Abstract

Pharmacological treatment remains vital in the effective management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol-lowering therapies, such as statins, have consistently demonstrated robust efficacy in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. The introduction of ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors have further strengthened the effectiveness of LDL cholesterol management, particularly in patients who are statin intolerant or who remain at high risk despite maximal tolerated statin therapy. In addition to managing LDL cholesterol, addressing residual lipid risk by targeting elevated triglyceride and lipoprotein(a) levels and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels has emerged as a potentially important therapeutic consideration, as these are increasingly recognised as independent cardiovascular risk factors. Concurrently, inflammation is increasingly acknowledged as a significant contributor to atherogenesis and subsequent cardiovascular events. Clinical trials examining anti-inflammatory therapies, such as colchicine and interleukin-1β inhibitors (e.g., canakinumab), have demonstrated beneficial effects in reducing cardiovascular events independent of lipid modification. This narrative review provides an updated overview targeted specifically at physicians performing coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention. It summarises current evidence regarding established lipid-lowering therapies, emerging therapeutic approaches to address residual lipid risk, and the evolving role of anti-inflammatory interventions in the comprehensive management of ASCVD.

Lipid abnormalities are recognised as key modifiable risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), a chronic immune-inflammatory condition of the arterial wall that underpins the majority of cardiovascular (CV) events123.

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) has long been established as the primary target of lipid-lowering therapies. Statins remain the cornerstone of treatment, complemented by agents such as ezetimibe and bempedoic acid. More recently, novel therapies targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) have emerged, broadening the arsenal of options to lower LDL-C. Beyond managing LDL-C, the therapeutic landscape has expanded to address other lipid fractions, including lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], triglycerides (TG), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (HDL-C). These non-LDL-C targets reflect the growing understanding of the complex interplay of lipids in the pathogenesis of ASCVD. Additionally, evidence suggests that inflammatory biomarkers, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), may identify patients with an inflammatory residual risk phenotype of ASCVD, highlighting the potential role of novel anti-inflammatory therapies in reducing this residual risk4.

From a mechanical treatment perspective, it is noteworthy that the prognostic treatment effect of coronary artery bypass grafting, and to a lesser degree percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), in chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) appears to be primarily linked to the prevention of myocardial infarctions (MI)5. The treatment of inducible ischaemia has not been linked to a life-prolonging effect. Thus, the medical treatment mechanisms addressed here support the same outcome as invasive treatments, illustrating their additive potential and the importance of combining them at all times (both in primary and secondary prevention).

In this narrative review, we aim to provide an overview of pharmacological secondary prevention strategies that should be familiar to all physicians managing ASCVD, whilst also offering insights into contemporary and emerging therapies designed to address residual lipid and inflammatory risk in ASCVD management.

LDL-C-lowering therapies

Niacin, bile acid sequestrants, fibrates

Before statins became the primary lipid-lowering therapy, agents such as niacin (vitamin B3), bile acid sequestrants, and fibrates were used; however, they are no longer considered first-line options1.

Statins

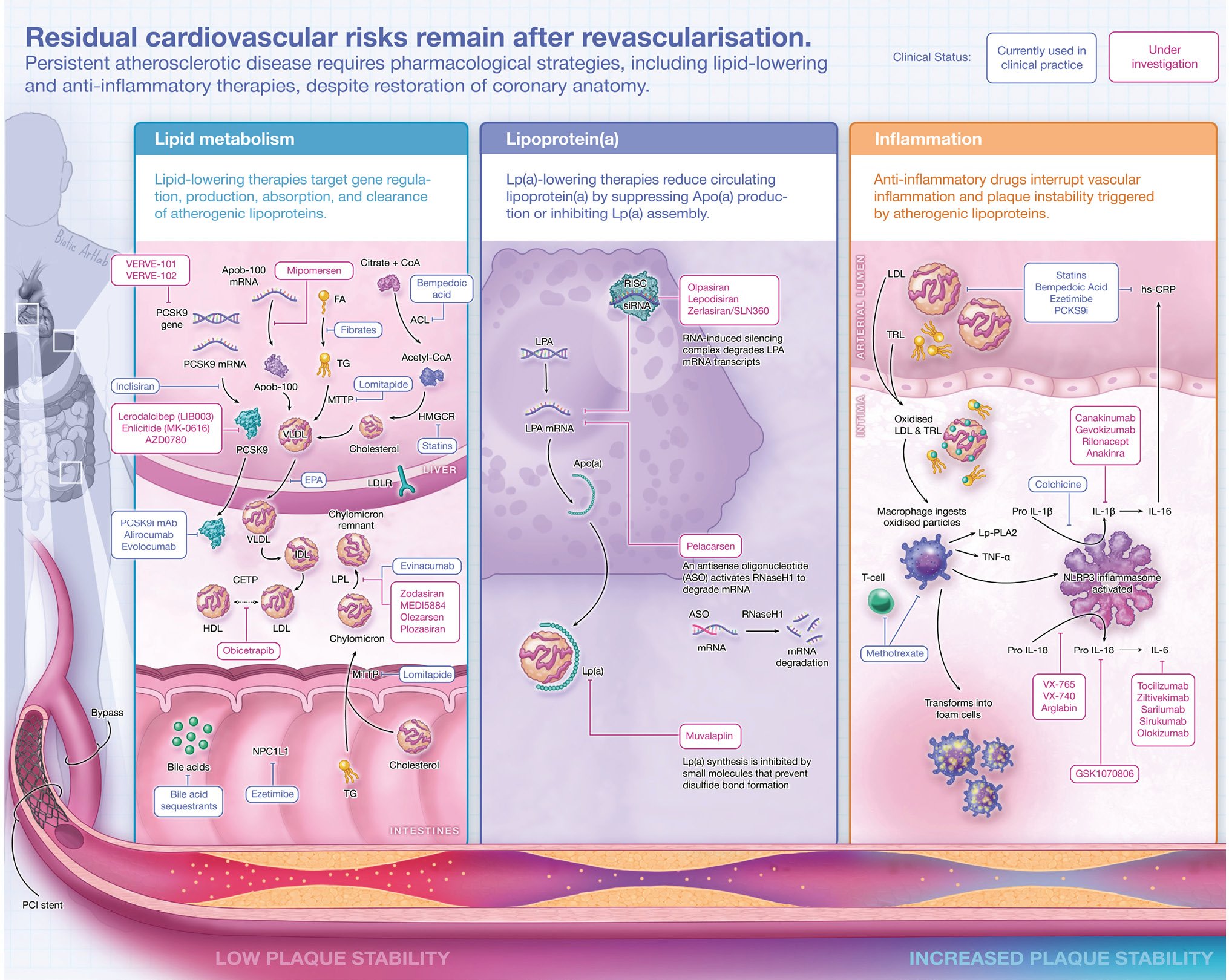

Statins are the most well-established agents in lipid-lowering therapy. Their primary mechanism of action involves the inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the intracellular pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis. This pathway uses acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), derived from acetate, as a substrate for cholesterol production (Central illustration A). This inhibition suppresses cholesterol synthesis and upregulates LDL receptor expression, leading to a reduction in circulating LDL-C levels6. The efficacy of statins has been demonstrated in primary and secondary prevention trials of coronary artery disease (CAD). For example, the 4S trial, involving 4,444 patients with hypercholesterolaemia and coronary heart disease, showed a 35% reduction in LDL-C and a 30% improvement in survival over a median follow-up of 5.4 years when comparing simvastatin with placebo7. Similarly, in the WOSCOPS trial, which enrolled 6,595 individuals with hypercholesterolaemia and no history of CAD, pravastatin reduced LDL-C by 26% and lowered cardiovascular events (defined as non-fatal MI or death from coronary heart disease) by 31% during a median follow-up of 4.9 years8. The efficacy and safety of statins have been consistently supported by numerous meta-analyses, solidifying their role as the first-line choice in lipid-lowering therapy9.

Central illustration. Pharmacological secondary prevention: targeting lipids and inflammation. Lipid-lowering therapies (A, B) and anti-inflammatory therapies (C). Created with BioRender.com. ACL: ATP citrate lyase; ApoA: apolipoprotein A; ApoB-100: apolipoprotein B-100; ANGPTL3-i: angiopoietin-like protein 3 inhibitor; ASO: antisense oligonucleotide; CETP: cholesteryl ester transfer protein; CETPi: CETP inhibitor; CoA: coenzyme A; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; FA: fatty acids; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HMGCR: 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase; IDL: intermediate-density lipoprotein; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1 beta; IL-6: interleukin-6; IL-16: interleukin-16; IL-18: interleukin-18; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LDLR: low-density lipoprotein receptor; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); Lp-PLA2: lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2; LPL: lipoprotein lipase; mAb: monoclonal antibody; mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid; MTTP: microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; NLRP3: nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; NPC1L1: Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; PPAR-α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; RISC: RNA-induced silencing complex; RNAi: RNA interference; RNaseH1: ribonuclease H1; siRNA: small interfering ribonucleic acid; TG: triglyceride; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha; TRL: triglyceride-rich lipoprotein; VLDL: very low-density lipoprotein

Ezetimibe, bempedoic acid

Ezetimibe lowers serum LDL-C by blocking the Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) protein in the small intestine, thereby inhibiting the absorption of both dietary and biliary cholesterol (Central illustration A)10. Its efficacy for improving cardiovascular outcomes was demonstrated in the IMPROVE-IT study, which showed that combining it with simvastatin 40 mg in patients with recent acute coronary syndromes (ACS) reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at 7 years (hazard ratio [HR] 0.936, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.89-0.99; p=0.016)11. Ezetimibe is also useful in statin-intolerant patients, with a meta-analysis reporting that ezetimibe monotherapy reduces LDL-C by 15-20%12.

