The concept of an open journal dates back almost two decades (2002, Budapest Open Access Initiative [BOAI], http://www.buda pestopenaccessinitiative.org) and has certainly changed the landscape of scientific publications. However, even today, this concept creates a certain confusion, disturbing the scientific serenity of editors, publishers, authors, readers and members of scientific societies alike. Why? What is the definition of an open journal? Is it strictly – and only – a new lucrative business model for publishers, or is it rather a generous attempt to offer the scientific community free access to science?

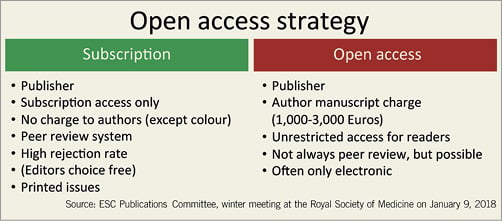

Recently, the 11 editors of the ESC Journal family met to reflect upon this issue. The topic was first introduced by Michael Alexander (ESC Head of Publications) at the bi-annual ESC Publications Committee meeting. Michael Alexander presented a comparative table of the salient features of an open journal versus those of a non-open journal (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparative table of the salient features of an open journal versus those of a non-open journal.

My first reaction after looking at this table was to try to position EuroIntervention somewhere between these two conceptions of a scientific publication. Editing, publishing and manufacturing a scientific journal is neither a free lunch nor a highly altruistic activity. Everything has a price in our society and the funding must come from somewhere. In 2004, when we decided to create the journal, the enthusiastic idealism of the founders led us to provide the journal (at that time 4 issues a year) for free, including the costs for the colour illustrations and downloading papers online. Let’s be frank, we should be both transparent and proud of the fact that this philanthropic management of the journal was most likely the result of the interaction of a few remarkable individuals, including Jean Marco (Founder and past Chair of EuroPCR), Marc Doncieux (Founder and CEO of Europa Group), Frederic Doncieux (Publisher at Europa Group) and others, who enabled this to happen.

The different open journal business models

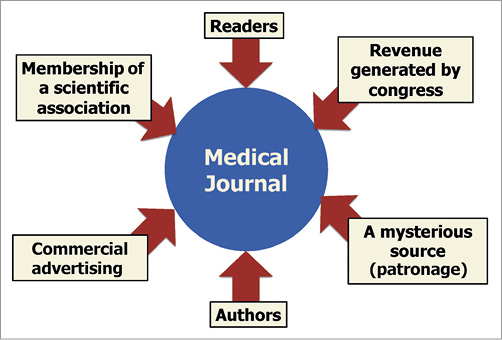

If you think about publishing costs, the necessary financial resources have to come from somewhere, whether it is the readers, the authors, commercial advertising, membership of a scientific association, revenue generated by congresses, or from a donor or foundation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Potential sources of revenue for medical journals.

EuroIntervention, the truly open access journal

According to the criteria formulated in the table of Michael Alexander (Figure 1), EuroIntervention is (in the most noble sense of the word) an open journal. The reader does not have to pay to access and download the papers published in the journal. The author does not have to pay to be published and there is no cost associated with publishing coloured static or dynamic illustrations. The libraries of scientific or academic institutions also have free access to the Journal. Of course, members of the association (EAPCI) get the content for free and, if a subscription exists to the journal, it is only for those who want to have a print issue, and have never attended the EuroPCR course. In other words, those who attend EuroPCR receive a year-long, free of charge subscription on top of their free access to the online content.

You may wonder, where does the funding come from?

