Abstract

Aims: The causative relationship between major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and the increase in mortality and morbidity has frequently been suggested in recent pharmaco-invasive trials and registries. However, the magnitude of this increased risk is the subject of debate. In order to determine the prognostic significance of major bleeding in ACS, we have conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods and results: Databases were searched for articles published up to March 2007. Any study, either retrospective or prospective, assessing the impact of major bleeding in patients with ACS was included if all-cause mortality was reported as an outcome measure.

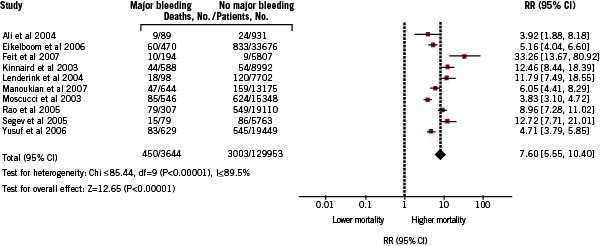

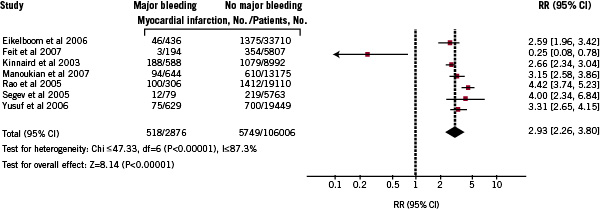

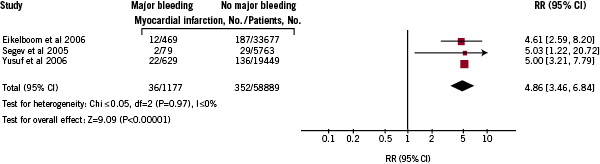

Data from 10 studies involving a total of 133,597 patients with ACS at baseline, of whom 3,644 had major bleeding (2.7%) were included in a meta-analysis using a random-effects model. An overall pooled relative risk (RR) mortality increase of 7.6 (95% CI; 5.5-10.4) was found in patients with major bleeding. Although most of the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the primary studies overlapped, some heterogeneity was observed (Chi2 for heterogeneity, P <0.0001), hence the need for the random-effects meta-analysis. However, the overall effect was highly significant (Z=12.65; P <0.00001). Major bleeding in ACS was also associated with a statistically significant increase in the secondary endpoints assessed including acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and stroke.

Conclusions: This meta-analysis indicates that major bleeding in patients with ACS is a strong predictor of in-hospital or 30-day death and AMI. The pooled estimates presented should alert clinicians and interventionalists to the importance of prevention of major bleeding in patients hospitalised with ACS.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) are the leading causes of death and cardiovascular morbidities in developed countries. As the use of improved antithrombotic strategies continues to reduce the incidence of ischaemic events rates in patients with ACS treated either conservatively or with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), bleeding is becoming the most common complication of antithrombotic treatment1-2. The causative relationship between major bleeding in ACS and the increase in mortality and morbidity has recently been suggested in several publications3-12. Indeed, pharmacological and technological advances have decreased ischaemic complications to the point that bleeding events have possibly become a greater mortality risk for ACS patients than ischaemic events. In keeping with this, major bleeding has now become a primary target for further improvement in outcomes8,12. As an early invasive strategy associated with aggressive antithrombotic regimens seems to be accepted as the best option for the treatment of ACS12-13, it is increasingly important to quantify the increased risk associated with potential bleeding to better determine where to concentrate efforts to reduce mortality in daily practice and future trials. Therefore we have conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to elucidate the prognostic significance of major bleeding in ACS.

Methods

Study inclusion criteria

Any study, either retrospective or prospective, assessing the impact of major bleeding in patients with ACS was included if: (i) Major bleeding was assessed by means of specific or established definitions (TIMI, GUSTO); (ii) In-hospital and/or 30-day follow-up was ensured; (iii) The study reported all-cause mortality as an outcome measure.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was total mortality rate comparing patients with ACS with or without major bleeding. Secondary outcomes included non-fatal myocardial infarction and stroke.

Data sources

Relevant studies were identified by systematic searches of the scientific literature for all reported observational studies of ACS and major bleeding. The databases searched to find articles were MEDLINE, Cochrane library and BioMedCentral. Experts in the field were also contacted. The search was not restricted to English language articles. The search strategy used both key words and the MeSH term searches, and took the form of (acute coronary syndromes or synonyms) and (bleeding or haemorrhage or synonyms) and (mortality or prognosis or synonyms). To identify additional studies reference lists of retrieved articles were inspected.

Study selection and data extraction

Based on careful study of the abstracts of identified articles, studies were excluded if they were not relevant. Two reviewers (MH and EF) independently assessed studies to determine eligibility and independently carried out data extraction using a standardised form. Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus.

