Abstract

Intracoronary (IC) imaging-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) improves clinical outcomes in patients with high clinical and anatomical risk when compared to interventions guided by angiography alone. Recent Class I recommendations for the use of IC imaging guidance when performing PCI in left main stem or complex lesions may result in a significant uptake as the technology is embraced as standard of care. Routine application of IC imaging will provide interventional cardiologists with a wealth of high-fidelity intracoronary data on plaque composition and distribution. When paired with emerging data regarding the importance of plaque anatomical characteristics, developments in artificial intelligence and computational fluid dynamics, lesion stratification with IC imaging may herald the next paradigm shift in this field. In this review, we will explore this important emerging application of IC imaging to inform morphology-guided PCI, identify high-risk lesions for targeted therapies, and consider the prospects of harnessing automated image interpretation with artificial intelligence technologies to achieve an integrated physiological and morphological assessment. Lesion stratification with IC imaging has the potential to shape the future of interventional cardiology practice to guide therapies within and beyond the confines of the cardiac catheterisation laboratory.

Our understanding of atherosclerosis and existing therapeutic approaches have evolved in parallel with technologies to assess and evaluate coronary plaque. Intracoronary (IC) imaging facilitates in vivo assessment of the anatomical features of coronary lesions with near-histological precision and has revolutionised our understanding of the mechanisms underpinning both chronic (CCS) and acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Application of IC imaging in clinical practice has primarily concentrated on guidance and optimisation of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), with observed reductions in target vessel failure (TVF), target vessel myocardial infarction (TVMI), and all-cause mortality when compared to angiography-guided interventions1. Recently, the use of IC imaging to guide PCI for left main stem (LMS) or anatomically complex lesions received a Class I, Level of Evidence A recommendation, and this is likely to lead to a substantial increase in the use of IC imaging23.

Routine assessment of lesion morphological characteristics with IC imaging may offer important additional information, with the potential to transform our understanding of coronary artery disease (CAD) and its therapies across the clinical spectrum. For example, identification of lesions with high-risk characteristics may inform a burgeoning field of targeted therapies to pacify “vulnerable” lesions and prevent future events4. Evaluation of culprit lesions in ACS may help to evolve interventional and pharmacological approaches for managing the disease5. Finally, through developments in automated IC image interpretation, powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and advances in computational fluid dynamics modelling of coronary flow, IC imaging technologies may now render the dichotomous functional versus morphological approach to lesion stratification redundant.

In this review, we will appraise the evidence and guidelines supporting the current application of IC imaging in clinical care. We will then describe a contemporary approach to the use of IC imaging for assessment and stratification of lesion morphology during PCI planning, emerging concepts of IC imaging-guided therapy in ACS, the characterisation and treatment of the high-risk plaque, and the promise of a complete morphofunctional lesion assessment from IC imaging alone. We are entering an era where IC imaging use for the evaluation and treatment of CAD is likely to become widespread. By embracing its potential, whilst undertaking robust clinical validation, we can shape interventional cardiology practice in the coming decade.

Intracoronary imaging & current international guidelines

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are the IC imaging modalities currently used in routine clinical practice. Globally, IC imaging use remains low with substantial geographical variation and barriers to adoption, including concerns about reimbursement, time constraints, and confidence with image interpretation. In Japan, documented rates of IC imaging-guided PCI approach 85%, while in the United States, IC imaging is used to guide just 15-20% of PCI6.

Since 2015, almost 20,000 patients, across the spectrum of stable and acute syndromes, have been included in international randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing IC imaging-guided PCI against angiographic-guided intervention. Taken in concert, these studies clearly demonstrate the superiority of IC imaging over angiography-guided PCI (Table 1)7891011121314. International guidelines now state that IC imaging should be used to guide intervention in LMS and anatomically complex lesions, regardless of clinical syndrome (Class I, Level of Evidence A)23.

IC imaging informs interventional device sizing, identification of landing zones, and early correction of prognostically relevant complications, such as stent strut malapposition, stent underexpansion, edge dissection, and inadequate lesion coverage. When compared directly in clinical trials, or indirectly in network meta-analyses, the benefits of using OCT and IVUS to guide and optimise PCI appear equivalent15. The choice of IC modality may be guided by the clinical scenario and the relative strengths of each device.

IVUS is preferred in assessment of the LMS due to its ability to assess the ostial segment and its superior depth of penetration. In patients with angiographically intermediate LMS stenoses, assessment with IVUS should be considered to guide revascularisation decision-making (Class IIa, Level of Evidence B)2. In an ACS, where there remains ambiguity in identifying the culprit lesion following angiographic assessment, guidelines state that IC imaging (preferably with OCT) should be used to facilitate diagnosis and guide therapeutic decision-making (Class IIb, Level of Evidence C)16. In patients with suspected stent failure, however, either OCT or IVUS may be used to detect the causative mechanism and mode of failure (Class IIa, Level of Evidence C)17.

Table 1. Randomised controlled trials comparing clinical outcomes following PCI guided by intracoronary imaging versus angiography guidance.

| Trial | Enrolled, n (Randomisation ratio) | IC imaging modality | Follow-up, months | Lesion complexity | Endpoint | Results | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTO-IVUS (2015)7 | 402 (1:1) | IVUS vs angio | 12 | Chronic total occlusion | Composite of cardiac death, TLMI or ischaemia-driven TLR | 5 (2.6%) vs 14 (7.1%) (HR 0.35, 95% CI: 0.13-0.97; p=0.035) | Primary outcome was cardiac death; 0 in IVUS group vs 2 in angio-only group Korea only |

| IVUS-XPL (2015)8 | 1,4 (1:1) | IVUS vs angio | 12 | Long lesions ≥28 mm | Composite of cardiac death, TLMI or ischaemia-driven TLR | 19 (2.9%) vs 39 (5.8%) (HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.28-0.83; p=0.007) | 94.5% follow-up at 12 months Korea only |

| ULTIMATE (2018)9 | 1,448 (1:1) | IVUS vs angio | 12 | All-comers 8.9% CTO 12.6% unprotected left main 34.2% any bifurcation Avg. stent length ~48 mm 24.8% moderate to severe Ca2+ | Composite of cardiac death, TVMI or clinically indicated TVR | 21 (2.9%) vs 39 (5.4%) (HR 0.53, 95% CI: 0.31-0.90; p=0.02) | Minimum operator volume: 200 PCI/yr China only |

| RENOVATE-COMPLEX-PCI (2023)10 | 1,639 (2:1) | OCT or IVUS vs angio | 24 | Complex lesions 19.5% CTO 11.7% unprotected left main 21.9% true bifurcation 54.8% long lesion (≥38 mm) 37.9 % multivessel PCI 14.1% severe Ca2+ | Composite of cardiac death, TVMI or clinically indicated TVR | 76 (7.7%) vs 60 (12.3%) (HR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.45-0.81; p=0.008) | Korea only |