Another promising option for statin-intolerant patients is bempedoic acid. This adenosine triphosphate (ATP) citrate lyase (ACL) inhibitor targets cholesterol synthesis upstream of the pathway inhibited by statins (Central illustration A), thereby lowering hepatic cholesterol synthesis, increasing LDL receptor expression, and reducing LDL-C levels13. The CLEAR Outcomes trial, which enrolled 13,970 statin-intolerant patients at high cardiovascular risk, showed that bempedoic acid (180 mg daily) significantly reduced the incidence of MACE compared to placebo (11.7% vs 13.3%; HR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.79-0.96; p=0.004)14. These results highlight the importance of ezetimibe and bempedoic acid as alternatives for patients who cannot tolerate statins.

PCSK9 inhibitors (currently used in clinical practice)

Monoclonal antibody

In recent years, increasing attention has been directed towards inhibitors of PCSK9 – a protein which binds to low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDLRs) on hepatocyte surfaces, promoting their lysosomal degradation (Central illustration A). This process prevents the recycling of LDLRs to the cell surface, thereby reducing receptor-mediated clearance of LDL-C from the bloodstream; it follows that PCSK9 inhibitors restore LDLR recycling, leading to a reduction in serum LDL-C levels of 50-65%15.

The PCSK9 inhibitors currently available in clinical practice include alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha), which are monoclonal antibodies (mAb) targeting PCSK9, as well as inclisiran (Leqvio), a small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) that prevents the translation of PCSK9.

Two major randomised outcomes trials have demonstrated the efficacy of mAb PCSK9 inhibitors in significantly lowering the risk of MACE. The FOURIER trial, which included 27,564 patients with stable ASCVD who were followed for a median of 2.2 years, reported a 59% reduction in LDL-C levels with evolocumab compared to placebo: LDL-C levels decreased from a median baseline of 92 mg/dL (2.4 mmol/L) to 30 mg/dL (0.78 mmol/L; p<0.001). Notably, evolocumab significantly reduced the risk of MACE (9.8% [1,344 patients] vs 11.3% [1,563 patients]; HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.79-0.92; p<0.001)16. The ODYSSEY Outcomes trial included 18,924 patients who experienced an ACS 1 to 12 months before enrolment, with a median follow-up of 2.8 years. Alirocumab therapy achieved a median 1-month LDL-C level of 40 mg/dL and significantly reduced the risk of MACE (9.5% [903 patients] vs 11.1% [1,052 patients]; HR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.78-0.93; p<0.001)17. Extended follow-up of both trials showed sustained reductions in MACE without safety concerns, further establishing their effectiveness1819.

More recently, the VESALIUS-CV trial demonstrated that evolocumab reduced 3-point MACE (CAD, MI, or ischaemic stroke) from 8.0% (443 patients) to 6.2% (336 patients; HR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.65-0.86; p<0.001), and lowered 4-point MACE (3-point MACE plus ischaemia-driven revascularisation) from 16.2% (907 patients) to 13.4% (747 patients; HR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.73-0.89; p<0.001) in patients without prior myocardial infarction or stroke, with no safety concerns during 4.6 years of follow-up20.

Small interfering ribonucleic acid

Inclisiran, an siRNA, is a next-generation PCSK9 inhibitor. siRNA silences complementary target messenger ribonucleic acids (mRNAs) in a sequence-specific manner through effector ribonucleic acid (RNA)-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) (Central illustration A)21. Inclisiran is incorporated into these RISCs within hepatocytes where it degrades PCSK9 mRNA. This reduction in PCSK9 levels prevents LDLR degradation, thereby increasing LDLR availability, enhancing LDL-C clearance, and ultimately lowering blood LDL-C levels22.

Inclisiran is administered initially (day 1), at 3 months, and then every 6 months, offering the advantage of infrequent dosing. Its efficacy has been confirmed in the ORION-923, ORION-1024, and ORION-11 trials24, which consistently demonstrated significant reductions in LDL-C levels of 49.7%, 52.3%, and 50% at 17-month follow-up compared to placebo in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (HeFH), established ASCVD, and ASCVD risk equivalents, respectively. Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of inclisiran as an effective and well-tolerated therapeutic option, particularly for patients requiring intensive, long-term LDL-C management. Large-scale cardiovascular outcomes trials such as ORION-4 (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03705234), VICTORION-2 PREVENT (NCT05030428), and VICTORION-1 PREVENT (NCT05739383) are anticipated to conclude in 2026, 2027, and 2029, respectively, with their findings highly anticipated to further elucidate the potential of inclisiran in mitigating cardiovascular risk. Complementing these studies, the V-PLAQUE trial (NCT05360446) is currently evaluating inclisiran’s effect on coronary plaque burden by coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography25.

PCSK9 inhibitors (currently under clinical investigation)

Antisense oligonucleotide

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are nucleic acid polymers (deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA] or RNA) composed of a short strand of nucleotide which function by binding to the complementary (sense) strand on the target mRNA, inactivating it26. Several PCSK9-targeting ASOs, including BMS-84421, SPC5001, CiVi007, and AZD8233, have been developed and evaluated for their lipid-lowering potential. Notably, the oral drug AZD8233 progressed to a Phase 2b clinical trial, which showed that a monthly dose of AZD8233 60 mg was safe and generally well tolerated, and resulted in a statistically significant 62.3% reduction in LDL-C at 28 weeks compared to placebo, meeting the primary efficacy endpoint27. These findings, however, did not meet the prespecified efficacy criteria, and AstraZeneca elected not to advance AZD8233 into Phase 3 development for hypercholesterolaemia. Consequently, no PCSK9-targeting ASOs have yet reached the clinical market.

Macrocyclic peptide oral PCSK9 inhibitor

AZD0780 is a novel oral small molecule PCSK9 inhibitor (Central illustration A) assessed in the Phase 2 PURSUIT trial of 426 statin-treated patients with hypercholesterolaemia. It achieved dose-dependent LDL-C reductions of up to 50.7% at 12 weeks and was well tolerated, indicating its potential as an effective and convenient oral option28. Similarly, Enlicitide (MK-0616) is an investigational oral macrocyclic peptide that binds to PCSK9 with an affinity similar to that of mAb (Central illustration A)29. In a Phase 2b clinical trial of 380 patients at risk for ASCVD, participants were randomly assigned (1:1:1:1:1) to receive MK-0616 (6, 12, 18, or 30 mg once daily) or placebo. MK-0616 elicited dose-dependent, statistically significant, placebo-adjusted reductions in LDL-C of up to 60.9% at week 8 (p<0.001) and was well tolerated during the 8-week treatment period and additional 8-week follow-up30. More recently, the Phase 3 CORALreef Lipids trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05952856) evaluated enlicitide over 52 weeks in 2,909 adults with elevated LDL-C who either had ASCVD or were at intermediate to high risk of a major ASCVD event. Participants receiving enlicitide 20 mg once daily showed placebo-adjusted reductions in LDL-C of 55.8% at week 24 and 47.6% at week 52 (both p<0.001), with rates of adverse events and treatment discontinuation similar to those of placebo31. Based on these findings, a Phase 3 trial, the CORALreef Outcomes trial (NCT06008756), is currently underway in 14,450 patients at high cardiovascular risk to compare MACE between a 20 mg dose of MK-0616 and placebo. The study is anticipated to report in 2029.

Adnectin

Adnectins are engineered protein therapeutics like mAb that bind and inhibit PCSK9, thereby reducing active levels (Central illustration A). They are derived from the 10th type III domain of human fibronectin (10Fn3), with variable loops engineered to enable high affinity and specific binding to therapeutic targets3233. Among the most advanced drugs in this class is lerodalcibep (LIB003), which combines an adnectin with human serum albumin to extend its half-life. In a Phase 2 dose-ranging trial, a 300 mg monthly subcutaneous injection of LIB003 resulted in a mean placebo-adjusted LDL-C reduction of 77.3%34. Over 52 weeks, this 300 mg dose was well tolerated, and led to mean LDL-C reductions of over 60%34. In the Phase 3 trial LIBerate-HoFH, conducted in patients with genetically confirmed homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (HoFH), LIB003 reduced LDL-C levels by 9.26% after 24 weeks, compared with an 11.0% reduction with evolocumab, with the difference not statistically significant35. The LIBerate-H2H trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04790513) aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of LIB003 300 mg, evolocumab 420 mg, and alirocumab 150 mg in patients at high risk for CVD. While enrolment was completed in September 2022, no results have been reported to date, and consequently, LIB003 has not yet reached the clinical market.

Vaccine/gene editing

Single-treatment approaches that could potentially provide lifelong reductions in LDL-C are being investigated, with a focus on vaccines and gene-editing technologies.

The anti-PCSK9 vaccines AT04A and AT06A have progressed to clinical trials. In a Phase 1 trial involving 72 healthy subjects with a mean fasting LDL-C level of 117.1 mg/dL at baseline, AT04A resulted in a significant mean LDL-C reduction of 7.2% compared to placebo (95% CI: –10.4 to –3.9; p<0.0001), with no significant reductions seen with AT06A in the same trial36. No recent clinical trial updates have been reported for these vaccine candidates.