Criteria to assess quality

Unlike randomised controlled trials, no generally accepted list of appropriate criteria for observational studies is available. Rather than producing a simple arbitrary quality score, specific quality aspects were used to assess the studies such as control of confounding factors, minimisation of selection bias, definition used for the diagnosis of major bleeding, the antithrombotic regimen used, the year of publication, the study type and the sample size.

Data synthesis

All analyses were carried out using RevMan 4.2 software. Studies were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was analysed with Chi2 and I2 statistics. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level on the basis of two-way Z-tests. Kappa statistic was calculated to determine inter-observer agreement. Publication bias was assessed graphically using Funnel plots.

Results

Description of studies

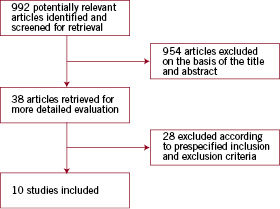

Of the 992 articles screened, 38 were considered in-depth for inclusion, but 28 were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study selection process.

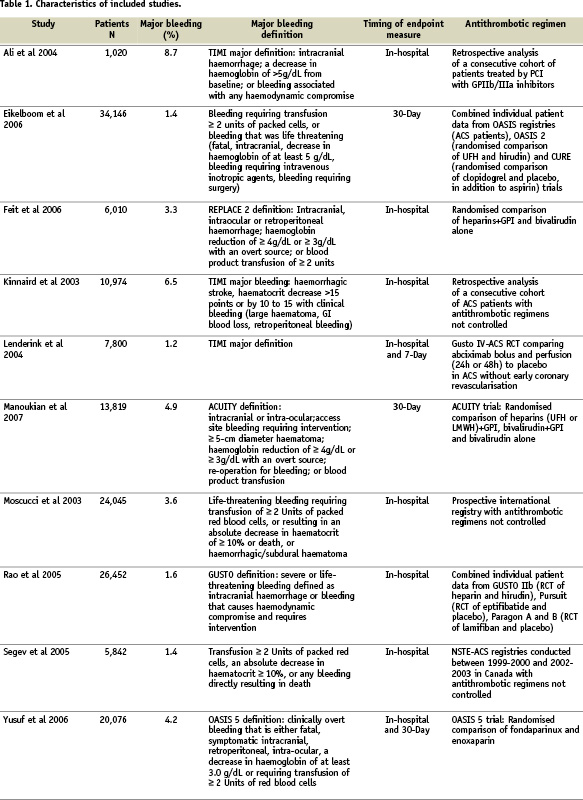

Ten studies met all inclusion criteria and had sufficient data available. Agreement between the two reviewers for study eligibility was very high (Kappa=0.9). These studies had a total sample size of 133,597 patients with ACS at baseline in 98% of cases, of whom 3,644 had major bleeding (2.7%) (Table 1).

Early mortality (in-hospital or 30-day), the primary end-point of the present meta-analysis, was clearly stated in all studies.