| OCTOBER (2023)11 | 1,201 (1:1) | OCT vs angio | 24 | True bifurcations with SB diameter ≥2.5 mm 18.9% LMS 70.5% LAD/D1 | Composite of cardiac death, TLMI or ischaemia-driven TLR | 59 (10.1%) vs 83 (14.1%) (HR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.50-0.98; p=0.035) | Europe only 15.3% IVUS use in the angiography arm |

| ILUMIEN IV (2023)12 | 2,487 (1:1) | OCT vs angio | 24 | Complex lesions and/or T2DM 7.0% CTO 3.4% two-stent bifurcation 67.6% long lesion (≥28 mm) 11.5% severe Ca2+ 5.5% STEMI culprit 24.1% non-STEMI culprit | Composite of cardiac death, TVMI or ischaemia-driven TVR | 88 (7.4%) vs 99 (8.2%) (HR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.67-1.19; p=0.45) | 18 countries in Europe, North America, Asia & Oceania Co-primary endpoint of final MSA was 5.72±2.04 mm² vs 5.36±1.87 mm² (p<0.0001) |

| IVUS-ACS (2024)13 | 3,505 (1:1) | IVUS vs angio | 12 | Acute coronary syndromes 27.6% STEMI 4.3% unprotected left main 15.2% true bifurcation 72.5% long lesion (≥30 mm) 7.6% moderate to severe Ca2+ | Composite of cardiac death, TVMI or clinically indicated TVR | 70 (4.0%) vs 128 (7.3%) (HR 0.55, 95% CI: 0.41-0.74; p=0.0001) | China (52 centres), Pakistan (2), UK (1), Italy (1) Minimum of 1,000 PCI per site* & 200 PCI per operator Patients underwent a second randomisation to DAPT vs ticagrelor monotherapy |

| OCCUPI (2024)14 | 1,604 (1:1) | OCT vs angio | 12 | Complex lesions 7.2% CTO 20.4% acute myocardial infarction 14.3% unprotected left main 23.8% true bifurcation 71.8% long lesion (≥28 mm) 9.3% severe Ca2+ 8.1% intracoronary thrombus 10.7% in-stent restenosis | Composite of cardiac death, MI, stent thrombosis, or ischaemia-driven TLR | 37 (4.6%) vs 59 (7.4%) (HR 0.62, 95% CI: 0.41-0.93; p=0.023) | Korea only Initial 2x2 factorial analysis with assessment of 3-month DAPT vs 12-month DAPT abandoned due to concern about the lack of equipoise in this cohort |

| *Except for the UK site. Ca2+: calcification; CI: confidence interval; CTO: chronic total occlusion; D1: first diagonal branch; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; HR: hazard ratio; IC: intracoronary; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; LAD: left anterior descending artery; LMS: left main stem; MI: myocardial infarction; MSA: minimum stent area; OCT: optical coherence tomography; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SB: side branch; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; TLMI: target lesion myocardial infarction; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVMI: target vessel myocardial infarction; TVR: target vessel revascularisation | |||||||