Gene editing is a cutting-edge biotechnology with the potential for lifelong therapeutic effects by altering DNA itself. The development of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) technology has greatly advanced this field, enabling targeted treatment of genetic diseases. Non-clinical and clinical studies for hypercholesterolaemia treatment are underway37. VERVE-101, an investigational in vivo CRISPR base-editing therapy, is designed to permanently deactivate the PCSK9 gene, thereby reducing hepatic PCSK9 production and LDL-C levels (Central illustration A). In a preclinical trial involving 10 cynomolgus monkeys, VERVE-101 reduced blood PCSK9 levels by 83% and LDL-C by 69%, with effects lasting up to 476 days38. In humans, the Phase 1b Heart-1 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05398029) enrolled ten patients with high cardiovascular risk who received VERVE-101 across four dose cohorts (0.1-0.6 mg/kg). Interim results have been presented and showed LDL-C reductions of 39% and 48% in two participants receiving 0.45 mg/kg and a reduction of 55% in the participant taking 0.6 mg/kg, with this latter reduction sustained for 180 days. PCSK9 levels decreased by up to 84%39. Further development of VERVE-101 was halted in April 2024 after one participant experienced transient elevations in hepatic transaminases and thrombocytopaenia, adverse effects attributed to the formulation’s lipid-nanoparticle (LNP) coating.

To address these safety signals, a N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc)-targeted LNP version, VERVE-102, is being investigated in the Heart-2 Phase Ib trial. Fourteen patients with HeFH and/or premature CAD received single doses of 0.3, 0.45, or 0.6 mg/kg and have completed at least 28 days of follow-up. VERVE-102 produced dose-dependent declines in PCSK9 and LDL-C; in the 0.6 mg/kg cohort, the mean and maximal LDL-C reductions were 53% and 69%, respectively, mirroring reductions in total hepatic RNA editing. The therapy was well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities or serious cardiovascular events, and no clinically significant changes in liver enzymes or platelet counts40.

While gene editing holds huge potential, challenges such as ethical concerns and off-target effects require careful evaluation of its safety and efficacy. Nonetheless, it represents a promising frontier in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. Current LDL-C-lowering therapies targeting PCSK9 are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Current LDL cholesterol-lowering therapies targeting PCSK9.

| Therapeutic class | Drug name | Trade name | Year of introduction to clinical trials | Status for approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibody | Alirocumab | Praluent | 2009 | Approved by FDA, EMA, and NICE |

| Evolocumab | Repatha | 2010 | Approved by FDA, EMA, and NICE | |

| Bococizumab | - | 2013 | Phase 3 was discontinued because of antidrug antibody attenuation of efficacy and lack of strong evidence in reducing major cardiovascular events | |

| Frovocimab | - | 2011 | Terminated at Phase 2 | |

| Small interfering RNA | Inclisiran | Leqvio | 2011 | Approved by FDA, EMA, and NICE |

| Antisense oligonucleotide | BMS-844421 | - | 2010 | Terminated at phase 1 |

| SPC5001 | - | 2011 | Terminated at phase 1 | |

| CiVi007 | - | 2018 | Phase 2a trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04164888) was completed but not reported | |

| AZD8233 (ION-863633) | - | 2018 | Terminated at Phase 2 | |

| Mimetic peptide | Enlicitide (MK-0616) | - | 2022 | Phase 3 trial (NCT06008756) is ongoing |

| AZD0780 | - | 2024 | Phase 2 trial (NCT06173570)28 was reported in 2025 | |

| Adnectin | BMS-962476 | - | 2012 | Phase 1 No update since 2013 |

| Lerodalcibep (LIB003) | - | 2018 | Phase 3 trial (NCT04790513) was completed but no results have been reported | |

| Anticalin fusion proteins | DS-9001a | - | 2018 | Phase 1 No update since 2013 |

| Vaccine | AFFITOPE peptide AT04A | - | 2015 | Phase 1 No update since 2021 |

| AFFITOPE peptide AT06A | - | 2015 | Phase 1 No update since 2021 | |

| Capsid-VLP PCSK9 | - | 2022 | Preclinical | |

| Gene editing | LNP carrying seventh-generation ABE (7.10) messenger RNA and CRISPR guide RNA | - | 2021 | Preclinical |

| LNP carrying eighth-generation ABE (8.8) messenger RNA and CRISPR guide RNA (VERVE-101) (VERVE-102) | - | 2023 | Preclinical | |

| ABE: adenine base editor; CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LNP: lipid nanoparticle; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; RNA: ribonucleic acid; VLP: virus-like particle | ||||

ANGPTL3 inhibitor

ANGPTL3 is another prominent target for LDL-C-lowering therapies following PCSK9 inhibition. ANGPTL3 is a protein, mainly produced and secreted by the liver, that regulates lipid metabolism by inhibiting lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and endothelial lipase (EL) (Central illustration A). ANGPTL3 inhibitors (ANGPTL3-i) restore the activity of LPL and EL, which promotes the processing and clearance of very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), leading to reductions in circulating TG and LDL-C41. Currently, the only ANGPTL3-i available for clinical use is the mAb evinacumab. In the Phase 3 ELIPSE HoFH trial, conducted in patients with HoFH, evinacumab resulted in a 49% reduction in LDL-C relative to placebo (95% CI: 33.1-65.0; p<0.001) at 24 weeks42. Based on these results, it has been approved for clinical use in patients aged 12 years or older with HoFH. Evinacumab has also shown efficacy in reducing LDL-C and TG levels in other populations. In a Phase 1 trial43, it demonstrated effects in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia, while in a Phase 2 trial, it reduced LDL-C and TG levels in patients with refractory hypercholesterolaemia44. These findings suggest a broader therapeutic potential for ANGPTL3 inhibitors beyond HoFH.

Recent efforts have extended CRISPR-based approaches to ANGPTL3 as well. In a first-in-human, ascending-dose Phase 1 trial, a single intravenous dose of CTX310 led to dose-dependent reductions in circulating ANGPTL3 levels of up to nearly 80%. These findings indicate that permanent inactivation of ANGPTL3 may represent a future strategy for lipid lowering45.

Other therapies (ApoB inhibitor, MTTP inhibitor)

Other clinically approved therapies to reduce LDL-C include mipomersen and lomitapide, although their clinical roles differ significantly. Mipomersen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting ApoB-100 mRNA, is now rarely used clinically because of severe side effects, including injection site reactions, flu-like symptoms, and significant hepatotoxicity. In contrast, lomitapide − an MTTP inhibitor − remains approved and is actively used for the treatment of HoFH, despite causing modest increases in liver fat that typically stabilise over time4647. An overview of novel LDL-C-lowering therapies along with their clinical approval status is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Novel LDL-C-lowering therapies with their clinical approval status.

| Target | Therapeutic class | Drug name | Trade name | Delivery method and dosage | Indications for usage | Status for approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSK9 | Anti-PCSK9 human monoclonal antibody | Alirocumab | Praluent | Subcutaneous injection: 75 mg biweekly or 300 mg monthly | ASCVD requiring additional LDL cholesterol reduction; primary hypercholesterolaemia; adjunct for homozygous FH | FDA, EMA, NICE |

| PCSK9 | Anti-PCSK9 human monoclonal antibody | Evolocumab | Repatha | Subcutaneous injection: 140 mg biweekly or 420 mg monthly | ASCVD with major cardiac event risk; primary hyperlipidaemia; adjunct for homozygous FH | FDA, EMA, NICE |

| PCSK9 | Small interfering RNA | Inclisiran | Leqvio | Subcutaneous injection: 284 mg initial dose, follow-up at 3 months, then every 6 months | ASCVD requiring LDL cholesterol reduction; adjunct to diet and statin therapy in heterozygous FH | FDA, EMA, NICE |

| ANGPTL3 | Anti-ANGPTL3 human monoclonal antibody | Evinacumab | Evkeeza | Intravenous infusion: 15 mg/kg monthly | Adjunct to LDL cholesterol-lowering therapies in individuals aged 12+ with homozygous FH | FDA, EMA |

| ApoB | Antisense oligonucleotide | Mipomersen | Kynamro | Subcutaneous injection: 200 mg weekly | As a supplementary therapy alongside diet modification and lipid-reducing medications in patients with homozygous FH | FDA (with Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies programme) |

| MTTP | Small molecular inhibitor of MTTP | Lomitapide | Juxtapid (US and Canada), Lojuxta (EU) | Oral capsule: 5 mg daily, titrate to max 60 mg/day | As a supplementary therapy alongside diet modification and lipid-reducing medications in patients with homozygous FH | FDA, EMA |

| ANGPTL3: angiopoietin-like 3; ApoB: apolipoprotein B; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; FH: familial hypercholesterolaemia; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; MTTP: microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 | ||||||

Lp(a)-lowering therapy

Recently, Lp(a) has emerged as an important focus for cardiovascular research. Structurally, it is a small LDL particle, <30 nm in diameter, which allows it to cross the endothelial barrier freely, similar to LDL-C. Upon crossing, it can directly or indirectly interact with local tissues, promoting inflammation and atherogenesis2. Unlike most dyslipidaemias, Lp(a) levels are determined by genetics in more than 90% of patients and are minimally influenced by lifestyle modifications such as diet or exercise, and therefore, numerous clinical guidelines recommend having an Lp(a) measurement at least once in a lifetime248.

Although there is no universally established threshold for elevated Lp(a), prior studies indicate that cardiovascular disease risk increases significantly at levels above approximately 30 mg/dL or 50 mg/dL. In the Copenhagen City Heart Study, individuals with Lp(a) levels exceeding 30 mg/dL had a significantly higher risk of MI. Specifically, the adjusted HR was 1.6 (95% CI: 1.1-2.2) for those with levels between 30 mg/dL and 76 mg/dL and 1.9 (95% CI: 1.2-3.0) for levels between 77 mg/dL and 117 mg/dL, compared to individuals with levels below 5 mg/dL49. A meta-analysis of 36 prospective studies, encompassing 126,634 patients with baseline Lp(a) measurements and long-term clinical outcomes, found a significant increase in the risk of MI for Lp(a) levels above 24 mg/dL50. More recently, a large analysis from the UK Biobank, including 460,506 participants, demonstrated a clear linear relationship between Lp(a) concentration and ASCVD risk51. Additionally, a large population study involving 532,359 individuals estimated that approximately one in five individuals has an Lp(a) level over 50 mg/dL52.