Quality assessment of included studies

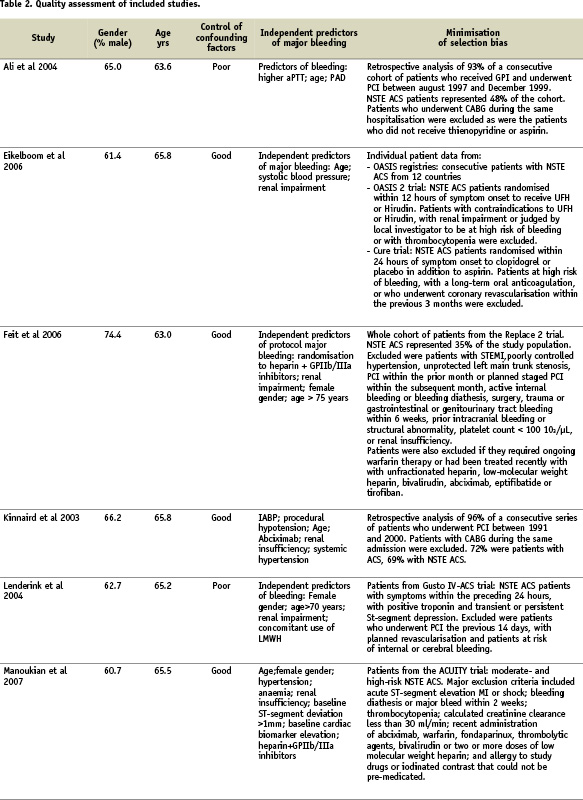

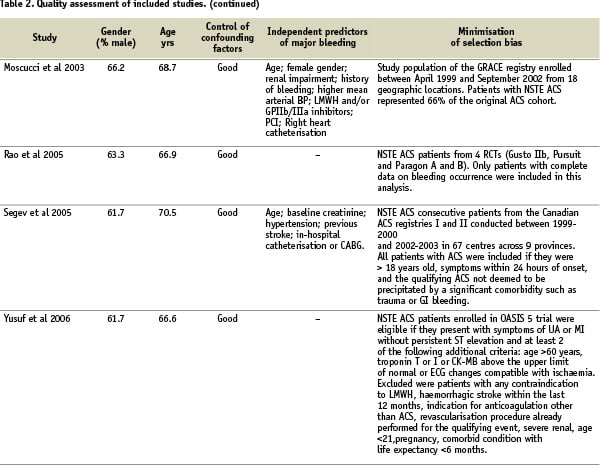

Quality assessment criteria included the sample size, clear definitions of major bleeding and of the cardiac events, the extent of the follow-up, the adequacy of control for confounding factors, and minimisation of selection bias (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis

Follow-up for in-hospital or 30-day mortality was exhaustive. A sensitivity analysis was carried out including only those studies that were prospective including exclusively NSTE ACS patients with major bleeding prespecified as an endpoint measure and with antithrombotic regimens partly controlled by study protocol. The increase in mortality rate estimated by this analysis including five studies (RR, 6.7; 95% CI, 4.8-9.3) and the analysis including all 10 studies (RR, 7.6; 95% CI, 5.5-10.4) did not differ significantly.

Control of confounding factors

Assessing control of confounding factors was carried out independently by two reviewers using prespecified criteria. These criteria included age, gender, antithrombotic treatments, CHD risk factors, history of previous MI and comorbidities. Control of confounding factors was classified as poor if little or no attempt was made to measure or control for known basic confounders such as age and gender (Table 2). Adequate control considered at least these basic confounders, and good control considered the majority of the clinical variables previously mentioned. Reviewer agreement was very good (Kappa=0.88). Control of confounding factors was good in eight studies with adjusted estimates of the mortality increase related to major bleeding provided in six studies.

Total mortality

A random-effects meta-analysis was carried out, and an overall pooled RR mortality increase of 7.6 (95% CI; 5.5-10.4) was found (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pooled relative risks of mortality increase in patients with ACS and major bleeding: random-effects meta-analysis of 10 studies.

Although several of 95% CIs for the primary studies overlapped, some heterogeneity was observed in prospective studies (Chi2 for heterogeneity, P <0.0001), hence the need for the random-effects meta-analysis. However, the overall effect was highly significant (Z=12.65; P<0.00001) and the results did not differ when the analysis was limited to prospective or retrospective studies. Funnel plots were created to compare the SE of the Log OR with the Log OR, revealing possible publication bias. Larger, more precise studies with smaller SEs tended to find smaller impact in risk of mortality increase in patients with major bleeding than did smaller studies with more deaths, and therefore larger SEs (not shown).

Morbidity outcomes

Acute myocardial infarction

Seven studies presented information on myocardial infarction occurrence during the hospital stay according to incidence of major bleeding in patients with ACS (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pooled relative risks of myocardial infarction increase in patients with ACS and major bleeding: random-effects meta-analysis of 7 studies.

The pooled RR for MI was 2.9 (95% CI; 2.3-3.8).

Stroke

Three studies presented information on stroke occurrence (Figure 4) and the pooled RR was 4.9 (95% CI; 3.5-6.8).

Figure 4. Pooled relative risks of stroke increase in patients with ACS major bleeding: random-effects meta-analysis of 3 studies.

All aforementioned pooled RR estimates for morbidity outcomes were highly significant (P<0.0001).

Discussion

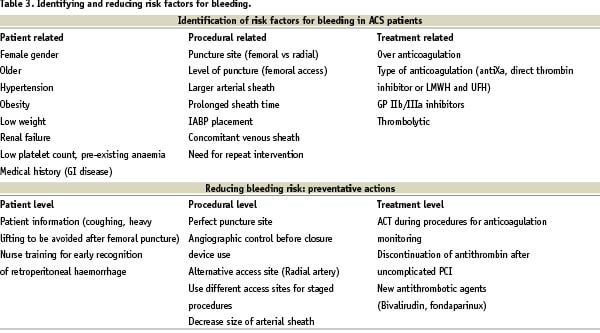

This meta-analysis indicates that major bleeding in patients with ACS is associated with a significantly worse prognosis. Previous studies examining the prognostic impact of major bleeding in patients with ACS have involved moderate to high numbers of patients, but with low rate of outcome events leading to wide confidence intervals in the point estimates provided. Our meta-analysis clearly demonstrated that major bleeding is associated with a significant increase in mortality (7.6-fold) and severe complications such as myocardial infarction (3-fold), and stroke (5-fold). These pooled estimates with narrow limits are important for cardiologists and other clinicians working in intensive care units, emergency departments or catheterisation laboratories. Indeed early recognition of bleeding risk during ACS, is of critical importance in attempting to limit, by preventative actions, its deleterious effect on patient outcomes. Pre-procedural risk assessment of bleeding complications is possible and should be taken into account in defining risk versus benefit of an invasive strategy (Table 3).

