles to look like high impact factor journals (“Journal of Blood, Circulation and Whatever”, “New England Journal of Cardiology”, “Journal of that organ that stays in the mediastinum”).

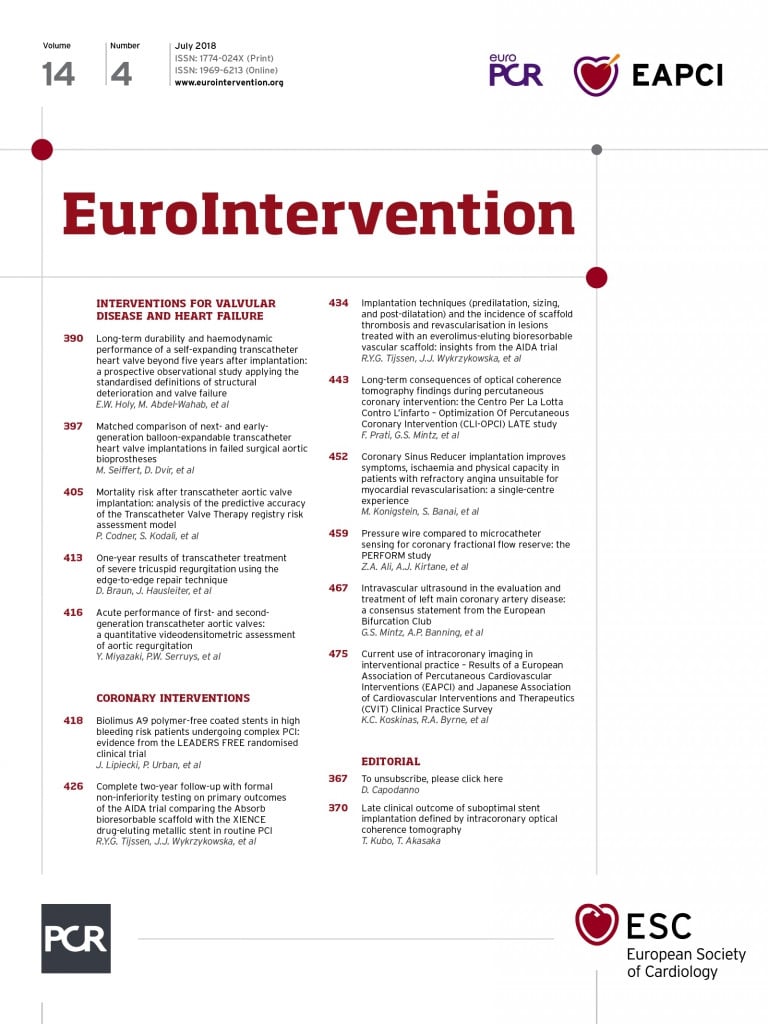

According to Wikipedia, spamming “is the use of electronic messaging systems to send an unsolicited message, especially advertising, as well as sending messages repeatedly on the same site”1. As many are aware, this phenomenon is named after Spam, a luncheon meat, by way of a Monty Python sketch2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of spam. Left: spiced ham (also known as SPAM), a brand of canned cooked meat, introduced in 1937. Right: spam-shaped word cloud of typical “academic spam” e-mail text.

Based on a hilarious but rigorous study, spamming of academic invitations “is common, repetitive, often irrelevant, and difficult to avoid or prevent”3. The relatively simple action of unsubscribing is possible but also almost meaningless: in the study, it reduced the frequency of the invitations by 39% after one month but by only 19% after one year. Jokes and studies apart, there is clearly a serious side to this matter. The goal of these daily spamming e-mails from questionable, “predatory” journals or websites is to mislead academics, particularly if they are at the start of their career, with the deliberate purpose of earning money through unethical practices4. Not only are these e-mails frustrating but they are also sometimes the gatekeeper for fraudulent phishing. Particularly in the “publish or perish” era (where pressure exists to publish academic research to sustain a career), the phenomenon of academic spamming is not only annoying but also worrisome. This is a call for action from competent authorities.