Lesion characterisation & evolving concepts in PCI planning

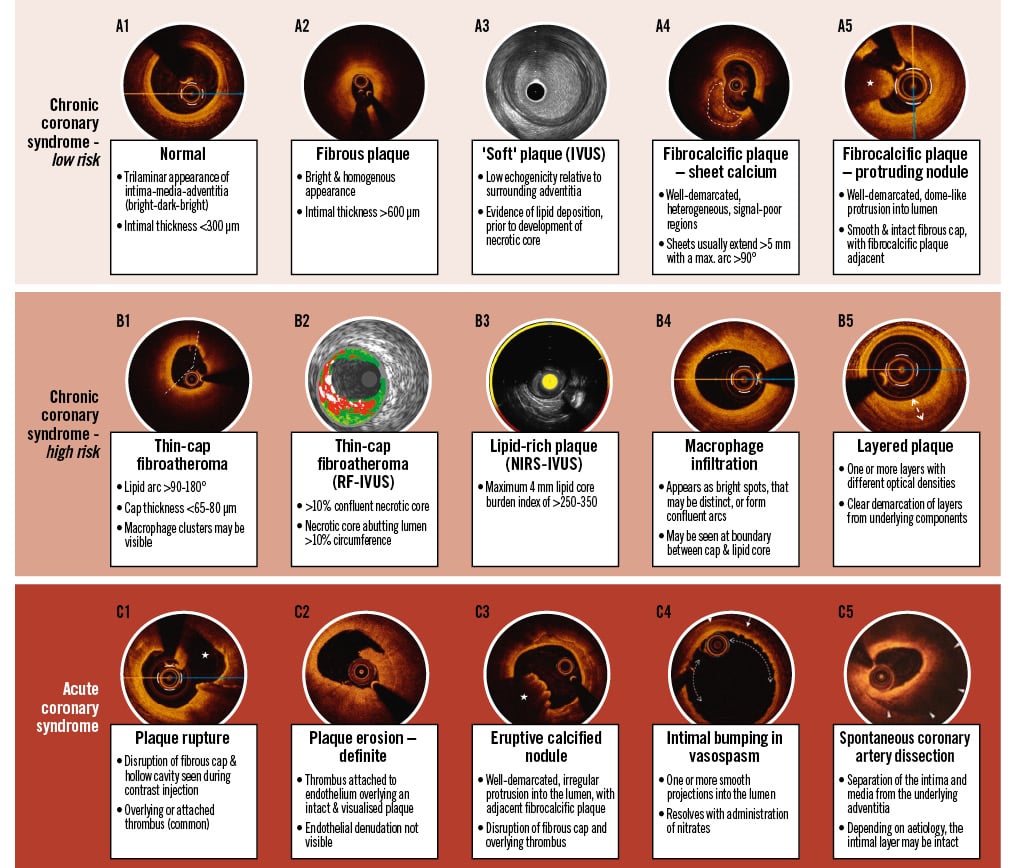

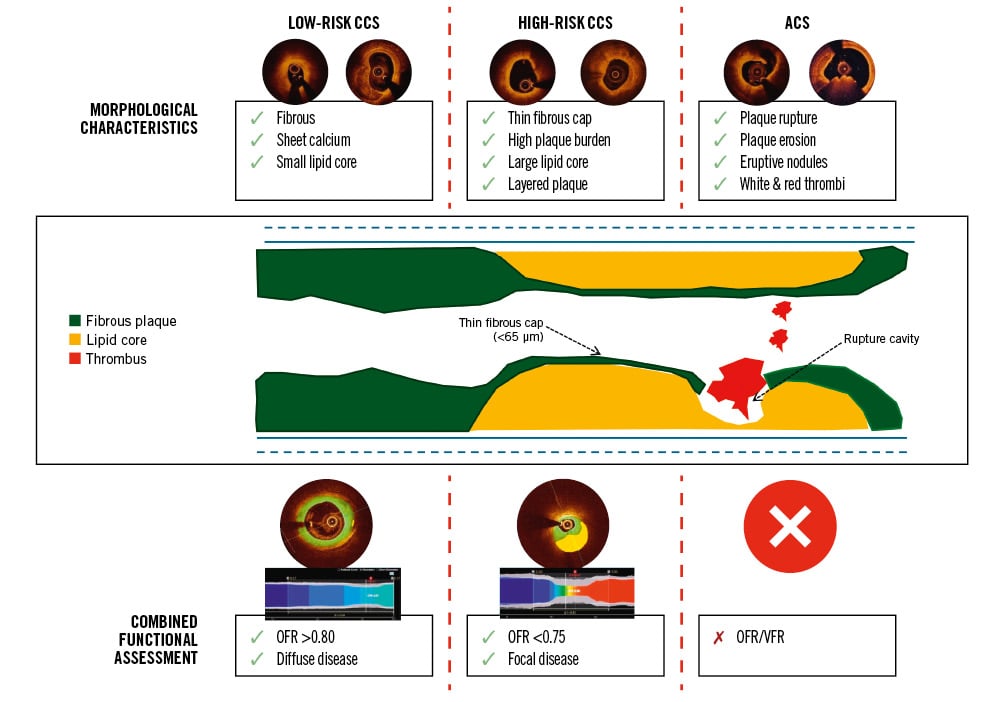

IC imaging enables the morphological assessment of plaque characteristics in vivo. These technologies have supported an evolution in our understanding of coronary atherosclerosis that may be reliably applied to guide clinical diagnosis, inform lesion stratification, and facilitate procedural planning (Central illustration). Plaque may be categorised as lipid-rich, fibrous, and calcific, with each morphology associated with stereotyped biomechanical properties – in vivo, multiple morphologies may coexist within a single lesion, and their relative distribution is an important consideration for interventional strategy planning.

Central illustration. Lesion characteristics stratified according to associated clinical risk & syndrome. Reproduced with permission from37109110. IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; NIRS: near-infrared spectroscopy; RF: radiofrequency

Morphological characteristics & PCI strategy

Clinically significant calcification is present in approximately 20% of patients undergoing PCI and is associated with adverse clinical outcomes18. Vascular calcification impacts the delivery of angioplasty equipment, resists balloon expansion, and results in radial constraint of stents. IC imaging detects calcified plaque with high sensitivity and specificity, and its application in guiding PCI in calcified lesions is associated with increased post-PCI minimum stent area (MSA)1920. Semiquantitative assessment of calcium volume with OCT or IVUS, integrating assessment of calcium arc, depth, length, or morphology, may predict the risk of stent underexpansion (Supplementary Table 1)212223 and is increasingly integrated into treatment algorithms to guide early escalation to advanced calcium modification techniques18.

Nodular calcification presents a particular challenge and may be subcategorised into protruding calcified nodules (PCNs) and eruptive calcified nodules (ECNs). PCNs are characterised by a dome-like protrusion into the lumen, with a smooth and intact endothelial layer, whilst ECNs have an irregular surface, endothelial disruption, and overlying fibrin deposition24. Despite the application of dedicated modification protocols, ECNs are associated with significantly increased rates of target vessel failure (irrespective of post-PCI MSA), with reported cases of ECNs recurring through previously stented segments2526.

Lipid-rich lesions, on the other hand, as detected with OCT and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), are associated with increased risks of slow-reflow and periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI), and an IC imaging-guided strategy may favour pharmacological pretreatment and direct stenting2728.

Routine IC imaging assessment of patients with stent failure is essential to understand the underlying mode and mechanism of failure. IVUS can reliably quantify stent underexpansion, but OCT offers superior spatial resolution, enabling more accurate differentiation of thrombus from intimal hyperplasia, assessment of strut endothelialisation, identification of stent fracture, and differentiation of neointimal hyperplasia and neoatherosclerosis29. Several classification systems have been proposed to categorise stent failure and guide treatment according to findings seen on IC imaging (Supplementary Table 2)293031. Whilst application of an IC imaging-guided approach to the management of stent failure is supported by expert consensus and observational data, further prospective trials are needed to confirm the impact of such an approach on clinical outcomes3233.

Culprit lesion identification & tailored therapies in acute syndromes

In acute syndromes, contemporary IC imaging offers the potential to expand our understanding of the substrate, mechanisms, and manifestations of ACS in vivo. The link between plaque characteristics and ACS was initially established from post-mortem histological analysis of patients admitted with acute coronary thrombosis24. Fibroatheromas are plaques with a large lipid core and are categorised as thin- or thick-cap according to the thickness of the overlying fibrous cap. In histological study, a cap thickness less than 65 μm is present in 95% of cases of plaque rupture (PR), and an inflammatory infiltrate is abundant in all cases of PR-associated thrombosis24. Whilst PR accounts for approximately half of ACS events, purely fibrous lesions may manifest as acute thrombosis due to plaque erosion (PE) with smooth muscle and endothelial cell loss at susceptible points in a plaque. Although the mechanism of this endothelial denudation remains unclear, PE is responsible for 30-40% of ACS24. This proportion appears to be increasing in the context of contemporary preventative therapy and mirrors a shifting prevalence of non-ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI) relative to ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) in ACS presentation5. Lesions composed of dense collagen and sheet calcification (described as “fibrocalcific”) are rarely associated with acute thrombosis, with ECNs causing fewer than 5% of acute events24.

OCT permits characterisation of the underlying substrates of ACS due to atherosclerosis, the underlying mechanisms including PR and PE, and subsequent manifestations, such as white and red thrombi, with significantly greater sensitivity and reproducibility than IVUS34. OCT is therefore preferred for the assessment of patients admitted with ACS, particularly where the culprit lesion remains ambiguous despite coronary angiography16. One in five patients admitted with suspected MI have non-obstructed coronary arteries; using clinical, angiographic, and physiological criteria to identify the culprit lesion can result in inappropriate PCI in 25% of such patients3536. OCT assessment enables identification of a culprit lesion in up to 50% of those with MI with non-obstructive coronary arteries, providing invaluable data to inform therapeutic decision-making37.