It is not clear if major bleeding by itself explains this mortality increase or if it does so indirectly by impacting renal function, predisposing to myocardial ischaemia, affecting platelet activation or increasing the need for subsequent blood transfusion and therefore leading to inflammatory responses as recently suggested14,15. However, transfusion is the strongest predictor of length of in-hospital stay after PCI, and is demonstrated to be associated with increased mortality in patients with underlying coronary artery disease15. Furthermore, bleeding and anaemia lead to discontinuation of aspirin and/or thienopyridines causing ischaemic complications that may also explain the increased morbidity and mortality. In the recently published paper of Manoukian et al, major bleeding in moderate- and high-risk ACS patients was also associated with the risk of stent thrombosis8.

As indicated by quality assessment of the studies included in the present meta-analysis, antithrombotic regimens vary from one study to another and can interact with the rate of major bleeding. Sensitivity analyses show that the analysis restricted to prospective studies with controlled antithrombotic regimen lead to the same results of deleterious impact of major bleeding on patient outcomes. Early invasive strategy can improve clinical outcome, but major bleeding at the vascular access site is currently the most common non-cardiac complication of therapy for patients with coronary artery disease who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1-2. Our results are in keeping with previous studies which have indicated that patients who experience a major bleed in the course of an acute coronary syndromes exhibit a much higher risk of death during the immediate weeks following the event. The combination of antithrombotic therapies used in the last two decades has substantially decreased the risk of a heart attack after PCI procedures, but has also been associated with a significant increase in bleeding risk. On the other hand, it must also be acknowledged that the predictive factors for death during the initial phase of ACS management largely overlap with the risks factors for bleeding. Indeed the patients at highest risk of ischaemic complications and therefore exposed to more aggressive treatment strategies, including invasive strategies and antithrombotic regimens, are also at the highest risk for bleeding. Therefore, therapies or strategies that maintain the benefits of currently available antithrombotic therapies, but lead to less bleeding, are of great clinical importance. Risk factors that have been demonstrated in large trials to be of importance are listed in Table 3 according to patient factors, procedural factors and treatment factors, and potential preventative measures are suggested. From this perspective fondaparinux has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of non-ST elevation ACS, while simultaneously reducing bleeding. Despite some controversy related to the wide non-inferiority margin chosen in the ACUITY trial, a bivalirudin-alone strategy also appears to be an acceptable approach to the management of non ST elevation ACS in the context of early invasive management and bleeding reduction12,13-16. The transradial approach is also a simple method which is able to drastically reduce entry site complications and therefore a substantial number of major bleeding events frequently occurring at access sites17.

Limitations of review

This review has a number of limitations. First, we are considering observational data. Patients with ACS and major bleeding may well differ from those without major bleeding in a number of ways including their age, gender, risk factors and acute treatment that they received because of the ACS. However the direction of these potential confounding factors is not obvious. Some studies found that the subsequent mortality risk with major bleeding was restricted to elderly patients or female patients, while others suggested that major bleeding is an independent and strong predictor of mortality. The present meta-analysis was carried out using crude estimates. Six studies also presented adjusted outcome measures for total mortality using markedly different adjustment methods to consider different covariates and were measured in varying ways. Perhaps surprisingly however, results of these six studies found only small differences between adjusted and non-adjusted estimates. In fact, the RR increase appeared sometimes greater after adjustment in some studies, suggesting that our estimates may be conservative, and may slightly underestimate the true risk increase associated with major bleeding in patients with ACS.

Definitions used in recent trials differ from TIMI or GUSTO definitions and are more sensitive. However the ability of these more specifically designed major bleeding definitions (for ACS and invasive strategies) to predict mortality constitutes a validation of these definitions. Future trials should be consistent in defining bleeding complications to objectively assess the rates of haemorrhagic events using different antithrombotic regimens.

As with any systematic review, there is a possibility of publication bias, as suggested, by the funnel plot (not shown). However, exclusion of the smaller studies in a sensitivity analysis made essentially no difference to the pooled RR.

Conclusions

Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence of the deleterious impact of major bleeding in ACS and because of the evidence of superiority of early invasive strategy in ACS, preprocedural risk assessment of bleeding should be routinely performed in all patients with a diagnosis of ACS18. Identification of bleeding risk in ACS, which predicts mortality and serious adverse events, should be taken into account when assessing the risk benefit ratio of the procedure and promoting preventative actions (as proposed in Table 3).