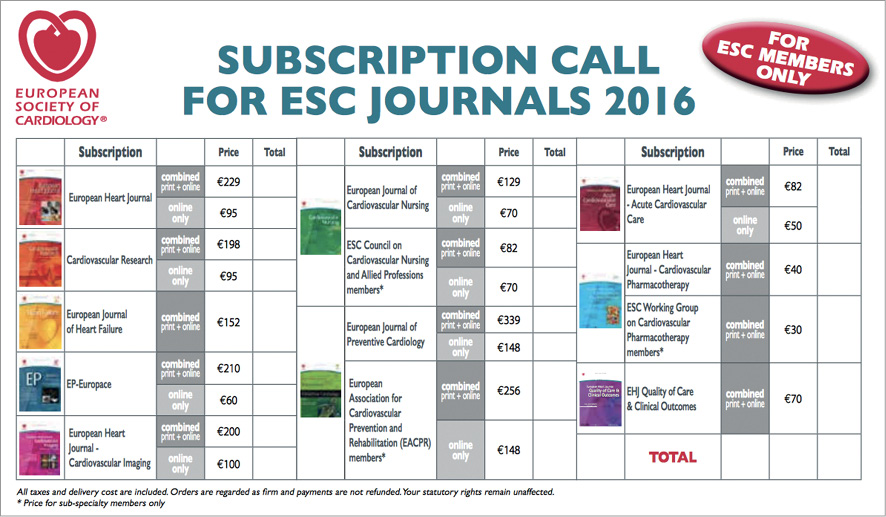

There are two sources of funding for EuroIntervention: commercial advertising and the EuroPCR course itself. In this respect, our journal’s financial strategies are at variance with those of the other journals in the ESC family in that these other journals request some (variable) financial contributions from their members (with the exception of the E-Journal of Cardiology Practice, which is published online only by the ESC) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Subscriptions for the ESC family of journals, 2016.

The “pay and publish” model – should the authors pay to be published?

The authors are the source for scientific information, stemming from their own work which is either subsidised by their academic milieu, or by national (e.g., Nederlandse Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek), European (e.g., EU2020) or international grants (e.g., the Leducq grant) that financially support the authors but request that they disseminate their scientific findings, making their work available to the scientific community at large.

Some journals have a first-class level of publication in the classic business model (free of charge, not including the costly coloured illustrations) and a second-class level for papers that are turned down for the first level, but nevertheless could be published in this “second-class level”, if the authors are willing to pay for publishing (the open journal business model). Apparently, the old academic dictum of “publish or perish” has evolved to become “pay and publish or perish”.

I have previously caught some young fellows submitting –without my agreement – a rejected paper for which the young fellow was offered (by the rejecting journal) a second-class level of publication in their open journal, of course at a cost (e.g., Open Heart, where the article publishing charge is 1,700 GBP, or JAHA with its $2,300 fee for direct manuscript submission).

Is there an honourable hybrid model?

The two conceptions of open journals outlined above represent two extremes. There is a very honourable hybrid version which is practised by the European Heart Journal. There, if the reader has a paper approved (after stringent peer review) and wants to disseminate the scientific work amongst the cardiology community, the European Heart Journal offers the author open access for their article to the community for a fee.

The dissemination of scientific data and the open access

Political authorities in the different European countries are also promoting free access to scientific data, not to mention the promotion of either big open data or of a public network. The hope is that the amount, transparency and accuracy of the circulating scientific data will thus be boosted and fostered. The President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker (Figure 4), is very outspoken and clear on this, declaring that “…research and innovation is changing rapidly. Digital technologies are making the conduct of science and innovation more collaborative, more international and more open to citizens. Europe must embrace these changes and reinforce its position as the leading continent for science, for new ideas, and for investing sustainably in the future. Open access can help overcome the barriers that innovative companies, in particular small and medium sized enterprises, face in accessing the results of research funded by the public purse. It has been estimated that switching to open access could result in annual savings of around £400 million for the UK, €133 m for the Netherlands and €80 m for Denmark.”1.

Figure 4. President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker.

As Michael Nielsen put it, “open science is ‘the idea that scientific knowledge of all kinds should be openly shared as early as is practical in the discovery process’. As a result, the way science is done in 2030 will look different from the way it is done now”2. It remains to be seen how the big multinational business companies (device and pharma industry) will react to this attempt to be transparent and open to the scientific communities.

A new model for EuroIntervention

EuroIntervention is now at a crossroads. The Journal is facing the economic reality of the publishing world and, in order to keep the same level of quality and to expand, the readers will be asked for a direct financial contribution.

Until now, EuroIntervention has been a real open journal that offered the scientific community free access to science, without asking authors or readers anything financial in return, but that time is coming to an end. In the coming months we will follow the path taken by the other Journals in the ESC family and start requiring a subscription.

In whatever we do, we assure our readers and authors who have made us what we are today, that we will not abuse your confidence; what we have chosen to do is required by the economic realities of the present, but it will not alter our original mission and we will continue to strive for the excellence that we all demand, exchanging the best scientific and clinical knowledge with all concerned, as we always have.