OCT may identify other key diagnostic findings to guide management of patients following an acute presentation. Intimal bumping, representing folds in the intimal layer, is a pathognomonic finding of ACS secondary to coronary spasm (Central illustration C4)37. When spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is suspected despite equivocal angiographic findings, intracoronary imaging may resolve diagnostic uncertainty, whilst acknowledging risks associated with instrumentation16. Expert opinion states that OCT may offer superior ability to discriminate SCAD from important differentials such as lipid-rich plaque (Central illustration C5)38. However, in one retrospective series of 63 patients with suspected SCAD assessed with OCT, complications were noted in five patients, including two cases of false lumen propagation39. In cases of suspected ACS secondary to microvascular or embolic aetiology, OCT facilitates the identification of a healthy, trilaminar vessel, increasing confidence in the diagnosis to guide further management.

Integrating a routine assessment of culprit lesions with high-resolution IC imaging may herald a new era of therapies tailored specifically to culprit lesion characteristics5. In the proof-of-concept EROSION study, a single-arm trial of 55 patients, a strategy of a purely antithrombotic treatment without PCI for OCT-adjudicated PE was associated with an acceptable major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) rate of 7.5% at 1 year – whilst minimum lumen area (MLA) was unchanged, and nearly half of patients had no residual thrombus on 12-month OCT assessment40. EROSION III was a multicentre RCT of 246 patients with STEMI and restoration of flow, following vessel wiring or aspiration thrombectomy. Patients were randomised to OCT-guided or angiography-guided therapy. In the OCT-guided arm, two-thirds of patients had an underlying PR, whilst one-quarter had a PE. The investigators demonstrated that a physician-led strategy of OCT guidance was associated with less stent implantation (43.8% vs 58.8%; p=0.024) and equal MACE at 1 year (1.8% vs 2.6%; p=0.67) compared with an angiography-guided strategy41. Ongoing research in this area has the potential to shift ACS treatment to a mechanism-mediated approach, with routine characterisation of culprit arteries with IC imaging offering the potential to drive an important therapeutic shift.

Plaque composition, prognosis & automated lesion stratification

To date, IC imaging has been predominantly deployed as a tool for PCI planning and optimisation. This approach may limit the potential offered by IC imaging to refine lesion stratification, guide novel therapeutic approaches, and refine revascularisation decision-making.

Plaque morphological characteristics & risk of future events

IC imaging technologies have supported an evolution in our understanding of coronary atherosclerosis that may be reliably applied to inform lesion stratification and guide clinical care. Histological study established that a thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA), with evidence of cholesterol crystal deposition, a large necrotic core, neovascularisation, and immune cell infiltration, represents the highest clinical risk lesion and is commonly referred to as a “vulnerable” plaque424.

Several IC imaging-based longitudinal cohort studies have confirmed these findings in vivo (Supplementary Table 3)4243444546474849505152. In patients assessed with IVUS, a high plaque burden (>70%) is the strongest predictor of MACE, whilst an MLA ≤4.0 mm2 and the presence of radiofrequency (RF)-IVUS-defined TCFA (Central illustration B2) are independent predictors of future MACE42. RF-IVUS applies spectral analysis to the IVUS backscatter signal to improve soft-tissue discrimination but does not significantly enhance the ability to identify lipid53.

The addition of NIRS to IVUS can resolve this shortcoming. NIRS employs light in the infrared spectrum, at wavelengths of 700-1,000 nm, using a laser and sensor mounted on the imaging catheter to assess plaque composition and identify lipid with high precision54. The results are presented on a chemogram that maps the probability of a lipid core plaque onto a colour-coded graphical representation of the arterial wall, with yellow areas representing a>0.98 probability of the presence of lipid (Central illustration B3). A numerical output termed the lipid core burden index (LCBI) is generated and, in the LRP study, an elevated maximum LCBI in any 4 mm segment of the scanned vessel (maxLCBI4mm [i.e., greater than 400]) carried a lesion-specific hazard ratio (HR) of 3.39 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.85-6.20)46. PROSPECT II demonstrated that a high plaque burden and large lipid core (i.e., plaque burden ≥70% and maxLCBI4mm ≥324.7) had a 4-year lesion-level MACE rate of 7.0%, compared with 0.2% when neither feature was present47. The combination of high-resolution IVUS with automated assessment of plaque lipid content enables identification of high-risk lesions in a manner that is both accessible and intuitive.

OCT can identify high-risk characteristics of vulnerable plaque with the greatest precision55. The CLIMA registry, of non-flow-limiting lesions in the left anterior descending artery (LAD), demonstrated that when each of the four cardinal features of high-risk plaque were present (i.e., MLA <3.5 mm2, fibrous cap thickness <75 μm, lipid arc >180°, and OCT-defined macrophages), adverse events were predicted with an HR of 7.54 at 1 year (95% CI: 3.1-18.6)48. In the COMBINE OCT-FFR study, the presence of a TCFA in diabetic patients with non-flow-limiting lesions was associated with an almost 5-fold increase in the risk of cardiac death, target vessel MI, target lesion revascularisation, or hospitalisation with angina at 18 months (HR 4.65, 95% CI: 1.99-10.89)49. Following acute MI, non-culprit lesions with an MLA <3.5 mm2 and a thin fibrous cap predicted an increased risk of MACE at 4 years, with an HR of 5.23 (95% CI: 2.98-9.17)51.

Histological analysis and subsequent IC imaging studies in vivo suggest that many patients experience PR or PE events that are clinically silent, with acute thrombus formation followed by flow restoration and spontaneous healing. This subclinical process is associated with unstable syndromes and increased systemic risk56. Layered or healed coronary plaque may be best appreciated in vivo with OCT (Central illustration B5) and is associated with rapidly progressive lesions, multivessel disease, and increased atheroma burden57. In the COMBINE-OCT cohort, after TCFA, layered plaque was the strongest predictor of future adverse events58. It is likely that, as our understanding of vascular biology improves, the natural history of layered plaque, its role in plaque destabilisation and as a marker of underlying clinical risk will become more apparent.

The morphofunctional assessment – a novel approach to invasive lesion assessment

Important barriers to widespread adoption of IC imaging, particularly for advanced lesion stratification and ACS culprit identification, include challenges with image interpretation, duration of image analysis in routine practice, and reproducibility between operators6. Applying AI techniques to IC imaging interpretation has the potential to address many of these concerns, with novel technologies enabling automated image segmentation and three-dimensional computational reconstruction, from which lumen contours, arterial dimensions, and atherosclerotic plaque composition can be modelled59. Such models are increasingly integrated into proprietary vendor-provided and dedicated bespoke software for both IVUS and OCT5960616263.