Currently, there are no drugs specifically approved for lowering Lp(a); however, some existing therapies have demonstrated a bystander effect in reducing Lp(a). For instance, niacin has shown an up to 20% reduction in Lp(a) levels53, while PCSK9 inhibitors (alirocumab and evolocumab) can reduce Lp(a) levels by up to 30%, with these reductions contributing significantly to the observed decrease in MACE among patients with high baseline Lp(a)1754.

siRNA, ASOs, small molecule inhibitors of Lp(a)

Although no therapies specifically targeting Lp(a) have been approved to date, several drugs, including ASOs, siRNAs, and small molecules, are currently in Phase 2 and Phase 3 trials (Table 3, Central illustration B). In the ALPACAR-360 trial, zerlasiran − an siRNA targeting Lp(a) − significantly reduced Lp(a) levels among 178 patients with ASCVD. Compared with the pooled placebo group, the least-squares mean time-averaged percentage changes in Lp(a) concentration from baseline to week 36 were –85.6% (95% CI: –90.9% to –80.3%), –82.8% (95% CI: –88.2% to –77.4%), and –81.3% (95% CI: –86.7% to –76.0%) for the three dosing groups, 450 mg every 24 weeks, 300 mg every 16 weeks, and 300 mg every 24 weeks, respectively55. In the KRAKEN trial, oral muvalaplin, a small molecule that reduces Lp(a) synthesis by preventing the disulfide bond formation between apolipoprotein A (ApoA) and Lp(a)56, was evaluated in 233 patients with an Lp(a) ≥175 nmol/L and ASCVD, diabetes, or heart failure. Muvalaplin showed placebo-adjusted reductions in Lp(a) of 47.6% (95% CI: 35.1-57.7%), 81.7% (95% CI: 78.1-84.6%), and 85.8% (95% CI: 83.1-88.0%) for the 10 mg/day, 60 mg/day, and 240 mg/day dosages, respectively57. Results of the Phase 2 ALPACA trial, reported in March 2025, further reinforced the therapeutic promise of Lp(a) silencing. In 320 adults with a median baseline Lp(a) of 254 nmol/L, lepodisiran achieved placebo-adjusted, time-averaged Lp(a) reductions from day 60 to day 180 of 41% (16 mg), 75% (96 mg) and 94% (pooled 400 mg groups). The effects persisted up to one year, and no treatment-related serious adverse events were observed58. Ongoing and recent clinical trials are listed in Table 3 and aim to establish the clinical efficacy of Lp(a)-targeting therapies, and their results are eagerly awaited.

Table 3. Clinical trials for novel Lp(a)-lowering therapies.

| Drug | Trial | Phase | Mechanism | Study population | N | Estimated completion date or results | Delivery method | ClinicalTrials.gov or article reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelacarsen | Lp(a)HORIZON | 3 | Antiapo(a) ASO | High Lp(a) (≥70 mg/dL) and established ASCVD | 8,323 | May 2025 | Subcutaneous injection | NCT04023552 ongoing |

| Pelacarsen | Lp(a)FRONTIERS CAVS | 2 | Antiapo(a) ASO | High Lp(a) (≥175 nmol/L), mild-moderate AS and optimally treated cardiovascular risk factors | 502 | December 2028 | Subcutaneous injection | NCT05646381 ongoing |

| Olpasiran | OCEAN(a) | 3 | Antiapo(a) siRNA | High Lp(a) (≥200 nmol/L) and established ASCVD | 7,000 | December 2026 | Subcutaneous injection | NCT05581303 ongoing |

| Zerlasiran/ SLN360 | ALPACAR-360 | 2 | Antiapo(a) siRNA | High Lp(a) (≥125 nmol/L) at high risk of ASCVD events with BMI 18-32 kg/m2 | 172 | Zerlasiran reduced time-averaged Lp(a) concentration by more than 80% for 36 weeks and was well tolerated | Subcutaneous injection | 55 |

| Lepodisiran | ACCLAIM-Lp(a) | 3 | Antiapo(a) siRNA | High Lp(a) (≥175 nmol/L) with any of the following: (1) established ASCVD with a previous event; (2) aged >55 years with established ASCVD; (3) FH; (4) a combination of risk factors, and at high risk of a first event | 12,500 | March 2029 | Subcutaneous injection | NCT06292013 ongoing |

| Lepodisiran | ALPACA | 2 | Antiapo(a) siRNA | High Lp(a) (≥175 nmol/L) on stable lipid-lowering or endocrine drugs/supplements with BMI 18.5-40 kg/m2 | 254 | Lepodisiran reduced Lp(a) by 41–94% vs placebo from day 60 to day 180 and was well tolerated | Subcutaneous injection | 58 |

| Muvalaplin | KRAKEN | 2 | Oral small molecule inhibitor of Lp(a) formation | Lp(a) ≥175 nmol/L with ASCVD, DM, or FH | 233 | Muvalaplin reduced Lp(a) by 70-86% measured using intact Lp(a) and apolipoprotein(a)-based assays and was well tolerated | Oral | 57 |

| Antiapo(a): antiapolipoprotein(a); AS: aortic stenosis; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; ASO: antisense oligonucleotide; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; FH: familial hypercholesterolaemia; Lp: lipoprotein; MI: myocardial infarction; siRNA: small interfering ribonucleic acid | ||||||||

Triglyceride-lowering therapy

Elevated TG levels have garnered increasing attention as a contributor to the residual risk of ASCVD.

Fibrates

Fibrates primarily act by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPAR-α), leading to the upregulation of LPL and enhanced catabolism of TG-rich lipoproteins, which effectively lowers TG and modestly raises HDL-C levels (Central illustration A)59.

Early landmark trials, such as the HHS trial60 and the VA-HIT trial61, demonstrated significant reductions in cardiovascular events with gemfibrozil, particularly in patients with low HDL-C and moderately elevated TG levels. Notably, these trials were conducted before the efficacy of statin therapy was established, and neither trial included participants taking statins. Subsequent studies yielded mixed results, with the FIELD62 and ACCORD Lipid trials63 failing to demonstrate statistically significant cardiovascular benefits of fenofibrate on the primary endpoints in the overall population. Nonetheless, subgroup analyses suggested potential benefits in patients with elevated TG and low HDL-C levels, indicating that fibrates might be most effective in specific lipid profiles. More recently, pemafibrate − a selective PPAR-α modulator − failed to significantly reduce MACE in the PROMINENT trial of 10,497 patients with type 2 diabetes and high TG levels over a median 3.4-year follow-up64. Consequently, while fibrates may benefit certain patient subsets – particularly those with high TG and low HDL-C levels – their role in contemporary lipid management remains questionable.

High-dose omega-3 fatty acids

High-dose omega-3 fatty acids, particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), have emerged as another strategy for addressing residual cardiovascular risk. The JELIS trial demonstrated that 1,800 mg/day of EPA combined with statins reduced coronary events by 19%, with greater benefits observed in patients with TG ≥150 mg/dL65. The REDUCE-IT trial enrolled 8,179 patients on statins with TG levels between 135 mg/dL and 499 mg/dL and further established the role of high-purity EPA. Treatment with 4 g/day of icosapent ethyl resulted in respective reductions in MACE and cardiovascular deaths of 25% and 20%66. Conversely, trials evaluating combinations of EPA and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), such as the STRENGTH67 and OMEMI68 trials, have not demonstrated a cardiovascular benefit. Moreover, a meta-analysis of randomised trials reported an approximately 25% increased risk of atrial fibrillation with omega-3 supplementation, particularly at doses greater than 1 g/day69. From the perspective of “pharmacological revascularisation”, the EVAPORATE trial showed that treatment with icosapent ethyl (4 g/day) led to only a 17% increase in low-attenuation plaque volume over 18 months, compared to a 109% increase in the placebo group (p=0.006). These results highlight EPA’s potential to modulate plaque progression and support its role in enhancing vascular health70. Of note, the benefit of EPA was independent of baseline TG levels, with the change in TG levels also not correlating to the reduction in MACE. Hence, the benefit of EPA was not considered to relate to the modest change in TG levels but rather to reflect a direct beneficial effect of EPA following its incorporation into the cellular membranes of various cells. Examples of approved drugs to lower TG levels are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Examples of approved drugs for TG-lowering therapies.

