Abstract

The safety of drug-eluting stents (DES) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention has been questioned in several independent meta-analyses (i.e., systematic reviews of primary research studies employing statistical methods to provide pooled estimates) published or presented at the end of 2006. Other reviews and meta-analyses have followed in the beginning of 2007, albeit with unclear or conflicting results. This article provides a succinct perspective and critical appraisal of recently published meta-analyses focusing on DES safety, summarising key features and findings of each work, and recommending avenues for further research and practice.

Introduction

The occurrence of several duplicate meta-analyses focusing on the same clinical topic, and reaching sometimes frankly disparate conclusions, is not a surprise for researchers with a specific interest in systematic reviews or meta-analyses, as well as evidence-based medicine.1 This issue has however gained much larger and clinical implications with the recent publication of a plethora of meta-analyses focusing on the long-term safety of intracoronary drug-eluting stents (DES). Interestingly, two meta-analyses presented at the 2006 World Congress of Cardiology,2-3 both suggesting a potential late hazard with DES, have been followed by as many as other eight overlapping works published in peer-reviewed journals in less than seven months.4-11

We hereby provide a succinct and critical appraisal of recently published meta-analyses focusing on DES safety, summarising key features and findings of each work, and recommending avenues for further research.

Clinical and research context

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a mainstay in the management of patients with coronary disease. Since its beginning as a balloon-only intervention, PCI was revolutionised by the introduction of bare-metal stents.12 While addressing many of the drawbacks of balloon-only PCI (e.g., abrupt closure), standard stents are fraught by a significant risk of late failure due to neointimal hyperplasia and ensuing restenosis, especially in small vessels and long-lesions.13 The most recent development of DES has enabled us to address the problem of neointimal hyperplasia, without sacrificing the mechanical properties of the metallic platform.

Despite several promising data limited to short term follow-up14 or low risk patients,15 since 2004 a number of reports were published suggesting a potential for late adverse events with DES.16-17 Thus, it was only a matter of time before investigators with expertise in systematic reviewing processes and meta-analytic pooling would exploit the superior statistical power of these approaches to unmask the long-term increase in the risk of thrombotic events with DES.

Further contributions to this research topic have been recently provided by the consensus Academic Research Consortium (ARC) definitions of definite, probable, or possible stent thrombosis.18 However, even in the ARC context there is still a risk of underestimating thrombotic events if adjudication is based only on angiography or pathology, and conversely, overestimating thrombosis rates if myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death are considered as a proxy for stent thrombosis.

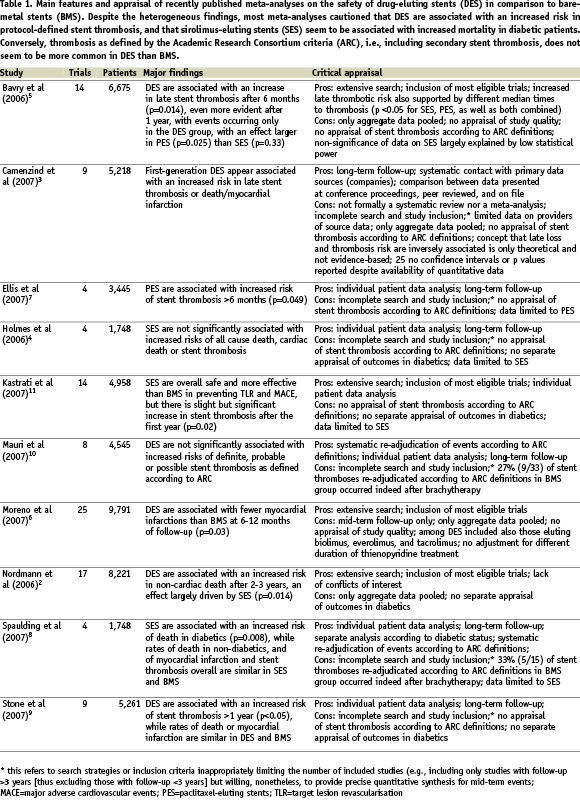

While there is little debate that DES increase in a statistically significant fashion the risk of protocol-defined stent thrombosis after dual antiplatelet discontinuation, the most important question is whether this risk is magnified as much as to become clinically relevant. We leave such a topic open to the discussion and informed decision of the reader, as this was indeed the main focus of all the meta-analyses recently published on DES, whose findings on the risk of stent thrombosis, as well as of other events, are summarised in Table 1.