Automated plaque analysis

Automated plaque characterisation has evolved in complexity and performance with expansion in AI techniques and computational power. Early iterations focused on identification and quantification of calcium, with a discriminatory accuracy of 0.91-0.99 in published datasets64. Calcium detection algorithms are now integrated into commercially available software but lack prospective clinical validation. Algorithms for identification of fibrous and lipid-rich plaque demonstrate high degrees of accuracy in derivation and external validation cohorts but require further validation prior to integration into routine practice. Lipid-rich plaque may be further characterised with assessment of fibrous cap thickness, lipid angle, cholesterol crystal and macrophage infiltration within 25 seconds of image acquisition59656667. We may now be approaching an era where identification of high-risk or vulnerable plaque can be performed in routine care to improve lesion stratification and direct therapy.

In acute syndromes, whilst plaque rupture can often be readily identified, plaque erosion is a diagnosis of exclusion in vivo, as even OCT lacks the requisite spatial resolution (Central illustration C1, C2). Recently described deep-learning (DL) algorithms enable identification and quantification of luminal thrombus68 and enhance diagnosis of plaque erosion so that even inexperienced operators may operate at the level of an expert clinician69. Whilst an exciting demonstration of the potential of AI, these models remain in an early stage of development.

Imaging-derived fractional flow reserve

In patients with CCS undergoing invasive angiography, international guidelines currently recommend with a Class I, Level of Evidence A recommendation that intermediate stenoses should undergo invasive functional stratification using fractional flow reserve (FFR) or the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR)2. In the FAME study, revascularisation guided by FFR enabled safe deferral of PCI, with reductions in death, non-fatal MI, and revascularisation at 1 year70. FAME II showed that in “functionally significant” lesions, pressure-wire guided PCI was associated with a reduction in urgent symptom-guided revascularisation but no difference in prognostically relevant events such as spontaneous MI or death71. The magnitude of abnormality on FFR/iFR is associated with the burden of “typical” or “Rose” angina72, whilst a higher pullback pressure gradient (PPG; i.e.,>0.66) identifies focal lesions where PCI is most likely to deliver a symptomatic benefit73.

A lesion’s functional behaviour is intrinsically linked to its morphological characteristics. Lipid-rich plaque, as assessed by RF-IVUS, is correlated with a reduced FFR, with a concomitant reduction in FFR as the size of the necrotic core increases74. Focal lesions with an FFR <0.80 and a raised PPG demonstrate increased plaque volume, a large lipid burden, and a higher prevalence of TCFA than diffuse lesions75 (Figure 1).

Automated image interpretation using AI, paired with advances in fluid dynamic modelling, may now combine these two concepts and enable a comprehensive morphofunctional assessment using a single IC imaging device. This has the potential to transform cardiac catheterisation laboratory workflows and render the functional versus morphological dichotomy redundant76. Automated lumen contouring permits the generation of a physiological model from which “functional” significance may be predicted. IVUS- and OCT-derived FFR models have been reported, with both demonstrating good correlation with wire-based FFR. Such calculations are increasingly performed in under 1 minute, sufficient to guide real-time clinical decision-making. OCT-based FFR (OFR) combines a model of virtual hyperaemic flow velocity with automated lumen contouring to generate an OFR pullback, with the distal value corresponding to invasive FFR. Computation can be performed in 55 seconds on a standard laptop after importing OCT digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) images and identified physiologically significant stenoses (i.e., wire-based FFR ≤0.80) with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.87-0.97). Performance was similar in LAD and non-LAD lesions and outperformed the optimal MLA threshold (1.89 mm2), which had an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.72-0.86)77. Virtual flow reserve (VFR) uses an alternative, lumped-parameter model based on OCT-derived lumen geometry to estimate functional significance. Rather than estimating coronary flow or microvascular function, VFR is based on model-derived pressure losses to produce an estimate of wire-based FFR. This can be computed during OCT acquisition, adding less than 1 second. In a validation study, this showed good correlation with wire-based FFR, predicting flow-limiting stenoses with an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI: 0.84-0.92)78.

Figure 1. Morphofunctional lesion stratification with AI-enabled intracoronary imaging. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AI: artificial intelligence; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; OFR: optical coherence tomography-based fractional flow reserve; VFR: virtual flow reserve

Post-PCI assessment

IC imaging vendor software now provides measures of absolute and relative stent expansion that are increasingly complex but superior to conventional measures – the volumetric stent expansion index, for example, significantly outperforms MSA as a predictor of future events79. The application of a combined morphofunctional assessment may identify patients with a well-expanded stent and an optimal functional result, free of post-PCI complications. Such patients may benefit from early de-escalation of antianginal and dual antiplatelet therapies (DAPT). Conversely, early identification of those at greatest risk of target vessel failure may guide physicians towards escalated preventative therapy and extended DAPT80. We are on the cusp of an era where we can characterise the heterogeneity of atherosclerotic plaque, its functional and anatomical profile, and the success of PCI, all with IC imaging and AI-enabled software81. Whilst highly promising, these technologies remain expensive, and recent data assessing the accuracy of angiography-derived functional assessment highlight the importance of prospective clinical validation prior to widespread application82.

Preventative therapy for high-risk plaque

The association between lesion morphological features and clinical outcome has focused attention on targeted therapies to ameliorate risk. Treatment strategies may be categorised as mechanical, systemic pharmacological therapy or local therapy to promote plaque pacification (Table 2)418384858687888990.

Table 2. Targeted therapies for patients with high-risk lesions as assessed with intracoronary imaging.

| Study | Cohort | Comparison | Primary endpoint | Results | High-risk lesion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC imaging-guided local therapy for high-risk plaque | |||||

| PREVENT (2024)83 | 1,606 patients CCS & non-culprit ACS Non-flow-limiting lesions (FFR >0.80) High-risk lesion as per IC imaging criteria | Medical therapy vs PCI with DES or BVS 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Composite of cardiac death, target vessel MI, ischaemia-driven TVR, or hospitalisation with progressive or unstable angina | Primary endpoint: 3.4% OMT vs 0.4% PCI at 2 yrs (p=0.0003) 33% of patients in PCI arm treated with BVS 100% of PCI were optimised using IC imaging | At least 2 of the following: MLA <4.0 mm2 by IVUS or <3.5 mm2 by OCT Plaque burden >70% (by IVUS) TCFA (according to RF-IVUS* or OCT criteria#) Lipid-rich plaque (maxLCBI4mm >315) |

| DEBuT-LRP (2024)84 | 20 patients Non-culprit lesions in NSTE-ACS Non-flow-limiting with lipid-rich plaque | Baseline vs 9-month follow-up maxLCBI4mm following treatment with paclitaxel DCB | Primary endpoint: Change in maxLCBI4mm from baseline | Primary endpoint: Baseline maxLCBI4mm 397 (IQR 299-597) vs 9-month maxLCBI4mm 211 (IQR 106-349) (p<0.001) | Lipid-rich plaque, as assessed by NIRS-IVUS: Any lesion with maxLCBI4mm >325 |