| Therapeutic class | Drug name | Mechanism of function | Trial | Target populations | N | Outcomes | Delivery method and dosage | Adverse events | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrates | Gemfibrozil | Activates PPAR-α | HHS (Helsinki Heart Study) | Asymptomatic males (40-55 years) with primary dyslipidaemia (non-HDL-C ≥200/dL [5.2 mmol/L] in two consecutive pretreatment measurements) | 4,081 | Risk of CV events ↓ | 600 mg twice daily/1,200 mg per day | Dyspepsia | 60 |

| Gemfibrozil | Activates PPAR-α | VA-HIT (Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial) | Males with CAD, an HDL-C ≤40 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) and an LDL-C ≤140 mg/dL (3.6 mmol/L) | 2,531 | Risk of CV events ↓ | 600 mg twice daily/1,200mg per day | Dyspepsia | 61 | |

| Fenofibrate | Activates PPAR-α | FIELD (Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes) | Participants aged 50-75 years, with type 2 DM, and not taking statin therapy at study entry | 9,795 | No significant reduction in primary outcome of coronary events | 200 mg once daily | Risk of pancreatitis, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis | 62 | |

| Fenofibrate | Activates PPAR-α | ACCORD Lipid (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) | Patients with type 2 DM who were being treated with open-label simvastatin to receive either masked fenofibrate or placebo | 5,518 | Risk of total cardiovascular disease events ↓ | 200 mg once daily | Risk of pancreatitis, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis | 63 | |

| Pemafibrate | Activates PPAR-α | PROMINENT (Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes by Reducing Triglycerides in Patients with Diabetes) | Patients with type 2 DM, a fasting TG of 200-499 mg/dL, and an HDL-C ≤40 mg/dL | 10,497 | No significant reduction in major cardiovascular events | 0.2 mg tablets twice daily | Venous thromboembolism | 64 | |

| High-dose omega-3 fatty acids | Eicosapentaenoic acid | The biological functions of EPA include reduction of platelet aggregation, vasodilation, antiproliferation, plaque-stabilisation and reduction in lipid action | JELIS (Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study) | Patients with a total cholesterol ≥6.5 mmol/L | 18,645 | Coronary events 19% ↓ | 1,800 mg/day | Nausea, diarrhoea, epigastric discomfort, itching | 65 |

| Icosapent ethyl | Highly purified and stable EPA ethyl ester shown to lower triglyceride levels | REDUCE-IT (Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl – Intervention Trial) | Patients with established CVD or with DM and other risk factors, who had been receiving statin therapy and who had a fasting TG level of 135-499 mg/dL (1.52-5.63 mmol/L) and a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of 41-100 mg/dL (1.06-2.59 mmol/L) | 8,179 | MACE 25% ↓ Cardiovascular death 20% ↓ | 4 g/day | Bleeding | 66 | |

| CAD: coronary artery disease; CV: cardiovascular; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; PPAR-α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; TG: triglyceride | |||||||||

Apolipoprotein C-III, ANGPTL3 inhibitor

RNA-targeting therapies targeting apolipoprotein C-III (APOC3) and ANGPTL3 are currently under investigation for treating mixed hyperlipidaemia, familial chylomicronaemia syndrome (FCS), and severe hypertriglyceridaemia. A brief summary of drugs undergoing clinical trials for lowering TG, along with the promising results from recent trials, is shown in Table 5. Olezarsen, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting APOC3 (Central illustration A), was shown to significantly reduce TG levels compared to placebo in the Phase 2b Bridge–TIMI 73a trial of patients with moderate (TG levels 150-499 mg/dL) or severe hypertriglyceridaemia (TG ≥500 mg/dL)71, and in the Phase 3 BALANCE trial of patients with FCS and fasting TG >880 mg/dL72. Another agent targeting APOC3 is plozasiran, an siRNA (Central illustration A) which, likewise, has shown significant reductions in TG levels compared to placebo in the Phase 2b SHASTA-2 trial of patients with FCS and severe hypertriglyceridaemia (fasting TG levels 500-4,000 mg/dL)73, the Phase 3 PALISADE trial of patients with FCS (TG ≥880 mg/dL or genetically confirmed)74, and the Phase 2b MUIR trial, of patients with mixed hyperlipidaemia (TG 150-499 mg/dL and LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100 mg/dL)75.

Therapies targeting ANGPTL3 have also shown promising results. Zodasiran, an RNA interference (RNAi) therapy directed against ANGPTL3 expression in the liver (Central illustration A), was examined in the Phase 2b ARCHES-2 trial in 204 patients with mixed hyperlipidaemia (fasting TG 150-499 mg/dL and LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100 mg/dL). At 24 weeks, dose-dependent reductions in TG levels of 51, 57, and 63 percentage points were observed compared with placebo (p<0.001 for all comparisons)76.

These consistent findings underscore the growing interest in therapies designed to reduce TG levels by targeting APOC3 and ANGPTL3. However, following the disappointing results of pemafibrate in the PROMINENT trial, it has become clear that novel agents are most likely required to reduce both TG levels and the total number of atherogenic particles, estimated by apolipoprotein B. Ongoing clinical trials and longer-term studies will be crucial in clarifying the role of these agents in routine clinical practice and in addressing residual cardiovascular risk.

Table 5. Examples of drugs for TG-lowering therapy currently in clinical trials.

| Target | Drug name | Mechanism of function | Trial | Phase | Target populations | N | Outcomes | Delivery method and dosage | Adverse events | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apolipoprotein C-III | Olezarsen | ASO | Bridge-TIMI 73a | 2b | Moderate hypertriglyceridaemia (TG levels 150-499 mg/dL) or severe hypertriglyceridaemia (TG ≥500 mg/dL) | 154 | 50 mg: TG levels 49.3% ↓ 80 mg: TG levels 53.1% ↓ APOC3 ↓ apolipoprotein B↓ non-HDL-C ↓ | 50 mg and 80 mg monthly, subcutaneously | Elevation in aminotransferase | 71 |

| Olezarsen | ASO | BALANCE | 3 | FCS and fasting TG >880 mg/dL | 66 | Olezarsen 80 mg: TG 43.5% ↓ | 80 mg/50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks | Diarrhoea, vomiting, chest discomfort, chills | 72 | |

| Plozasiran | ASO | SHASTA-2 | 2b | Severe hypertriglyceridaemia (fasting TG levels in the range of 500-4,000 mg/dL while receiving stable lipid-lowering treatment) | 226 | Dose-dependent reductions in TG (57%↓) compared with placebo | 10 mg/25 mg/50 mg subcutaneously on day 1 and at week 12 | Worsening glycaemic control, diarrhoea, urinary tract infection, headache | 73 | |

| Plozasiran | siRNA | PALISADE | 3 | FCS (TG ≥880 mg/dL or genetically confirmed) | 75 | 25 mg: TG 80% ↓ 50 mg: TG 78% ↓ | 25 mg/50 mg subcutaneously every 3 months for 12 months | Abdominal pain, nasopharyngitis, headache, nausea | 74 | |

| Plozasiran | siRNA | MUIR | 2b | Mixed hyperlipidaemia (TG 150-499 mg/dL and LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100 mg/dL) | 353 | Fasting TG reductions 44.2% ↓ to 62.4 % ↓ | 10 mg/25 mg/50 mg subcutaneously on day 1 and at week 12 (quarterly doses) | Worsening glycaemic control | 75 | |

| Angiopoietin-like 3 | Zodasiran | RNAi | ARCHES-2 | 2b | Mixed hyperlipidaemia (fasting TG 150-499 mg/dL and LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL or non-HDL-C ≥100 mg/dL) | 204 | Dose-dependent reductions in TG levels of 51%↓, 57%↓, and 63%↓ | Subcutaneous injections of zodasiran (50 mg/100 mg/200 mg) on day 1 and week 12 | Worsened diabetic control Urinary tract infections | 76 |

| APOC3: apolipoprotein C-III; ASO: antisense oligonucleotide; FCS: familial chylomicronaemia syndrome; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RNA: ribonucleic acid; RNAi: RNA interference; siRNA: small interfering ribonucleic acid; TG: triglyceride | ||||||||||

HDL-C therapy

Low levels of HDL-C, alongside elevated TG, represent a significant component of residual risk for atherosclerosis. Markedly low HDL-C has been associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, prompting the development of pharmacological agents aimed at raising HDL-C levels or enhancing cholesterol efflux77. In this context, ongoing research includes the evaluation of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors and mAb.

CETP inhibitors

CETP facilitates the transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins, thereby influencing plasma levels of HDL-C and LDL-C (Central illustration A). Consequently, CETP inhibition has been investigated as a strategy to raise HDL-C and lower LDL-C levels. Several agents have been developed for this purpose, as shown in Table 6, along with their most prominent trial results78. The initial trials with torcetrapib and dalcetrapib confirmed expected increases in HDL-C levels and reductions in LDL-C levels; however, these changes did not lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes7879. Notably, in the ILLUMINATE trial, which enrolled 15,067 high-risk patients, torcetrapib was associated with higher risks of MACE (HR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.09-1.44; p=0.001) and total mortality (HR 1.58, 95% CI: 1.14-2.19; p=0.006) compared with atorvastatin monotherapy, which were predominantly attributed to an off-target toxicity (blood pressure increase).

Contemporary studies have been more positive, and in the REVEAL trial, which included 30,449 adults with established ASCVD, treatment with 100 mg of anacetrapib led to a 9% reduction in cardiovascular events over four years (95% CI: 3-15%; p=0.004) with no serious adverse events reported80. Obicetrapib was studied in the BROOKLYN trial, involving 354 participants with HeFH and inadequate LDL-C control. A 10 mg dose of obicetrapib was well tolerated and, compared to placebo, resulted in significant reductions in LDL-C and favourable changes in other lipid parameters, including increased HDL-C and decreased non-HDL-C, Lp(a), and ApoB, with no significant adverse events81. The BROADWAY trial, involving 2,530 patients with HeFH or a history of ASCVD who were receiving the maximum tolerated doses of lipid-lowering therapy, demonstrated that obicetrapib reduced LDL cholesterol levels by 29.9% at 84 days versus placebo in high-risk patients (mean baseline LDL-C 98 mg/dL), with a between-group difference of –32.6 percentage points (p<0.001) and similar adverse event rates in both groups82. Running in parallel, the ongoing PREVAIL trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05202509) is evaluating whether obicetrapib reduces the risk of MACE in ASCVD patients who are not adequately controlled on lipid-lowering therapy, with results expected in the first quarter of 2026.