Critical appraisal of available meta-analyses

Keeping in mind the guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration,19 the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) statement,20 and the Oxman-Guyatt index,1 we recognised a number of limitations in the available DES meta-analyses. Indeed, a pivotal distinction should be made between meta-analyses based only on published and/or aggregate data, and thus limited in their ability to correct for incomplete or inaccurate data, and meta-analyses using data gathered at the patient or lesion level, in which all data sets from individual studies are pooled into a single data set, enhancing coherence and quality, and enabling sophisticated subgroup or multivariable analyses.21 Conversely, the latter type of works is most often limited by a smaller number of studies, thus potentially increasing the risk of small study (e.g., publication) bias.

Appraisal of recent meta-analyses on DES thus showed, as is commonplace in meta-analytic practice, that individual patient data analyses4,7-11 were often limited by incomplete study search and inclusion (thus increasing the risk of small study bias), despite being more internally valid than study level analyses,2,5-6 thanks to thorough event adjudication, data checking and time-to-event analysis. Another work, despite being originally proposed as a meta-analysis, was recently published as a systematic review, including raw quantitative data, but failing to present conventionally pooled data.3 The reasons for refraining from meta-analytic pooling in this case were not reported.

In addition, most works limited their adjudication of stent thrombosis to the protocol definition, which often proves different from study to study, and usually underestimates the real occurrence of this event. Only two of the meta-analyses systematically employed the recently developed ARC definitions of stent thrombosis, thus providing more informative data on its occurrence.8,10 On the other hand, the ARC criteria now include as well thrombotic events occurring after repeated treatment for restenosis (“secondary stent thrombosis”). This may be appropriate if repeat intervention is performed with balloons or stents. Conversely, including events that occur after a well known pro-thrombotic therapy such as brachytherapy may be misleading.8,10

Finally, only one of the works was published by investigators without any evident financial or funding interest in DES,2 as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration and others.19,22

Synthesis and recommendations

First, we should remember that no clinical trial to date was adequately powered for the appraisal of stent thrombosis, and in no case was this event the primary end-point. Thus, all speculations have been based on secondary and/or post-hoc analyses. Nominally statistical significant findings (p <0.05) were indeed found in some, but not all analyses, raising the issue of alpha error (the risk of false positive statistical tests due to the performance of many comparisons and sub-analyses). Similarly, no study to date was adequately powered (i.e., with a sample size sufficiently large to minimise beta error [the risk false negative findings]) to be able to confirm or disprove, in a precise and accurate fashion, whether DES are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis. This fact is also a clear reminder that statistical significance stemming from underpowered trials may not translate into clinically significant findings.

Most meta-analyses cautioned that DES are associated with an increased risk in protocol-defined stent thrombosis, and that sirolimus-eluting stents (SES) seem to be associated with increased mortality in diabetic patients. Conversely, ARC-defined thrombosis does not seem to be more common in DES than BMS. However, the ARC decision to include secondary stent thromboses (i.e., those occurring after repeat intervention, even brachytherapy), while correct according to the intention-to-treat principle, remains open to discussion and can be misleading in a setting where the primary goal is to understand the pathophysiological substrate of a potentially ominous event such as very late stent thrombosis.

Several practical actions can be recommended, and to this end we borrow recommendations from other colleagues to individualise patient management, including indications to percutaneous revascularisation vs surgery or medical therapy only, as well as indications toward a specific coronary device.23

In addition, and focusing more on the evident discrepancies or redundancies in the current DES literature, we would like to stress that in the future the following should be addressed:

– A more thorough comparison of per-protocol and ARC-defined stent thrombosis events, which includes reasons for discrepancies;

– A more thorough appraisal of the risks and benefits of DES (especially with SES) in diabetic vs non-diabetic patients;

– Strive for a unique, unanimous, collaborative, cumulative, prospectively planned and designed systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis on DES similar to the one produced by the Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration.24

Acknowledgements

This work is part of an ongoing senior investigator program of the Centre for Overview, Meta-analysis, and Evidence-based medicine Training (COMET) based in Turin, Italy (http://www.comet.gs).