| PROSPECT ABSORB (2020)85 | 182 patients Non-culprit lesions in ACS Non-flow-limiting lesions (FFR >0.80, iFR >0.89) Plaque burden ≥65%, as assessed by IVUS Suitable for BVS | Medical therapy vs PCI with BVS 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Minimum lumen area on follow-up IVUS Secondary safety endpoint: Composite of cardiac death, target vessel MI, or clinically driven TLR | Primary endpoint: 3.0±1.0 mm2 OMT vs 6.9±2.6 mm2 BVS at 2 yrs (p≤0.0001) Secondary safety endpoint: 4.5% OMT vs 4.3% BVS at 2 yrs | As assessed by NIRS-IVUS: Plaque burden ≥70% MLA ≤4.0 mm2 MaxLCBI4mm ≥324.7 95% of lesions had ≥1 high-risk characteristic 74% of lesions had ≥2 high-risk characteristics 43% had all 3 high-risk characteristics |

| PECTUS (2020)86 | 34 patients (planned for 500 but terminated early) Non-culprit lesions in ACS Non-flow-limiting lesions (FFR ≥0.80) OCT-defined vulnerable plaque suitable for BVS | Medical therapy vs PCI with BVS 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal MI, and unplanned TVR | Primary endpoint: 1 event OMT vs 3 events BVS at 2 years | Any 2 of the following (as assessed by OCT): Lipid arc >90° Cap thickness <65 µm OCT-defined cap rupture or thrombus formation |

| FORZA (2020)87 | 350 patients CCS & non-culprit lesions in ACS Angiographically intermediate stenosis (30-80%) | FFR-guided PCI with DES vs OCT-guided PCI with DES 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Composite of death, MI, target vessel revascularisation and significant residual angina (SAQ <90) | Primary endpoint: 14.8% FFR guidance vs 8.0% OCT guidance (p=0.048) 32% of FFR arm treated with PCI vs 53% of OCT arm | One of the following (as assessed by OCT): Area stenosis ≥75% Area stenosis >50% but <75% and MLA <2.5 mm2 Area stenosis >50% but <75% and plaque rupture |

| EROSION III (2022)41 | 246 patients STEMI & TIMI III flow and <70% residual stenosis after wiring +/− thrombectomy Conservative stenting strategy with DES placement in high-risk lesions only | Angiography-guided primary PCI vs OCT-guided primary PCI 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Rate of DES placement Primary safety endpoint: Composite of cardiac death, recurrent MI, TLR, and hospitalisation with unstable angina at 1 month Secondary safety endpoint: Composite of cardiac death, recurrent MI, TLR, and hospitalisation with unstable angina at 1 year | Primary endpoint: 44.8% DES placement with angio-guided PCI vs 58.8% with OCT guidance (p=0.032) Primary safety endpoint: 3 events with angio guidance vs 2 events with OCT guidance at 1 month (p=0.67) Secondary safety endpoint: 10 events with angio guidance vs 11 events with OCT guidance |

High-risk ACS lesion (as assessed by OCT): Plaque rupture with dissection and/or haematoma Conservative stenting strategy advised if OCT-defined ACS mechanism was: Plaque erosion Plaque rupture without dissection and/or haematoma Spontaneous coronary artery dissection |

| IC imaging-guided systemic therapy for high-risk plaque | |||||

| COLOCT (2024)88 | 128 patients Non-culprit lesions in ACS Angiographically intermediate stenosis (30-70%) OCT-defined lipid-rich plaque | Placebo vs 0.5 mg colchicine daily 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Change in minimal fibrous cap thickness at 1 year Secondary safety endpoint: Composite of all-cause death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, and ischaemia-driven revascularisation at 1 year | Primary endpoint: +51.9 µm (IQR 32.8-71.0) with placebo vs +87.2 µm (IQR 69.9-104.5) with colchicine (p=0.006) Secondary safety endpoint: 17.3% of participants with placebo vs 11.5% with colchicine (p=0.402) | Lipid-rich plaque, as assessed by OCT: Lipid arc >90° |

| COCOMO-ACS (2024)89 | 64 patients Non-culprit lesions in NSTE-ACS Angiographically intermediate stenosis (20-50%) OCT-defined lipid-rich plaque | Placebo vs 0.5 mg colchicine daily 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Change in minimal fibrous cap thickness at 12-18-month follow-up Secondary safety endpoint: Composite of death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke or TIA, repeat revascularisation, or unplanned hospitalisation 12-18-month follow-up | Primary endpoint: +29.4±19.7 µm with placebo vs +39.0±20.3 µm with colchicine (p=0.08) Secondary safety endpoint: 10 events with placebo vs 7 events with colchicine | Lipid-rich plaque, as assessed by OCT: Lipid arc >90° Fibrous cap thickness ≤120 µm |

| YELLOW III (2023)90 | 110 patients CCS patients Angiographically intermediate stenosis (30-50%) OCT features of lipid-rich plaque | Baseline vs 6-month follow-up fibrous cap thickness and maxLCBI4mm following treatment with evolocumab | Co-primary endpoint: Change in minimal fibrous cap thickness & maxLCBI4mm at 6-month follow-up | Co-primary endpoint: Fibrous cap thickness: Baseline 70.9±21.7 µm vs 6-month 97.7±31.1 µm (p<0.001) MaxLCBI4mm: Baseline 306.8±177.6 vs 6-month 213.1±168.0 (p<0.001) | OCT-defined lipid-rich plaque requires: Lipid arc >90° Fibrous cap thickness ≤120 µm |

| INTERCLIMA (NCT05027984) | 1,420 patients (estimated) Non-culprit lesions in ACS Angiographically intermediate lesion (40-70% stenosis) | FFR/iFR-guided PCI vs OCT-guided PCI Perform OCT-guided PCI if features of vulnerable plaque | Primary endpoint: Composite of cardiac death or non-fatal target vessel MI | Awaited 2025 | OCT-defined vulnerable plaque requires fibrous cap thickness <75 µm and 2 of the following: MLA <3.5 mm2 Lipid arc >180° Macrophage infiltration |

| COMBINE-INTERVENE (NCT05333068) | 1,222 patients (estimated), with de novo multivessel disease (i.e., ≥2 de novo lesions in 2 native arteries) ACS or CCS presentation Eligible lesions may be culprit ACS lesions, or target lesion with >50% stenosis and TIMI III flow in >2 mm vessel | FFR-guided PCI vs combined FFR-OCT guidance 1:1 randomisation Perform PCI in combined guidance if: FFR ≤0.75 and Vulnerable plaque on OCT | Primary endpoint: Composite of cardiac death, any MI, or any clinically driven revascularisation | Awaited 2026 | OCT-defined vulnerable plaque requires 1 of the following: TCFA (cap thickness ≤75 µm) Ruptured plaque Plaque erosion with 70% area stenosis or MLA <2.5 mm2 |