Table 6. Examples of drugs for HDL-C therapy currently in clinical trials.

| Target | Drug name | Mechanism of function | Trial | Phase | Target populations | N | Outcomes | Delivery method and dosage | Adverse events | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CETP inhibitor | Torcetrapib | Inhibits transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins, thus elevating HDL-C and reducing LDL-C | ILLUMINATE | 3 | Patients at high cardiovascular risk | 15,067 | HDL-C ↑: 72.1% LDL-C ↓: 24.9 % sBP {83: 5.4 mmHg Risk of CV events {83: HR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.09-1.44; p=0.001 Total mortality {83: HR 1.58, 95% CI: 1.14-2.19; p=0.006 | 60 mg daily, oral | Hypertension, peripheral oedema, angina pectoris, dyspnoea, headache | 78 |

| CETP inhibitor | Dalcetrapib | Inhibits transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins, thus elevating HDL-C and reducing LDL-C | Dal-OUTCOMES | 3 | Patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome | 15,871 | HDL-C ↑: 31-40% No significant reduction in risk of recurrent CV events: dalcetrapib: 8.3%, placebo: 8.0%; HR 1.04, 95% CI: 0.93-1.16; p=0.52 | 600 mg daily, oral | Hypertension, diarrhoea, insomnia | 79 |

| CETP inhibitor | Anacetrapib | Inhibits transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins, thus elevating HDL-C and reducing LDL-C | REVEAL | 3 | Patients with established atherosclerotic vascular disease | 30,449 | HDL ↑: 43 mg/dL LDL ↓: 17 mg/ dL CV events: 9% ↓ (95% CI: 3-15%; p=0.004) over 4 years 20% ↓ (95% CI: 10-29%; p<0.001) over 2-year follow-up | 100 mg daily, oral | No evidence of serious adverse events | 80 |

| CETP inhibitor | Obicetrapib | Inhibits transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins, thus elevating HDL-C and reducing LDL-C | BROADWAY | 3 | Participants with HeFH and inadequate LDL-C/HDL-C control | 2,530 | LDL ↓: 32.6% (95% CI: –35.8 to –29.5; p<0.001) | 10 mg once-daily, oral | No evidence of serious adverse events | 82 |

| CETP inhibitor | Obicetrapib | Inhibits transfer of cholesteryl esters from HDL-C to other lipoproteins, thus elevating HDL-C and reducing LDL-C | BROOKLYN | 3 | Participants with HeFH | 354 | LDL-C ↓: 36.3% HDL-C ↑ Lipoprotein(a) ↓ Apolipoprotein B ↓ | 10 mg once-daily, oral | Well tolerated | 81 |

| mAb | MEDI5884 | Humanised mAb developed to neutralise endothelial lipase, thereby augmenting HDL-C levels | LEGACY | 2a | Patients with stable coronary artery disease on statin therapy | 132 | 50 mg: HDL-C ↑: 5.8% (95% CI: –10.3 to 21.9; p=0.48) 200 mg: HDL-C ↑: 37.5% (95% CI: 21.8-53.2; p<0.0001) 500 mg: HDL-C ↑: 51.4% (95% CI: 35.7-67.1; p<0.0001) Functional HDL particles ↑: 14.4% (95% CI: 7.1-21.7; p=0.0001) ApoA-I levels ↑: 35.7% (95% CI: 24.2-47.2; p<0.0001) | Once-monthly subcutaneous doses (50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 350 mg, or 500 mg) | Injection site reactions (mild) | 83 |

| ApoA-I: apolipoprotein A-I; CETP: cholesteryl ester transfer protein; CI: confidence interval; CV: cardiovascular; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HDL-C: HDL cholesterol; HeFH: heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia; HR: hazard ratio; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; mAb: monoclonal antibody; sBP: systolic blood pressure | ||||||||||

Monoclonal antibody (MEDI5884)

MEDI5884 is a humanised mAb developed to neutralise EL, thereby augmenting HDL-C levels (Central illustration A). As detailed in Table 6, in the LEGACY Phase 2a trial which enrolled 132 patients with CCS on statin therapy, MEDI5884 produced a dose-dependent increase in HDL-C, together with significant increases in the number of functional HDL particles and ApoA-I levels, without causing any serious adverse events83. However, given the negative Mendelian randomisation study for EL, it is highly questionable whether the increase in HDL-C by MEDI5884 will translate into any improvement in cardiovascular outcomes.

Future directions for HDL-C-targeted therapies

Following the large number of negative trials attempting to increase HDL-C as a means of reducing residual ASCVD risk, recent research in HDL therapeutics has shifted toward enhancing HDL functionality, particularly by improving cholesterol efflux capacity and promoting reverse cholesterol transport. However, clinical trials in this area have thus far yielded mixed results84. In the Phase 2 MILANO-PILOT trial involving 122 patients with ACS, infusions of the HDL mimetic MDCO-216 (containing ApoA-I Milano) did not significantly reduce coronary plaque burden, with only a 0.21% decrease in percent atheroma volume (PAV) and a 6.4 mm3 reduction in total atheroma volume (TAV)85. Despite these modest findings, interventions designed to enhance cholesterol efflux capacity may still hold promise, particularly in patients with profoundly low baseline efflux capacity84. Other studies using ApoA-I mimetics, such as CSL111/112 and CER-001, have also yielded negative surrogate outcome data8687. As a consequence, all programmes targeting HDL increase by infusions have been discontinued.

Ultimately, while CETP inhibitors and novel mAb offer intriguing mechanisms for modulating HDL-C levels and function, their impact on cardiovascular events remains highly questionable, as the evidence supporting a beneficial impact of HDL “functionality” on cardiovascular outcome is at equipoise.

The immunological facet of cardiovascular disease

Atherosclerosis has been directly linked to inflammation, and this often underappreciated relationship may contribute to the persistent burden of ASCVD despite the widespread use of maximal lipid-lowering therapies88. This section explores atherosclerosis as an immune-mediated process and provides an overview of inflammatory biomarkers and targeted therapeutic approaches.

How inflammation fuels plaque growth

Following exposure to stressors such as smoking, elevated LDL-C levels, or hypertension, blood vessels respond by expressing adhesion molecules that facilitate the attachment of white blood cells, particularly monocytes and T-cells, to the vessel wall. Monocytes migrate beneath the endothelial layer and differentiate into macrophages, which ingest oxidised LDL, transforming them into foam cells, which are characteristic features of early plaque formation. Concurrently, T-cells infiltrate the lesion and release cytokines that sustain the inflammatory process. As plaques expand, a cascade of cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1β [IL-1β], interleukin-6 [IL-6], and tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α) propagates through the affected area, exacerbating the inflammatory state. This ongoing inflammation weakens the fibrous cap that stabilises the plaque, increasing the risk of plaque rupture89.

Anti-inflammation therapy

Colchicine

Colchicine, which has anti-inflammatory properties including an antitubulin effect that inhibits neutrophil function, has received attention for its impact on cardiovascular disease (Central illustration C)90, with several key clinical trials providing evidence of its cardiovascular benefits.

The LoDoCo trial, which was a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint (PROBE) study involving only 532 patients with CCS, demonstrated that colchicine (0.5 mg/day) reduced the risk of MACE by 67% (HR 0.33; p<0.001) over a median follow-up of 3 years, suggesting a potential role in secondary prevention91. Validation of these findings came in the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised LoDoCo2 trial in 5,522 patients with CCS, which confirmed a 31% relative risk reduction (HR 0.69; p<0.001) in MACE over a median follow-up of 28.6 months, reinforcing colchicine’s efficacy and safety92. The regional variation of the beneficial effect with an HR of 0.46 in 1,800 Australian patients versus an HR of only 0.92 in 3,300 Dutch patients has raised some questions relating to the variability of a potential benefit92. The randomised, placebo-controlled COLCOT trial investigated colchicine in 4,745 post-MI patients and reported a 23% reduction in MACE (HR 0.77; p=0.02), though concerns arose regarding non-cardiovascular mortality93. A recent meta-analysis integrating these studies concluded that colchicine reduces adverse cardiovascular events by 33%, further supporting its role in secondary prevention94.

At variance with these, the recent CLEAR trial95, which assessed colchicine in 7,062 patients with acute MI who were followed up for 3 years, and the COLICA trial96, in patients with acute decompensated heart failure, found no significant reduction in MACE (HR 0.99; p=0.93). These findings highlight the need for further research to clarify colchicine’s role across different cardiovascular populations. Major randomised controlled trials on colchicine and cardiovascular outcomes are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Major randomised controlled trials on colchicine and cardiovascular outcomes.

| Trial | Year | Groups | Target populations | N | Follow-up duration | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LoDoCo | 2013 | Colchicine vs no colchicine (a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint study) | Patients with stable CAD receiving aspirin and/or clopidogrel (93%) and statins (95%) | 282 (colchicine 0.5 mg/day) 250 (no colchicine) | 3 years (median) | The primary outcome (composite of ACS, fatal or non-fatal out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or non-cardioembolic ischaemic stroke) occurred in 5.3% in the colchicine group and 16.0% in the no-colchicine group (HR 0.33, 95% CI: 0.18 to 0.59; p<0.001, NNT 11) | 91 |

| LoDoCo2 | 2020 | Colchicine vs placebo | Patients with CCS | 2,762 (colchicine 0.5 mg/day) 2,760 (placebo) | 28.6 months (median) | The primary outcome (a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous [non-procedural] MI, ischaemic stroke, or ischaemia-driven coronary revascularisation) occurred in 6.8% in the colchicine group and in 9.6% in the placebo group (incidence: 2.5 events vs 3.6 events per 100 person-years; HR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.57 to 0.83; p<0.001) | 92 |

| COPS | 2020 | Colchicine vs placebo | Patients with ACS and evidence of coronary artery disease on coronary angiography managed with either percutaneous coronary intervention or medical therapy | 396 (colchicine 0.5 mg/day) 399 (placebo) | 12 months | The primary outcome (a composite of all-cause mortality, ACS, ischaemia-driven [unplanned] urgent revascularisation, and non-cardioembolic ischaemic stroke in a time-to-event analysis) occurred in 6.0% in the colchicine group and in 9.5% in the placebo group (log-rank p=0.09) | 114 |

| COLCOT | 2019 | Colchicine vs placebo | Patients recruited within 30 days after MI | 2,366 (colchicine 0.5 mg/day) 2,379 (placebo) | 22.6 months (median) | The primary outcome (a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalisation for angina leading to coronary revascularisation in a time-to-event analysis) occurred in 5.5% of the patients in the colchicine group, as compared with 7.1% of those in the placebo group (HR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.61 to 0.96; p=0.02) | 93 |

| CLEAR | 2024 | Colchicine vs placebo | Patients who had acute MI and were due to receive either colchicine or placebo | 3,528 (colchicine 0.5 mg/day) 3,534 (placebo) | 3 years (median) | The primary outcome (a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, recurrent MI, stroke, or unplanned ischaemia-driven coronary revascularisation, evaluated in a time-to-event analysis) occurred in 9.1% in the colchicine group and 9.3% in the placebo group (HR 0.99, 95% CI: 0.85 to 1.16; p=0.93) | 95 |

| COLICA | 2024 | Colchicine vs placebo | Patients with AHF, requiring ≥40 mg of intravenous furosemide, regardless of their left ventricular ejection fraction and inpatient or outpatient setting | 141 (colchicine 0.5 mg/day) 137 (placebo) | 8 weeks | The primary outcome, the time-averaged reduction in NT-proBNP levels at 8 weeks, did not differ between the colchicine group (–62.2%, 95% CI: –68.9% to –54.2%) and the placebo group (–62.1%, 95% CI: –68.6% to –54.3%; ratio of change 1.0) The reduction in inflammatory markers was significantly greater with colchicine: ratio of change 0.60 (p<0.001) for CRP and 0.72 (p=0.019) for IL-6 No differences in new or worsening HF episodes (14.9% with colchicine vs 16.8% with placebo; p=0.698); the need for intravenous furosemide during follow-up was lower with colchicine (p=0.043) | 96 |

| ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AHF: acute heart failure; CAD: coronary artery disease; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; CI: confidence interval; CRP: C-reactive protein; HF: heart failure; HR: hazard ratio; IL-6: interleukin-6; MI: myocardial infarction; NNT: number needed to treat; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide | |||||||

Therapies targeting the inflammatory pathways

Among the pathways involved in inflammatory signalling, IL-1β, IL-6, and the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome have emerged as key therapeutic targets. The CANTOS trial demonstrated that canakinumab, an mAb against IL-1β, reduced recurrent cardiovascular events by 15% in patients with elevated C-reactive protein following an MI, even though LDL levels did not change much97. This finding was one of the first large-scale demonstrations that turning down a single part of the inflammatory network could help. However, high costs and (albeit minor) infection risks have limited its widespread use.

Building on this concept, IL-6 inhibition has gained attention as a viable strategy. In the Phase 2 RESCUE trial, patients at high atherosclerotic risk had substantial reductions in inflammatory markers when treated with the IL-6 ligand inhibitor ziltivekimab98. These findings underscore the pivotal role of IL-6 in plaque formation and suggest that targeted blockade may help mitigate residual cardiovascular risk; however, currently, IL-6 inhibition has not yet reached clinical use.

Beyond cytokines, the NLRP3 inflammasome has gained prominence as a central regulator of IL-1β and IL-18 maturation. Peptidomimetic inhibitors of caspase-1, such as VX-765 and VX-740, aim to reduce proinflammatory cytokine release at an upstream level (Central illustration C)99. Although large-scale cardiovascular outcome trials are lacking, early-phase studies and animal models have demonstrated that these agents attenuate vascular inflammation and plaque development. Additionally, natural compounds like arglabin have shown similar inhibitory effects on NLRP3 activation100, but human clinical data remain limited.

Targeting key inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, and the NLRP3 inflammasome represents a promising frontier in the management of CAD. While trials like CANTOS and RESCUE provide compelling evidence for the efficacy of specific anti-inflammatory therapies, further research is essential to establish their long-term safety and clinical applicability.

Inflammation and imaging: emerging strategies to address residual risk

Persistent inflammation continues to play a central role in residual cardiovascular risk. In the ASCOT-LLA 20-year follow-up, baseline hs-CRP was found to be a strong independent predictor of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, despite optimal blood pressure and lipid control101.

These findings are supported by contemporary data in suspected ACS, where even mildly elevated hs-CRP (<15 mg/L) was independently associated with increased short- and medium-term mortality, regardless of troponin levels102.

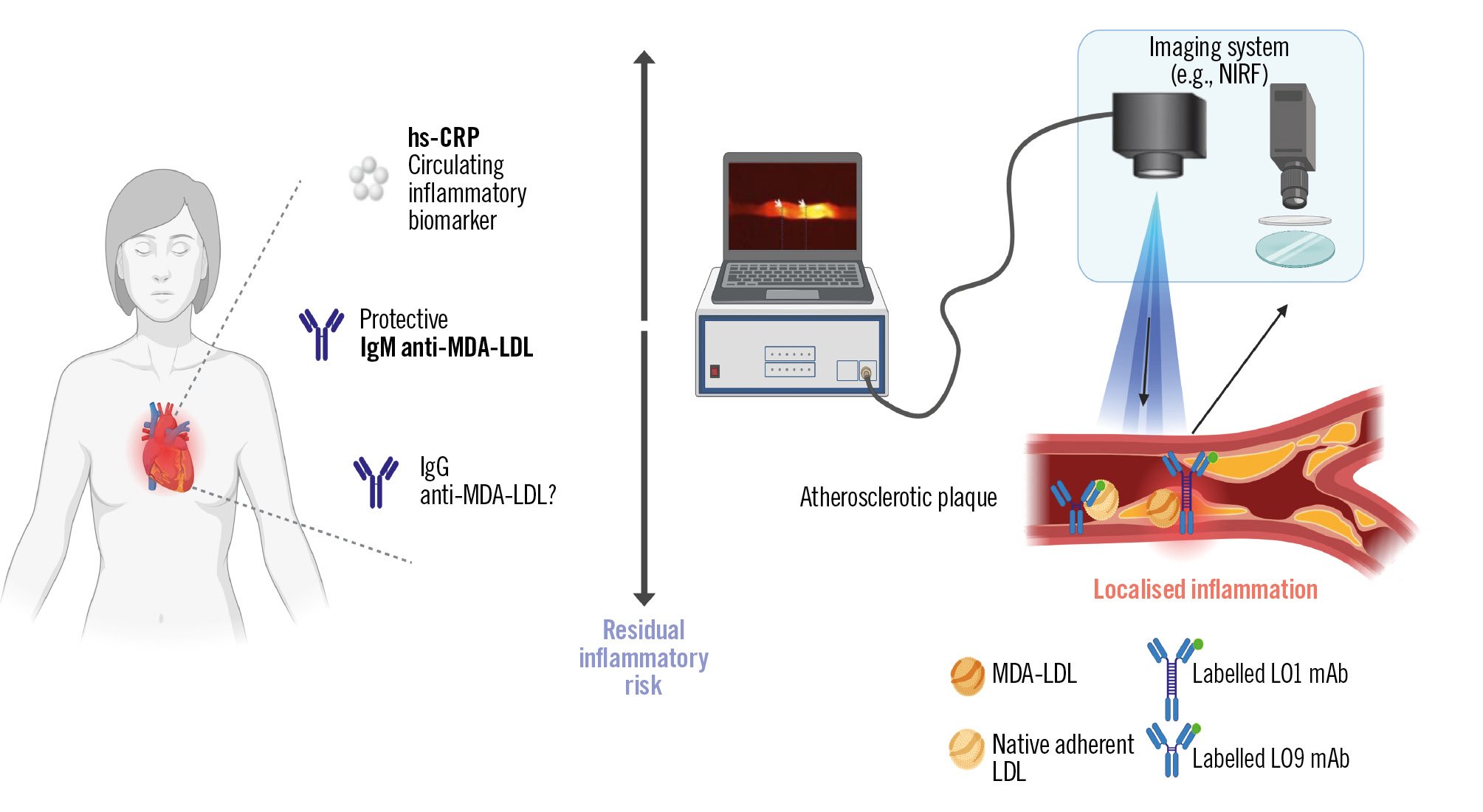

In parallel, progress has been made in the development of imaging agents that may allow direct visualisation of high-risk plaque biology (Figure 1). LO1, an mAb against malondialdehyde-modified LDL, and LO9, an immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody that recognises a cryptic epitope on matrix-adherent native LDL, have both shown selective localisation to plaque in preclinical models. LO1 enables near-infrared fluorescence imaging of oxidised lipid within a necrotic core, while LO9 targets subendothelial native LDL deposits in murine and human atherosclerotic tissue103104 (Figure 1). Both agents remain in the preclinical phase and are being refined for potential first-in-human studies.

These tools are mechanistically distinct from circulating immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to oxidised LDL, which serve as systemic biomarkers. Lower titres of IgM anti-MDA-LDL have been associated with incident coronary events and with greater necrotic core burden and lipid-rich plaque features in imaging substudies from NORDIL and IBIS-3105.

Together, these advances in systemic biomarker profiling and lesion-targeted imaging provide complementary perspectives on atherosclerotic disease activity and hold promise for more precise approaches to secondary prevention.

Figure 1. The vision for inflammation-based theranostics for residual inflammatory risk. Systemic biomarkers such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and circulating antibodies to malondialdehyde-modified low-density lipoprotein (MDA-LDL) provide measures of inflammatory and immune status. Lesion-targeted imaging with monoclonal antibodies LO1 (against MDA-LDL) and LO9 (against matrix-adherent native LDL) would in future enable the detection of localised plaque’s biological characteristics (e.g., with near-infrared fluorescence [NIRF] imaging). Created with BioRender.com. IgG: immunoglobulin G; IgM: immunoglobulin M; mAb: monoclonal antibody

Cost-effectiveness, reimbursement and therapeutic prioritisation/optimisation in secondary prevention

The cost-effectiveness of a new therapy, whether pharmacological or an implantable device, is a rapidly evolving area in medicine that strongly relies on the uniqueness of the product, the exclusivity of the manufacturer, and the competitive market. Reimbursement is primarily dependent on approval by regulatory bodies and the socioeconomic structures of healthcare systems in different countries and continents.