| VULNERABLE (NCT05599061) | 600 patients (estimated) Non-culprit lesions following STEMI Angiographically intermediate lesion (40-69%) Non-flow-limiting, with FFR >0.80 OCT features of vulnerable plaque | OMT vs OCT-guided PCI of vulnerable plaque 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Composite of cardiovascular death, target vessel MI, clinically or physiologically guided TVR | Awaited 2028 | OCT-defined vulnerable plaque requires all 3 features: Lipid arc >90° for 5 mm length Fibrous cap thickness ≤80 µm OCT-defined plaque burden ≥70% Plaque burden calculated as: [(max.EEM reference area - MLA)/ max.EEM reference area]*100 |

| ESCALATE (NCT06469528) | 50 patients (estimated) CCS patients with hs-CRP ≥2.0 Angiographically intermediate lesions (30-80%) Non-flow-limiting (FFR >0.80) OCT features of high-risk plaque | OMT vs 0.5 mg colchicine daily 1:1 randomisation | Primary endpoint: Change in minimal fibrous cap thickness at 6-month follow-up | Awaited 2027 | OCT-defined high-risk plaque requires: Lipid arc >90° Fibrous cap thickness ≤120 µm |

| *RF-IVUS defined TCFA: ≥10% confluent necrotic core with >30° abutting the lumen in three consecutive frames. #OCT defined TCFA: a lipid plaque with arc >90° and fibrous cap thickness <65 μm. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; BVS: bioabsorbable vascular scaffold; CCS: chronic coronary syndrome; DCB: drug-coated balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; EEM: external elastic membrane; FFR: fractional flow reserve; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IC: intracoronary; iFR: instantaneous wave-free ratio; IQR: interquartile range; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; maxLCBI4mm: maximal lipid core burden indexed in a 4 mm segment; MI: myocardial infarction; MLA: minimum lumen area; NIRS: near-infrared spectroscopy; NSTE-ACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OCT: optical coherence tomography; OMT: optimal medical therapy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; RF: radiofrequency; SAQ: Seattle Angina Questionnaire; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TLR: target lesion revascularisation; TVR: target vessel revascularisation | |||||

Targeted mechanical therapy

The FORZA trial tested a morphology-based stratification against traditional physiological testing. A total of 350 patients with angiographically moderate lesions were randomised to an OCT assessment versus FFR. Patients randomised to the OCT arm (with either chronic or acute coronary syndromes) underwent PCI if there was an area stenosis (AS) ≥75% or if there was an AS ≥50% but <75% and evidence of plaque rupture or MLA <2.5 mm2. At 13 months, the composite outcome of significant angina and all-cause MACE was significantly reduced in the OCT arm87. The FLAVOUR trial applied an IVUS-guided approach, comparing an MLA threshold <3 mm2 (or 3-4 mm2 with a plaque burden >70%), versus FFR-guided revascularisation and demonstrated non-inferiority in terms of MACE at 2 years91. In a blinded post hoc analysis, post-PCI physiological assessment was an independent predictor of target vessel failure at 2 years, with this finding most marked in the IVUS-guided group. This further supports the importance of a combined morphofunctional assessment in PCI optimisation92.

The PREVENT Trial tested a morphology-led approach to lesion stratification in angiographically moderate, non-culprit lesions deemed suitable for medical management (i.e., FFR>0.80). A total of 5,627 patients were assessed with IC imaging, and high-risk features (either by IVUS, RF-IVUS, NIRS-IVUS or OCT criteria) were present in 1,606 individuals who were randomised to IC imaging-guided PCI or optimal medical therapy. At 2 years, there was a 3% absolute reduction in the primary composite outcome, predominantly driven by reductions in hospitalisation with angina and target vessel revascularisation (TVR). The incidence of TVR in the IC imaging-guided PCI arm was just 1.7% at 4 years83. One-third of patients in the intervention arm in PREVENT were treated with bioabsorbable scaffolds, with the results reflecting those of the prematurely terminated PROSPECT ABSORB study85.

There are three ongoing clinical outcome trials testing a morphology-based approach: The VULNERABLE Trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05599061) will randomise 2,500 patients admitted with STEMI and FFR-negative non-culprit lesions with high-risk features on OCT to PCI versus medical therapy; INTERCLIMA (NCT05027984) will test a functional versus morphological assessment with OCT to guide revascularisation decisions in angiographically moderate, non-culprit lesions in patients with ACS; and COMBINE-INTERVENE (NCT05333068) will test a combined assessment with FFR/OCT versus FFR alone in all-comers, regardless of their clinical syndrome, with angiographically moderate lesions. Whilst testing a similar hypothesis, these trials have applied different IC imaging selection criteria, which will be an important consideration (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lesion stratification in clinical trials assessing device-based therapy for high-risk plaque. ACS: acute coronary syndrome; AS: aortic stenosis; FFR: fractional flow reserve; iFR: instantaneous wave-free ratio; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; maxLCBI4mm: maximum lipid core burden index in any 4 mm segment; MLA: minimum lumen area; NIRS: near-infrared spectroscopy; OCT: optical coherence tomography; RF: radiofrequency; TCFA: thin-cap fibroatheroma

Local therapies for plaque stabilisation

Due to concerns related to permanent device placement in preventative intervention and the high number needed to treat in the PREVENT study (i.e., ~150 PCIs to prevent 1 target vessel MI at 2 years), there remains significant interest in alternative locally applied therapy. The DEBuT-LRP pilot study assessed the role of drug-coated balloons (DCBs) for preventative PCI in high-risk lipid-rich lesions, as assessed with NIRS-IVUS. At 9 months, but not at baseline, treatment with paclitaxel DCBs caused significant reductions in lipid-core burden, with no intervention-related complications84. The targeted application of cryotherapy to high-risk lesions promotes lesion stabilisation in preclinical models93, and results from the POLARSTAR first-in-human study are awaited (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05600088). It is likely that there will be an expansion in studies evaluating the role of local therapies for high-risk plaques, where it will be important to show improvement in outcomes when tested against current standard of care.

Pharmacological approaches to high-risk plaque

Coronary atherosclerotic plaque is highly dynamic, and its activity is partly related to the presence and control of established cardiovascular risk factors94. Multiple intracoronary imaging outcome trials have demonstrated the plaque-stabilising effects of lipid-modifying therapies4, with high-intensity statin therapy95 and PCSK9 inhibition being the most intensively studied96. In these large prospective clinical studies, reductions in plasma low-density lipoprotein consistently led to reductions in plaque atheroma volume and plaque lipid content (as measured with LCBI4mm and maximal lipid arc) and increases in fibrous cap thickness – patients who exhibited improvement in all three features (“triple regression”) demonstrated a significant reduction in adverse events at 1 year97.