A 2024 study assessed the impact of China’s National Drug Price Negotiation policy on the accessibility and affordability of PCSK9 inhibitors (evolocumab and alirocumab): a reimbursement coverage of about 70% led to a massive drop in out-of-pocket costs – from catastrophic levels (~89%) down to manageable (~6%). This offers a compelling example of how national negotiation policies can shift affordability in lipid-lowering drugs106.

As discussed earlier in this review, although PCSK9 inhibitors have demonstrated strong efficacy in clinical trials, a small subset of patients may show a suboptimal LDL-C response in real-world practice. Most apparent cases are explained by modifiable factors such as missed doses, improper injection technique, or suboptimal concomitant therapy107. Identifying and addressing these factors is essential to enhance the cost-effectiveness of treatment and to maximise the sustained CV risk reduction achieved with these agents.

In terms of strategies, it is advisable to use drugs that have become generic and potentially combine them in a single pill with multiple pharma components with complementary pharmacological activities, such as rosuvastatin+ezetimibe. This approach follows the example given by Salim Yusuf and his colleagues, who have demonstrated the benefit of a polypill combining an antiplatelet agent, a statin, a beta blocker, and angiotensin inhibitors108.

Finally, treatment of the highest-risk patients must be prioritised, and they must benefit from the most aggressive and high-intensity pharmacological treatment; by default, patients either surgically or percutaneously revascularised belong to “high” or “extremely high” risk categories23.

Conclusions

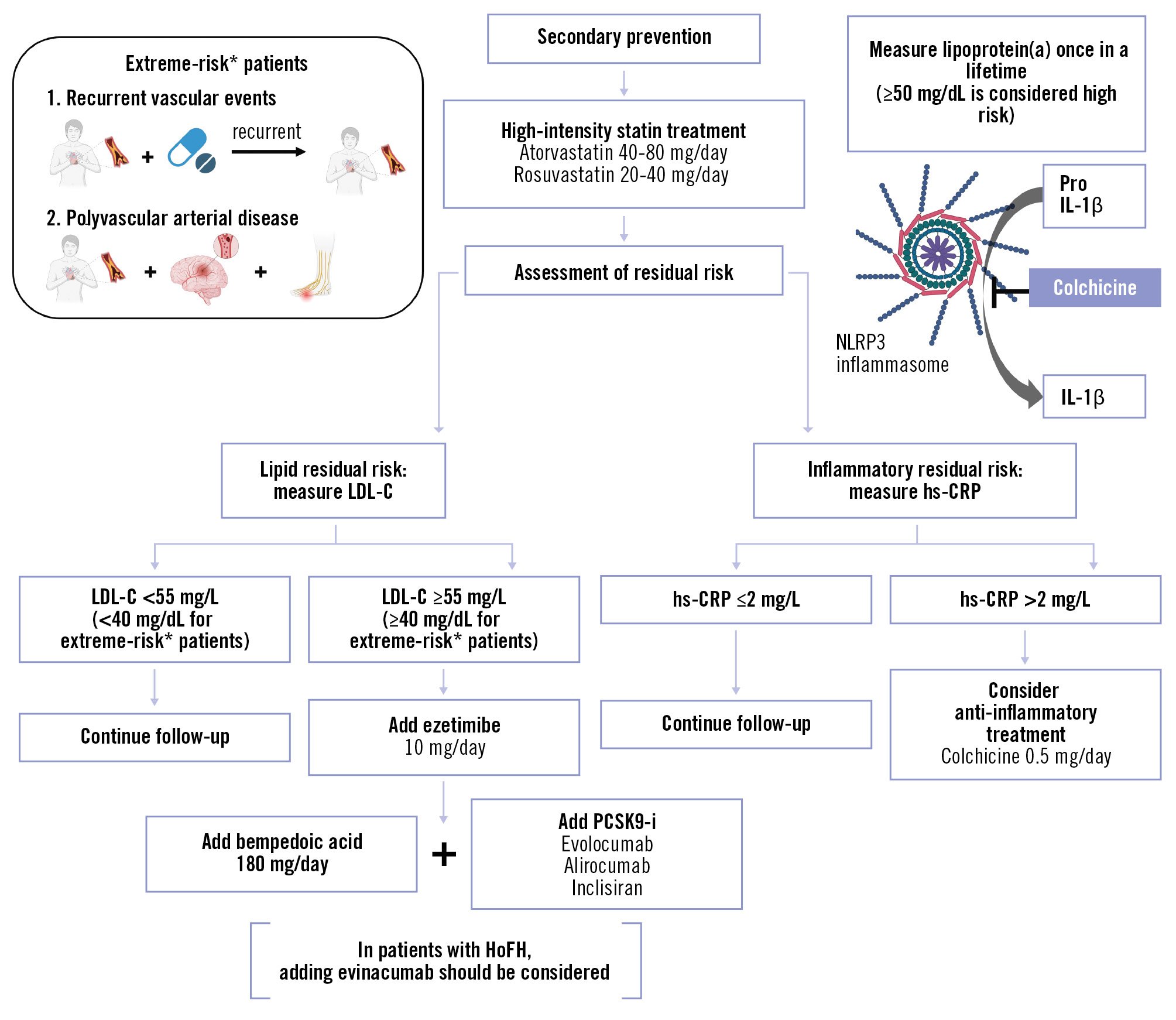

In this narrative review, we have provided an overview of lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory therapies for patients with CAD, encompassing both well-established medications, such as statins, and the latest investigational drugs in development. Our previous research has demonstrated that in patients with severe CAD, the absence of statin therapy is associated with significantly worse 10-year outcomes109. Yet the contemporary INTERASPIRE study of 4,548 patients from 14 countries across all six World Health Organization (WHO) regions continues to show that the vast majority of coronary patients do not achieve the LDL-C target of <1.4 mmol/L with wide variations in care between countries110. For all physicians managing CAD, statins are indispensable as a foundation treatment prescribed at optimal doses to achieve guideline-based targets together with other evidence-based drugs for the optimal lipid profile in all our patients. The concept of “pharmacological revascularisation” is exemplified by the EVAPORATE trial70111, which demonstrated significant coronary plaque regression and improved coronary physiology with icosapent ethyl. Similarly, Han et al112, showed that 18 months of evolocumab treatment led to a favourable shift toward lower-risk quantitative plaque phenotypes and reduced microcalcification activity. Together these studies highlight the emerging potential of medical therapy to manage, and possibly reverse, progression of CAD. As a practical proposal to address the question of how we, as interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, should approach dyslipidaemia and inflammation in daily practice, a suggested strategy is displayed in a flowchart, which is included to provide guidance for real-world clinical decision-making (Figure 2)3113. We hope that this review aids in selecting additional therapeutic options beyond statins, thereby enhancing the management of lipid disorders and inflammation in CAD.

Figure 2. Suggested strategy for managing residual lipidic and inflammatory risk. *Extreme-risk patients are defined as those with ASCVD who experience recurrent vascular events despite maximally tolerated statin-based therapy, and those with polyvascular arterial disease (e.g., coronary and peripheral). Created with BioRender.com. ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; HoFH: homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1 beta; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NLRP3: nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; PCSK9-i: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor; Pro IL-1β: precursor form of interleukin-1 beta

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tania Sharma and Lisa Ribau for their assistance in the preparation of Figure 1.

Conflict of interest statement

P.W. Serruys reports consulting fees from SMT, Meril Life Sciences, and Novartis. S. Garg reports consulting fees from Biosensors; and payment or honoraria for lectures from Novartis. F. Sharif reports a grant from Science Foundation Ireland (grant number 17/RI/5353). R. Mehran reports grants from Abbott, Alleviant Medical, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Concept Medical, CPC Clinical Research, Cordis, Elixir Medical, Faraday Pharmaceuticals, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, MedAlliance, Mediasphere Medical, Medtronic, Novartis, Protembis GmbH, RM Global Bioaccess Fund Management, and Sanofi US Services, Inc.; consulting fees from Elixir Medical, IQVIA, Medtronic, Medscape/WebMD Global, and Novo Nordisk; honoraria for lectures from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Board of Trustees; leadership or fiduciary roles in the American Medical Association (AMA; JAMA Associate Editor), the American College of Cardiology, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions; stock or stock options in Elixir Medical, Stel, and ControlRad; and other interests with the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Faculty, and Women as One (no fees). M.J. Budoff reports grants or contracts from Amgen and Novartis; payment or honoraria for lectures from Amgen; and participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board of the V-PLAQUE trial (NCT05360446). J.J. Kastelein reports being an employee of NewAmsterdam Pharma and Marea Therapeutics and has stocks or options in these. E.S.G. Stroes reports consulting fees from Amgen, Ultragenyx, Novartis, Ionis, Novo Nordisk, Merck & Co, and AstraZeneca. W. Koenig reports grants or contracts from Singulex, Dr. Beckmann Pharma, Abbott, and Roche Diagnostics; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Amgen, Pfizer, The Medicines Company, DalCor Pharmaceuticals, Kowa, Corvidia Therapeutics, OMEICOS, Daiichi Sankyo, Novo Nordisk, NewAmsterdam Pharma, TenSixteen Bio, Esperion, and Genentech; and payment or honoraria for lectures from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Amgen, Berlin-Chemie, Sanofi, and AstraZeneca. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.