Multiple randomised clinical trials have established the beneficial effects of anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with recent or historical myocardial infarction98. A single-centre OCT study has provided biological plausibility for these findings, as treatment with colchicine increased fibrous cap thickness whilst reducing maximal lipid arc and macrophage infiltration88. As the armamentarium of disease-modifying therapy expands, stratification with IC imaging has the potential to direct escalated medical therapy to those patients likely to benefit most.

Future directions & novel technologies

Novel prognostic indicators

As AI models for automated lesion assessment develop and evolve, new imaging biomarkers of patient risk will emerge. OCT-derived lipid core burden index is one example of a novel quantitative marker of lesion lipid components that has been validated against NIRS-IVUS99. An OCT-derived maxLCBI4mm >400 predicted increased risks of cardiac death, MI, and target vessel revascularisation with a hazard ratio of 1.87, whilst lesions with a maxLCBI4mm >400 and a thin fibrous cap carried a hazard ratio of 4.87 compared to lesions where neither feature was present100. The lipid-to-cap ratio (LCR) is another novel marker of risk that can be computed simultaneously with a functional assessment with OFR. In a study of 915 non-culprit lesions in patients admitted with ACS, a low OFR and a high LCR predicted 2-year vessel-related MI and revascularisation with a hazard ratio of 15.19 (95% CI: 5.82-39.63), highlighting the potential of this novel and automated morphofunctional approach to stratification101.

Morphofunctional assessment currently relies on models of coronary flow and pressure loss that are derived solely from cross-sectional imaging. A recently described Doppler OCT catheter, however, would enable direct measurement of coronary blood flow in real-time alongside cross-sectional imaging. This offers the potential to enhance the reliability of functional assessment of epicardial stenoses, to integrate microvascular assessment, and to deliver a truly comprehensive assessment to guide lesion stratification102.

Incorporating plaque biomechanics

Alongside plaque anatomical and functional characteristics, assessment of plaque biomechanics may enhance lesion stratification. Low endothelial shear stress has long been acknowledged as a predictor of rapid lesion progression and increased clinical risk, but translation into clinical practice has proved challenging103. These calculations can now be rapidly and reliably performed using AI analysis of IC imaging, though they are not yet available commercially104. This will facilitate assessment of increasingly granular indices of plaque biomechanics, such as endothelial shear stress gradient and plaque structural stress, which are independent markers of risk when assessed alongside established anatomical markers of high-risk plaque and predictors of future or recurrent ACS105.

Multimodality devices & plaque “theranostics”

NIRS-IVUS is the first multimodality device to be introduced to routine clinical practice, but there is now a growing armamentarium of dual or multimodality catheters. The HyperVue Imaging System (SpectraWAVE) pairs “deep” OCT imaging (DeepOCT [SpectraWAVE]) with NIRS lipid detection to enhance detection of the key features of high-risk plaque – DeepOCT enables quantification of plaque burden and fibrous cap thickness, detection of immune cell infiltration, and assessment of lipid core burden with NIRS analysis106. Combining IVUS or OCT with novel light-based imaging modalities allows detailed characterisation of plaque metabolic properties, in addition to morphological characteristics. Intravascular photoacoustic imaging provides assessment of endothelial integrity, macrophage colocation and cell-adhesion molecule expression, whilst catheters that detect near-infrared autofluorescence detect oxidative stress resulting from lipoprotein oxidation and intraplaque haemorrhage107.

Such devices may facilitate the ongoing evolution of IC imaging from a tool used to optimise intervention and refine lesion stratification into a tool to enable delivery of targeted therapy. Near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) molecular imaging requires the infusion of activatable tracers that bind to molecules within metabolically active atherosclerotic plaque and fluoresce when excited with near-infrared light. In a rabbit model of atherosclerosis, a highly inflamed atherosclerotic lesion (characterised by a high NIRF signal) was identified – a NIRF-emitting, photoactivatable agent targeted to macrophages was infused and photoactivated using near-infrared light from the imaging catheter. This resulted in activation of the drug molecule, subsequent attenuation of macrophage activity, resolution of inflammation, and transition from a high-risk lipid-rich plaque to a predominantly fibrous morphology, as assessed by OCT108. This combined “theranostic” approach highlights the central role that IC imaging has potential to play in the assessment, stratification, and treatment of patients with clinically significant coronary atherosclerosis.

Conclusions

IC imaging-guided PCI leads to reductions in target vessel MI, lesion revascularisation, cardiac death, and all-cause death, when compared to angiography-guided interventions, and should now be viewed as the standard of care in patients with high clinical or anatomical complexity. IC imaging has the potential to transform how we understand and manage patients with CAD, offering personalised percutaneous and pharmacological therapies. Routine characterisation of lesion characteristics may be used to improve patient stratification and refine treatment within and beyond the catheterisation laboratory for both chronic and acute coronary syndromes. Automated image interpretation using AI, with integrated morphofunctional assessment, has the potential to democratise expertise and support a step change in interventional cardiology as we move towards targeted application of an ever-larger armamentarium of mechanical and pharmacological interventions.

Funding

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence (Grant no. RE/24/130035). N. Pareek is supported by the Margaret Sail Novel Emerging Technology grant from Heart Research UK (RG2693).

Conflict of interest statement

M. McGarvey: research grant from Abbott. K. De Silva: speaker honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Philips, and Shockwave Medical. T.R. Keeble: advisory board member and research grants with Abbott and Philips; and speaker fees from Nipro. T.W. Johnson: institutional research grants from Abbott; and consultancy/speaker fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, and Terumo. P. O’Kane: speaker fees from Abbott. Z.A. Ali: institutional grant support from Abbott, Abiomed, ACIST Medical, Amgen, Boston Scientific, CathWorks, Canon, Conavi, HeartFlow, Inari Medical, Medtronic, National Institute of Health, Nipro, Opsens Medical, Medis, Philips, Shockwave Medical, Siemens, SpectraWAVE, and Teleflex; consulting fees from Abiomed, AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, CathWorks, Opsens Medical, Philips, and Shockwave Medical; and equity in Elucid, Lifelink, SpectraWAVE, Shockwave Medical, and VitalConnect. S. Tu: co-founder of Pulse Medical; research grants and consultancy from Pulse Medical. J.M. Hill: speaker honoraria and institutional grants from Abbott, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, and Shockwave Medical; has received equity from Shockwave Medical; and consultancy fees from SpectraWAVE. R. Dworakowski: speaker honoraria and proctor fees from Abbott. N. Pareek: honoraria and educational grants from Abbott Vascular, honoraria from NIPRO; and serves on the Advisory Boards for Boston Scientific and Johnson & Johnson. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.